By D. Dominick Lombardi

Front window installation view, Jeanne Jaffe: Becoming Hybrid and Emilio Martinez: Freedom From Fear, L’Space Gallery. Courtesy of L’Space Gallery.

The pairing of the work of Jeanne Jaffe with that of Emilio Martinez is a brilliant one. Both artists focus on conditions and limitations related to fallibility, hope, tolerance, and subtle tinges of humor; however, the works they produce are technically and aesthetically quite different.

Jaffe, a wizard of invention, dazzles us across a spectrum of genres: from finely glazed ceramic characters and moving narratives woven in cotton or drawn on paper, to stunning biomorphic sculptures in bronze, resin, and fiberglass, as well as an unsettling video and trippy animations. What emerges is a private universe in which the interplay of randomness and redemption is astonishing.

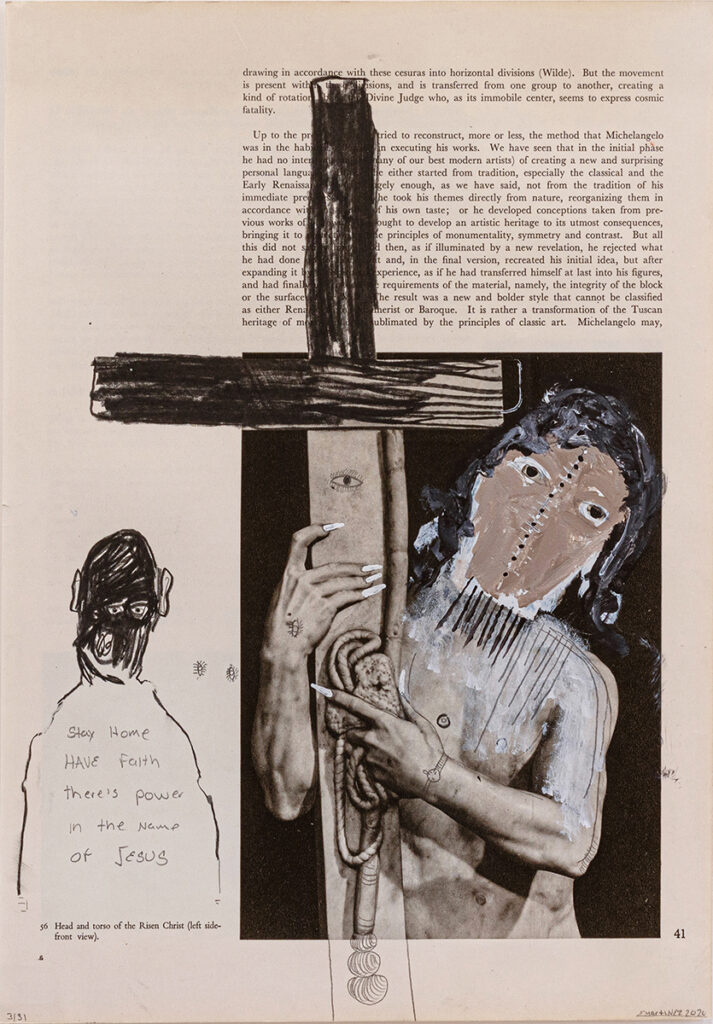

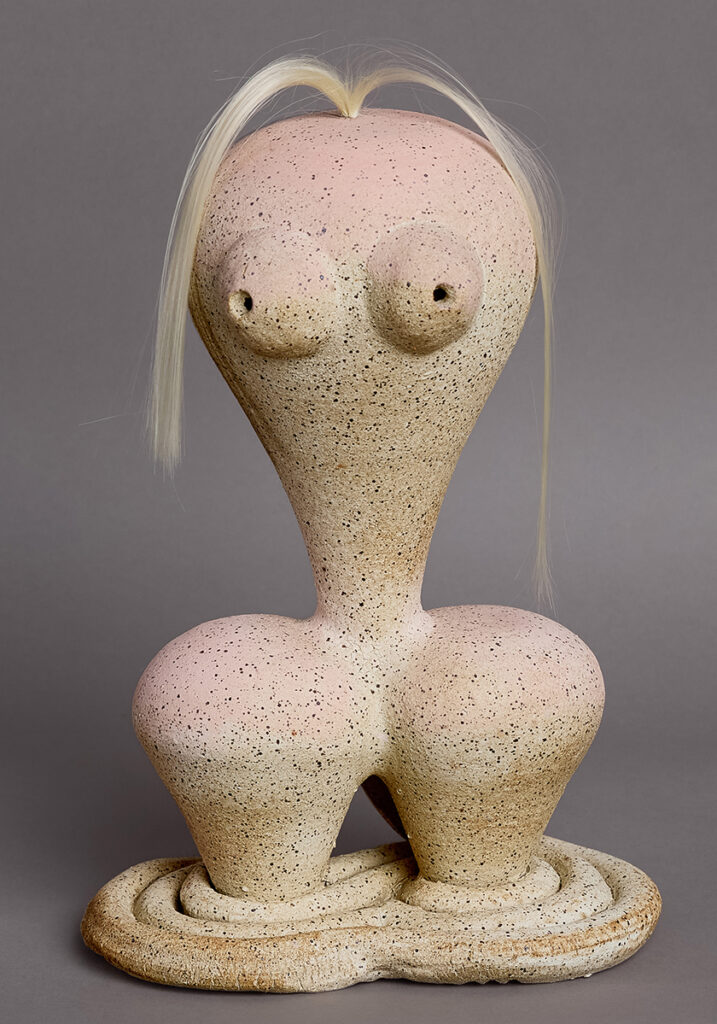

Left, Emilio Martinez, Modern Jesus, 2025. Acrylic paint, charcoal, and graphite on art history book page, 10.5 × 14.5 in. Right, Jeanne Jaffe, Spinal Tap, 2025. Glazed ceramic and synthetic hair, 25 × 11 × 6 in. Images, Courtesy of L’Space Gallery.

My first reaction to Jaffe’s work is one of cautious enchantment. Despite the humor present in many of the fluid forms and material combinations, there is an undercurrent of hidden foreboding. This unsettling presence becomes abundantly clear in the lower gallery, where Alice in Dystopia (2024) is featured. This 7:05-minute video, created using stop motion, rapid edits, and puppetry—reimagines the characters from Lewis Carroll’s classic tale as they confront a dominant and destructive police state. Seeing Wonderland reduced to smoldering ruin, one cannot help but draw parallels to today’s political climate, where an alarming “might makes right” mentality leads to the needless destruction of lives, families, and fundamental moral codes.

Returning to the main level of the gallery, a sense of hope resurfaces in Jaffe’s work through fantastical forms marked by virtuosic technique and eccentric contours. Her intention to engage viewers on a deep, visceral level is deliberate, as she explores what she describes as a “pre-verbal state of being”—a time prior to instructive language and the prejudgments it imposes. This conceptual space affords the artist remarkable freedom to engage all cultures as a single, continuous entity, resulting in a timeless and otherworldly atmosphere.

Jeanne Jaffe, Old Man, 2025. Glazed ceramic and synthetic hair, 13 × 8 × 8 in. Courtesy of L’Space Gallery.

One of my favorite works, Old Man (2025), explodes conventional notions of gender while unapologetically holding its ground against detractors. Its exaggerated proportions invite a smile, while the constricting coils at its feet introduce a meaningful impediment to movement. Technically, Spinal Tap (2025) features the most distinctive and challenging glaze. Appearing somewhere between lifeless sea coral and overheated Styrofoam, the piece commands attention with a crescendo of natural forces, even as its two playful synthetic ponytails inject a note of wry humor. This interplay of texture, anatomical specificity, and mischievous wit epitomizes the tone and tenor of Jaffe’s work overall.

Jaffe’s brilliance translates seamlessly into her two-dimensional works as well, including woven cotton wall hangings and multimedia drawings. When viewed alongside her sculptural objects, they evoke comparisons to Louise Bourgeois, particularly in their biomorphic forms and references to sewing and seamstressing. Flow (2021) is especially compelling for its stitchwork, dangling hands, layered metaphors, and subtle allusions to molecular science, lending it the quality of early, apex Surrealism.

Occupying a separate area on the main floor of L’Space are the mixed-media works of Emilio Martinez. Like Jaffe, Martinez creates an alternate-world sensibility, though his work is inflected with explicit references to Christianity. In Modern Jesus (2025), these beliefs are made overt through the inclusion of a crucifix and the inscribed phrases “stay home… have faith… there’s power in the name of Jesus.” In most of the roughly twenty other works, however, the religious references remain understated unless one consults the titles. What consistently emerges instead is a haunting darkness softened by hopeful, searching eyes—eyes that elicit empathy and forge an immediate emotional connection.

Emilio Martinez, Family in the Garden, 2025. Acrylic paint, charcoal, and graphite on art history book page, 17 × 12.5 in. Courtesy of L’Space Gallery.

Martinez, who immigrated to the United States from Honduras at the age of thirteen, is a self-taught painter who confronts his inner struggles with unwavering faith. Frequently working on pages torn from history books, he creates compelling contrasts between the saccharine and the soulful. Black and red dominate much of the work, while The Wedding (2025) and Family in the Garden (2025) stand out for their use of colorful book pages. This shift allows the palette to expand and softens the transition between source material and intervention. In Family in the Garden especially, a shimmering effect emerges as Martinez’s color sensibility bridges the gap between the pre-existing narrative and his own hand. The scene depicts a small gathering—perhaps four or more figures—who appear to hear our approach and suddenly turn toward us, their moment of amusement interrupted by our presence. This implied action is central to Martinez’s practice: the viewer is immediately drawn into the drama, summoned by eyes that see us clearly and invite a shared, synchronous engagement.

There is also a vein of autobiographical humor running through Martinez’s work. The New Kid on the Block (2024) exemplifies this quality. Here, Martinez paints over a pre-existing illustration depicting a passerby on a sidewalk beside a white picket fence. In the original image, a figure on the second floor of a dated North American home waves as if to say, “I’ll be right there.” In Martinez’s reworking, a long-eared figure twists its head completely around to address us, while a second figure—added by the artist—observes from a first-floor window. The awkwardness of the main figure, along with the deliberate misalignment of white-laced red shoes and their shadow, reveals the freedom with which Martinez approaches both thought and paint.

One may also note the source of the original illustration in The New Kid on the Block, which reads: “The Magic Football” by R. H. Barbour, St. Nicholas, December 1914, Collection of Norman Rockwell. This reference is significant, as Rockwell—renowned for his idealized visions of Americana—represents, for Martinez, the shock of encountering a new homeland and its accompanying belief system, often framed as “the American Way.” This tension becomes even more apparent in The Baptism (2024), where Martinez intervenes on a reproduction of a Saturday Evening Post cover, a publication central to Rockwell’s legacy. By asserting his own contemporary reality, Martinez offers U.S.-born viewers insight into the challenges of navigating radically different cultures at a formative age. Ultimately, he relies on faith to guide him through these complexities, granting him his own sense of “Freedom From Fear.”

“Jeanne Jaffe: Becoming Hybrid” and “Emilio Martinez: Freedom From Fear” are on view at L’Space Gallery on 19th Street in Chelsea through January 31. Do not miss it.