Susan Inglett Gallery

By D. Dominick Lombardi

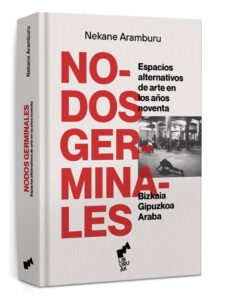

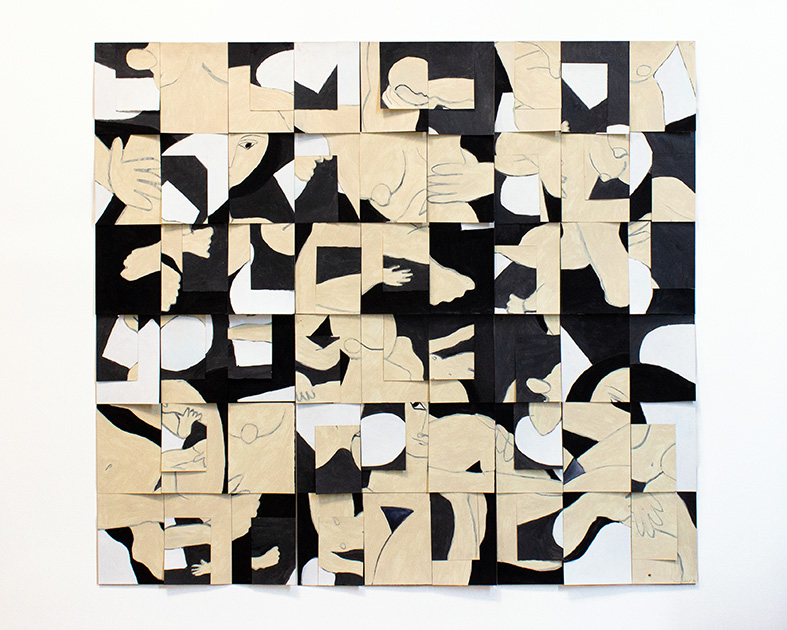

SUSAN WEIL. Color 11, 1999

Acrylic, charcoal and watercolor on paper. 60 1/2 x 66 1/4 in

Copyright The Artist. Courtesy of JDJ Gallery and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.

THE BOYS CLUB, curated by Cortney Connolly for the Susan Inglett Gallery, is a timely and essential exhibition of seven LGBTQIA+ creative’s contributors to the principles of Pop Art. As referenced in the curator’s essay, THE BOYS CLUB is a response to the missing “demographics not originally included in the Independent Group (queer and femme).” The Independent Group of artists was originally championed by the art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway some 70 years ago. Held at the historic Whitechapel Gallery of London, those early Pop Art exhibitions in the mid-1950s were meant to establish the tenets of the genre by featuring British post-war Pop protagonists such as Richard Hamilton and Nigel Henderson. THE BOYS CLUB is Connolly’s response to such general oversights, adding much-needed diversity to the tenets of Pop Art.

MARILYN MINTER. Nuzzle, 2022

Dye Sublimation Print. Edition 1 of 3 + 2 AP. 40 x 30 in.

Copyright The Artist. Courtesy of Salon 94, NYC and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.

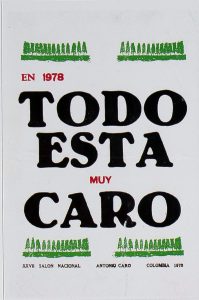

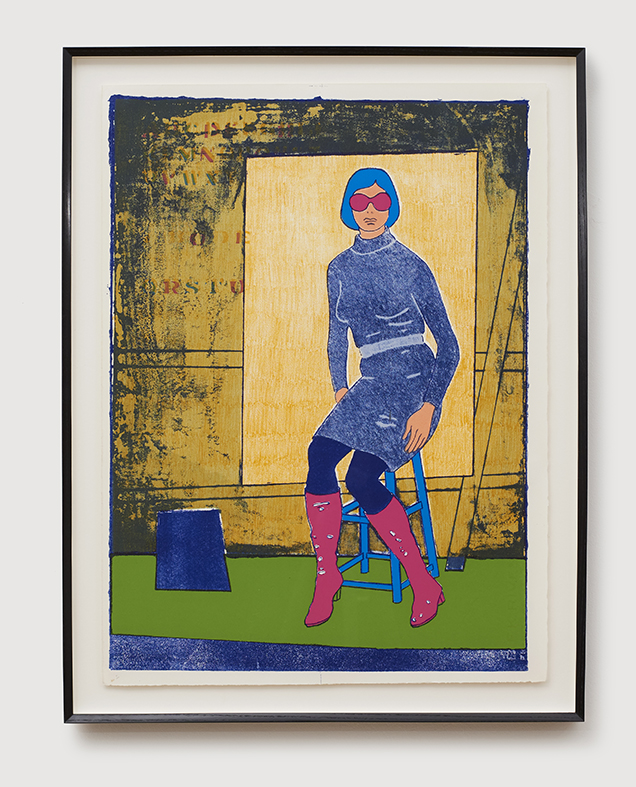

Most of the art in the exhibition are works created in the past 20 years. However, the two exceptions to the timeline are Susan Weil’s Untitled (1998), an assembled, disjointed, and disorienting grid-type collage that reveals jumbles and cropped sections of figures that challenge the viewer’s sense of connectivity. The second is Erica Rutherford’s very classic-looking Pop Art lithograph of a colorfully costumed heroine rattled out of repose in the print titled The Startled Model (1977). Here, you can clearly see Pop Art elements such as areas of unmodulated color, stenciled text, and Mod era fashion.

With Pop Art in general, there is often the presence of popular culture, especially the element of the direct capture of visual imagery from known printed materials. For example, Beverly Semmes begins two paintings, Green Shoe (2024) and Eye on Blue (2024), with enlarged photographs from vintage men’s “nudie” magazines. The enlargements are so extreme that the original dot matrix color printing process used to mass-produce the magazine creates a rather sterile, albeit curious, quality to the background surface. Over this, Semmes over-paints large areas with acrylic paint to block out the racy anatomical details. In doing so, the artist refocuses the eye of the viewer beyond the objectification of women to more captivating color-wise compositions that are more positive and pleasing to the eye.

ERICA RUTHERFORD. The Startled Model, 1977

Lithograph on paper. Unnumbered AP from the edition of 6, plus Aps. 22 3/4 x 17 in.

Copyright The Artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, NYC and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.

Nina Hartmann also utilizes photography, albeit elongated and distorted, to reorient one’s perspective relative to narrative space in a very Modernist way. Hartmann’s Mind Control Image Connectivity (Maze B) (2024) is also a participatory work, whereby the horizontal stainless steel slats that traverse the picture plane can be moved carefully with gallery assistance. The red, black, gray, and white palette and the distinctive shape of this distinctive work subliminally suggest a spinning motion that slowly works its way into the viewer’s subconscious, as suggested in the title. Troy Monte’s Michie’s Phases (2020) has a number of diverse materials collaged across the surface in distinct sections, presenting a very complex narrative. The key here is more or less men’s fashion extremes over the decades, including Zoot Suits, a classic black-trimmed, white prom tuxedo jacket, and traditionally dressed Mexican mannequins. Most of the human faces are carefully cut out, adding a bit of ferocity to the individual vignettes. At the same time, the many materials used harkens back to the mid-twentieth century mixed media craze most common in Pop Art. The overall effect of Phases has its own brand of timelessness, while the banded or flag-like composition commands one’s attention.

Natalie Ochoa has three works in the exhibition, all with tinges of humor and playfulness that will pique viewer’s curiosity. The one that greets you when you first enter the gallery is Untitled 1 (2023), a digitally embroidered scene of a vaguely familiar flying penguin delivering a pack of Kool cigarettes – much like a stork would deliver a baby in cartoons. The text at the bottom right says: “for a lifetime of MORE PLEASURE,” while the white and blue ribbons surrounding the design in a radiating circle give off the thought “it’s a boy.” Much of Ochoa’s work has that tongue in cheek approach when toying with familiar clichés, often extending the narrative into deeper or darker territory, while the talent and inventiveness here is unmistakable. Marilyn Minter’s Nuzzle (2022) is the most voyeuristic work in the exhibition, which is very much part of the artist’s history. Peering through a foggy, drippy shower door, we see a more mature couple at a tender moment in mid-caress. A narrative made a bit more sexy with the shiny fabrics worn and the heat lamp tint to the flesh. By partially obscuring our view, Minter brings us right into the narrative as our curiosity stirs and our own body image inhibitions come to mind.

If you find yourself in Chelsea before January 25, 2025 you should stop in and see THE BOYS CLUB. It is a refreshing take on the Pop Art movement, adding many new voices to the conversation. The gallery will be closed for the holiday beginning December 21st, reopening on January 2nd, 2025.

Natalie Ochoa. It Came On A Wagon, 2024

Found objects, ripstop, latex vinyl, digital embroidery and laundry basket

33 x 25 dia. in. (NO0001)

Copyright The Artist. Courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.