Feminist Intersections of Memory, Body, and Power in the Work of Quintero Castañeda, M. Roa, Pachón, and Valencia.

By Ma. del Pilar Vergel, PhD.

The contemporary artistic practices of four creators from Cali, Colombia, combine art and, in some cases, artivism from an intersectional perspective. These proposals challenge dominant narratives about the oppression and exclusion of marginalized identities. Based on Rancière’s ideas about the “distribution of the sensible,” these artists’ expressions contribute to transforming the relationships of perception and social participation, giving voice to silenced subjects and strengthening subaltern subjectivities. Through the recovery of ancestral memories, symbolic appropriation of spaces, and the creation of visual and performative discourses, these practices promote the decolonization of imaginaries and social spaces, confronting structural inequalities and fostering inclusion. In this process, art ceases to be merely a reflection of reality. It becomes an active tool of collective agency, fostering more participatory, critical, and resilient communities that influence social and cultural transformation in the face of persistent colonial logic.

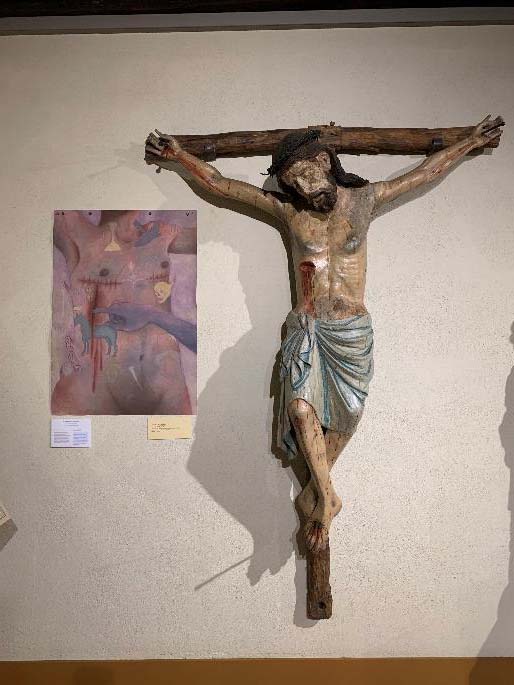

Saro Agustina Pachón. Right on the wound (Justo en la Herida). Oil on Canvas. Photography. Crucifix. Museum of Sacred Art of Bilbao.

First, three terms, coloniality and decoloniality, are reviewed from an intersectional perspective, as proposed by Lugones (2008)1. Her approach includes decolonial feminism, queer theory, and embraces transfeminism. Through the analysis of the artistic practices of these four creators, the ideas presented by Rancière (20092) regarding the distribution of the Sensible are revisited, specifically how existing power structures determine the distribution of the visible and the audible in a society. Rancière argues that art can alter these power relations and that the artist’s role is to generate new ways of seeing and understanding the world.

Coloniality, as defined by Quijano (2014)3, refers to the persistence of colonial structures in contemporary societies that reproduce patterns of discrimination and exclusion affecting subaltern populations. Reviewing the colonial discourse is crucial to incorporating marginalized voices, thus enabling a more comprehensive understanding of historical and cultural processes in Latin America (Díaz, 2014)4. From this perspective, Rancière (2009) argues that politics extends beyond mere power management, involving a reorganization of social relations that enables the opening up of silenced voices and transforms the distribution of experiences and knowledge in society.

Quijano (2014) introduces the concept of coloniality of power to explain how these structures continue to influence the present, manifesting in forms of ethnic domination. Complementing this view, Lugones (2011, 2014)⁴5 extends it through the intersectional analysis of race, gender, class, and sexual orientation, highlighting the experiences of those who face multiple forms of oppression. Within this framework, the decolonial approach proposes dismantling power structures to restore the dignity of colonized peoples.

Consequently, decolonial feminism challenges the structures that have oppressed women and queer people in racialized contexts, making visible the experiences of historically excluded groups. In this regard, art emerges as a powerful medium to question the distribution of the sensible, generating new forms of perception and experience of the world. Through dissensus and the construction of new subjectivities, art becomes a vehicle of social transformation, challenging established norms. This capacity for resistance and resignification manifests in the artistic practices presented below.

Rewriting History: The Trace of Afro-Women in Collective Memory

The artist Vanessa Quintero Castañeda developed a photographic project titled In Search of the Black Trace: African Presence in Guanajuato, in which she investigates the existence of enslaved African women, ladinas, and wet nurses in Mexico, highlighting their significant role in Latin American history. Her research reveals a lack of recognition of the Black population in Mexican history and collective memory despite their relevance as key labor since the 17th and 18th centuries. This invisibilization is attributed to the colonial regime, the caste system, and social pressure to assimilate, which led many Afro-descendant individuals to deny their roots.

During slavery, a strategy was implemented to make African people forget their origins and adopt an identity imposed by Europeans. However, enslaved women found ways to preserve their identity despite internal discrimination, generating tensions within these communities. Thus, Black and mulata women in New Spain used their sensuality as a strategy for integration, which generated ambivalent perceptions: they were seen as joyful and virtuous but also as lustful and associated with witchcraft (Quintero, 2019)6.

Vanesa Quintero. Cimarrona, In Search of the Black Print series, (serie: En busca de la huella negra). Photography.

Quintero assumes the identity of these women, setting aside her subjectivity to empathize with those who are part of both her personal and collective past (Quintero, 2020)7. This act of mutual recognition intertwines the conditions and roles of each. Her portraits, situated within the context of political action, question, challenge, and subvert the “distribution of the sensible,” presenting alternative ways of seeing and experiencing the world of Afro-descendant women, both during the colonial period and in the present day.

As an artist, she seeks to generate dissensus and put colonial dynamics that persist in our cultures into tension, illustrating cycles of oppression and resistance. In this way, she makes historical and contemporary injustices visible, promoting the dignity of Afro-descendant voices and contributing to the rewriting of history from previously relegated perspectives that are fundamental to the social fabric.

Challenging Narratives: Pocahontas and La Malinche in the Fabric of Identity

The transcultural artist Yohanna M. Roa’s performance, “Pocahontas and Malinche: An Encounter at Governors Island” (2023)8, problematizes the mythification of these two indigenous figures, perceived as the mothers of mestizaje in America and subject to multiple interpretations. Despite similar life trajectories—coming from noble families, being partners of Europeans, and dying young—their stories have been constructed from a Eurocentric perspective that conditions their legacy. Pocahontas is represented as “the good Indian,” protective and loving, while La Malinche has been condemned as a traitor for her role as interpreter and lover of Hernán Cortés.

Yohanna M. Roa. Pocahontas and Malinche, An Encounter At Governors Island, NY. Performance. 2023

In this context, the performance questions the imposed categories assigned to both figures, as well as the authorship of their stories and the purposes behind their incorporation into the nationalist narratives of their respective countries (Roa, 2023).

From a decolonial perspective, this performance highlights the complexity of representing these women, challenging historical narratives forged by colonialism, patriarchy, and nationalism. It makes evident the need to decolonize history narrated from dominant perspectives that have silenced indigenous peoples. Roa’s critical analysis, from a decolonial feminist standpoint, seeks to demystify the Eurocentric and patriarchal narratives surrounding these figures. By interrogating these dominant stories, the performance calls for recognition of Indigenous histories through their voices, emphasizing their agency and resistance against colonization and oppression.

Yohanna M. Roa. Pocahontas and Malinche, An Encounter At Governors Island, NY. Performance. 2023

The performance’s staging at Governors Island symbolizes a confrontation with colonial history and the presence of colonizers in that space. This gesture not only questions the colonial narrative established there but also claims space for Indigenous expression and resistance, strengthening the struggle for the decolonization of both physical and symbolic spaces, as well as for the vindication of Indigenous voices in the construction of collective memory.

Bodies of Resistance: Transgressions and Identities in Sacred Art

Saro Agustina Pachón identifies as a transfeminist, a movement that seeks liberation through the deconstruction of binary gender and heteronormative norms. This approach combats patriarchy, transphobia, sexism, and discrimination, promoting safe and inclusive spaces. It also advocates for the representation and visibility of trans and non-binary experiences, grounded in an ethic of solidarity among dissident identities.

In her pictorial work, developed within a religious context, Pachón employs painting as a tool to intervene in collective consciousness and generate political and social impacts that strengthen memory and community identity (Amao, 2022)9. Her work is situated in contemporary artivism, where queer theory is central to challenging norms of gender and sexuality, promoting diversity and equity.

Pachón (2024)10 questions toxic masculinity and reflects on gender dysphoria, addressing discomfort with imposed identity expectations and reclaiming the freedom not to conform to normative demands. Enjoyment of activities traditionally assigned to different genders becomes a form of resistance and personal affirmation.

Her piece Justo en la Herida (Right on the Wound) is provocative and symbolic: it depicts a body with wounds on the chest, evoking the bodily interventions some trans people undergo to align their bodies with their identities. The image references the body of Christ crucified, challenging traditional religious codes by fusing Christian iconography with gender struggles. The work tensions the relationships between identity, spirituality, and coloniality, making visible the symbolic and material violence inflicted upon subalternized bodies.

Saro Agustina Pachón. Right on the wound (Justo en la Herida). Oil on Canvas. Museum of Sacred Art of Bilbao.

The grid over the body, evoking colonial maps used to loot territories, guides a narrative that alludes to both plunder and concealment beneath a religious gloss. In this way, Pachón questions power devices that have legitimized control over bodies and cultural appropriation, proposing that art serves as an act of resistance, memory, and transformation. This piece, produced during her master’s studies, confronted Spanish professors who reduced her work and experience to a mere anecdote, considering it “typical of Latin America.”

The Visceral, the Monstrous, and Dissensus: Hearts that Transform into Heads

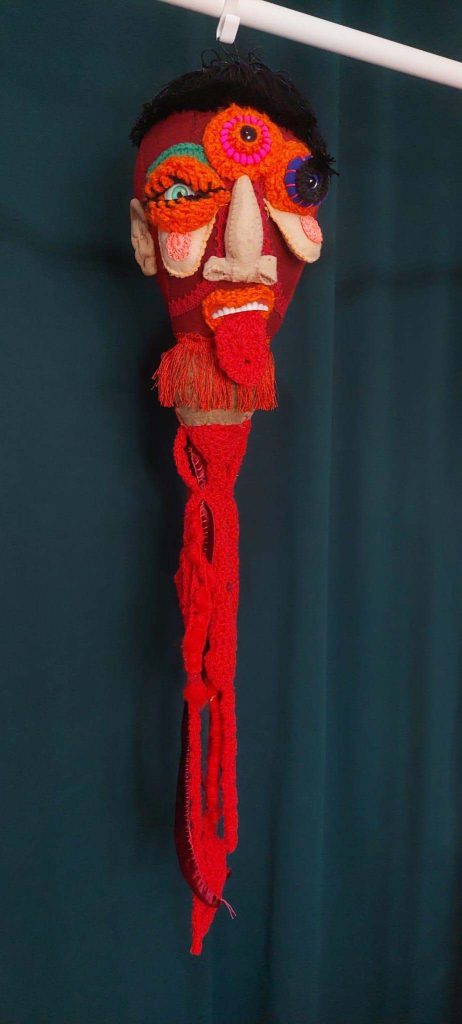

Andrea Valencia’s work⁸11 situates itself at the intersection of art, activism, and dissidence, challenging colonial structures that shape what is visible and sayable. Her sewn hearts, created during the pandemic as an intimate gesture of mourning and connection with her ancestors, become strange organs—with vaginas and eyes—symbolic devices of transgressive meaning that re-signify the Sacred Heart of Jesus. This operation responds to the “distribution of the sensible,” redistributing what deserves to be perceived, felt, and thought.

From a decolonial and intersectional feminist framework, Valencia denounces the violence inscribed on racialized and feminized bodies. Her heart-vaginas allude not only to repressed desire and denied sexuality but also stand as symbols of creative power. Embroidery, for her, is a strategy of healing and political action: a way to rewrite history from the gut.

Inspired by the legend of a dismembered Inca, she transforms these hearts into a severed head of a “cholo,” titled I Will Return and I Will Be Millions, an Andean annunciation claiming the return of what was violently suppressed. This sculptural mutation embodies the “coloniality of power,” revealing how the conquest fragmented not only bodies but also worldviews. Against this, her visceral aesthetic becomes an act of resistance that revalues the monstrous and the wild feminine.

Andrea Valencia. From left to right: (Nataliecoraxon) “Heart”, Soft Textile Sculpture Series, performance. Berlin, 2024; I Will Return and I Will Be Millions. Textile sculpture. Performance action. Lisbon; “The Witcher”. Soft Textile Sculpture Series. 2025.

Valencia’s work confronts the legitimizing logic that reduces Latin American art to mere experience or an “anecdotary” (Mignolo, 2010)⁹12. Against the hegemonic gaze, she proposes an embodied art that claims other forms of knowledge not validated by Western science.

Her work subverts categories imposed by colonialism, opening a space for dissensus in which the intimate is political and the monstrous serves as a tool to unsettle and resist. Thus, she not only creates objects but also reorganizes ways of feeling and thinking about the social through a deeply situated artistic practice.

- Lugones, M. (2008). Colonialidad y género. Tabula Rasa, 9, 73-101. https://www.revistatabularasa.org/numero-9/05lugones.pdf ↩︎

- Rancière, J. (2009). El reparto de lo sensible: Estética y política (Primera ed.). LOM Ediciones.

https://eva.isef.udelar.edu.uy/pluginfile.php/66459/mod_resource/content/1/Ranciere%2C%20J.

%20El%20reparto%20de%20lo%20sensible-%20estética%20y%20polÃ%C2%ADtica.pdf ↩︎ - Quijano, A. (2014). Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. En Cuestiones y

horizontes: De la dependencia histórico-estructural a la colonialidad/descolonialidad del

poder (pp. 431-455). CLACSO. https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20140507042402/eje3-8.pdf ↩︎ - Díaz, M. (2014). El “nuevo paradigma” de los estudios coloniales latinoamericanos: un cuarto de

siglo después. Revista de Estudios Hispánicos, 48, 101-122. ↩︎ - Lugones, M. (2011). Hacia un feminismo descolonial. La Manzana de la Discordia, 6(2), 105-

https://doi.org/10.25100/lamanzanadeladiscordia.v6i2.1504 (2014). Colonialidad y género: Hacia un feminismo descolonial. En W. Mignolo

(Comp.), Género y descolonialidad (2a ed., pp. 13-44). Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Del Signo.

https://www.lrmcidii.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Genero_y_Descolonialidad.pdf ↩︎ - Quintero Castañeda, C. V. (2019). En busca de la huella negra: Presencia africana en Guanajuato (Tesis de maestría). Universidad Iberoamericana León.

https://repositorio.iberoleon.mx/server/api/core/bitstreams/c2af9a91-3661-4ea0-940b-1545b46a223e/content ↩︎ - Quintero Valencia, C. F. (2020, febrero 13). En busca de la huella negra: presencia

africana en Guanajuato [Exposición de arte]. Galería Humberto Hernández – Centro

Cultural Colombo Americano, Cali, Colombia.

https://vanessaquinterocastaneda.com/exposiciones/ ↩︎ - Roa, Y. (2023, julio 24). Pocahontas and Malinche, at the Thyssen Bornemisza Museum.

Yohanna M. Roa. https://yohannamroa.net/2023/07/24/pocahontas-and-malinche-an-encounter-at-governors-island/ ↩︎ - Amao, M. (2022). Artivismo: Disputa estético-política por la memoria colectiva. Estudios del

Discurso, 8(1), 108-123. ↩︎ - Pachón Peláez, S. (2024). Sanguaza [Documento inédito del máster en Pintura,

Universidad del País Vasco]. ↩︎ - Valencia, A. (2025, 10 de junio). Andrea Valencia Art. https://www.andrea-valencia.com/#page-top ↩︎

- Mignolo, W. (2010). Desobediencia epistémica: Retórica de la modernidad, lógica de la

colonialidad y gramática de la descolonialidad. Ediciones del Signo. ↩︎