By Luis Felipe Vélez

Cultural Center and Departmental Institute of Fine Arts

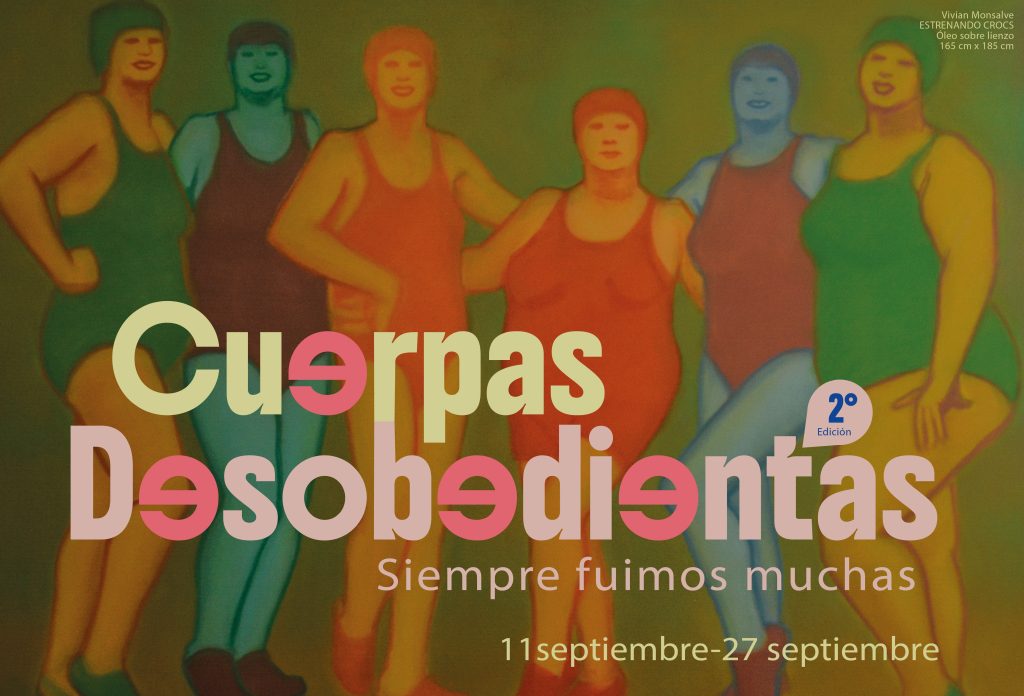

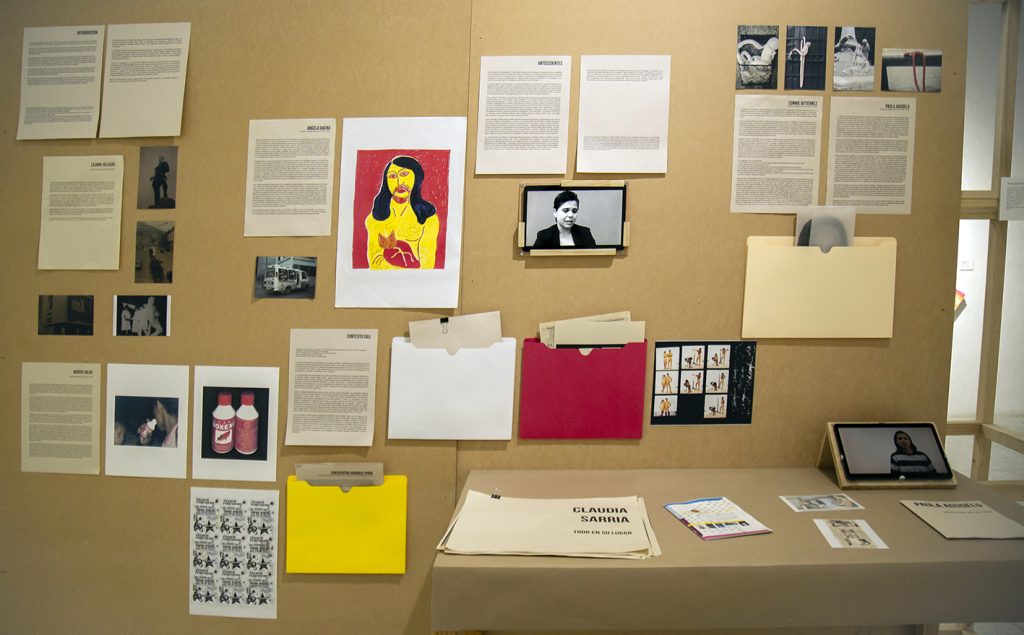

Curated by Yohanna Roa, September – October 2025

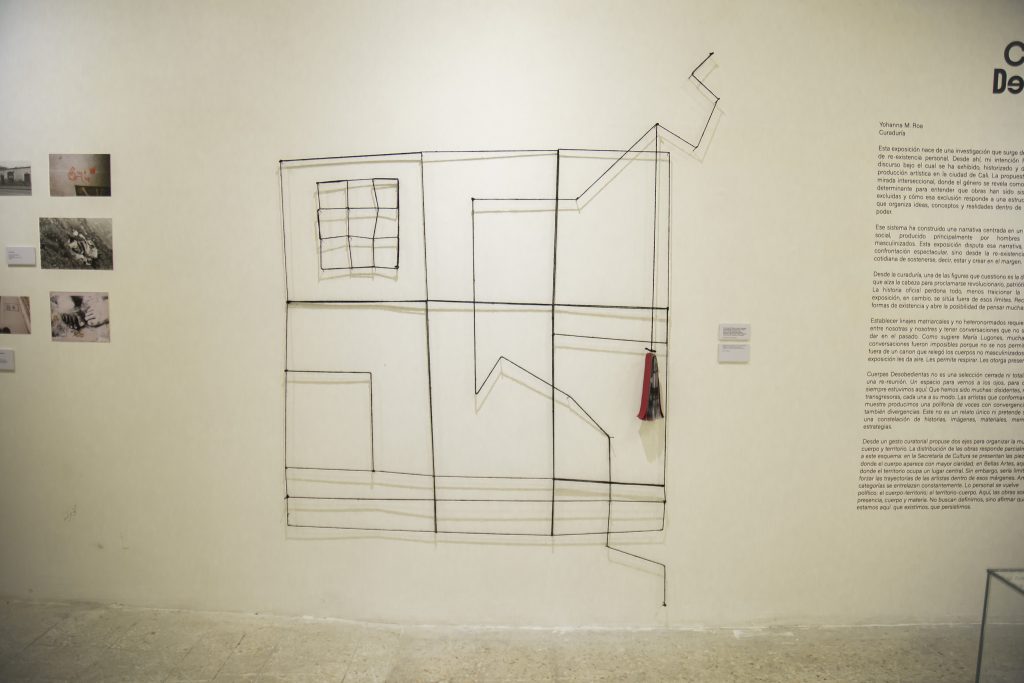

Instituto departamental de Bellas Artes. Exhibition view. Photo INES_Magazina

Curatorially Unruly Bodies proposes a reading of what we call the body as a symbolic battlefield of multiple dimensions. Through two exhibitions, seminars, workshops, and the publication of a book bearing the same title, the project confronted theoretically and practically the fragility and contradictions of systemic structures and the particular habits shaped by normative cultural repetitions.

Divided into two venues, one at the Secretariat of Culture and the other at the Institute of Fine Arts, the exhibition gathered over forty artists who, through their practices, wove an affective and situated map, representing the context while inhabiting and voicing it through the power of a living discourse.

In the first venue, the Cultural Center of Cali, the body emerged as a sensitive axis. These undisciplined, rebellious, and fragmented bodies questioned the norms imposed by gender, race, and social class. In the second, presented at the Institute of Fine Arts, territory was conceived as an expanded body: a space where memory and geography are interwoven to resist colonial forms of representation and appropriation. Both instances operated as mirrors of a single question: in what ways can human, territorial, and symbolic bodies once again become sites of enunciation rather than instruments of domination?

Cali Cultural Center. Exhibition View. Photo Antonio Juarez Caudillo

Yohanna M. Roa’s curatorial approach traced the origins of these reflections across the last four decades, articulating the works to create atmospheres and tensions within a conceptual field that overflowed the relations between them, binding them as a whole. Like the air collectively breathed in the galleries, without distinction, in the very act of life: inhaling, exhaling, being with the environment, the earth, and the space where the exhibitions unfolded.

In that place where the human dissolved and the sensorial became collective, the shared breath reopened a path toward meaning, toward understanding what it means to disobey as a body, and more so, how one inhabits a territory when the land itself has been wounded. In this gesture, recalling a “resistance from the intimate,” the exhibitions reconfigured the gaze, compelling viewers to abandon the comfort of distant viewer.

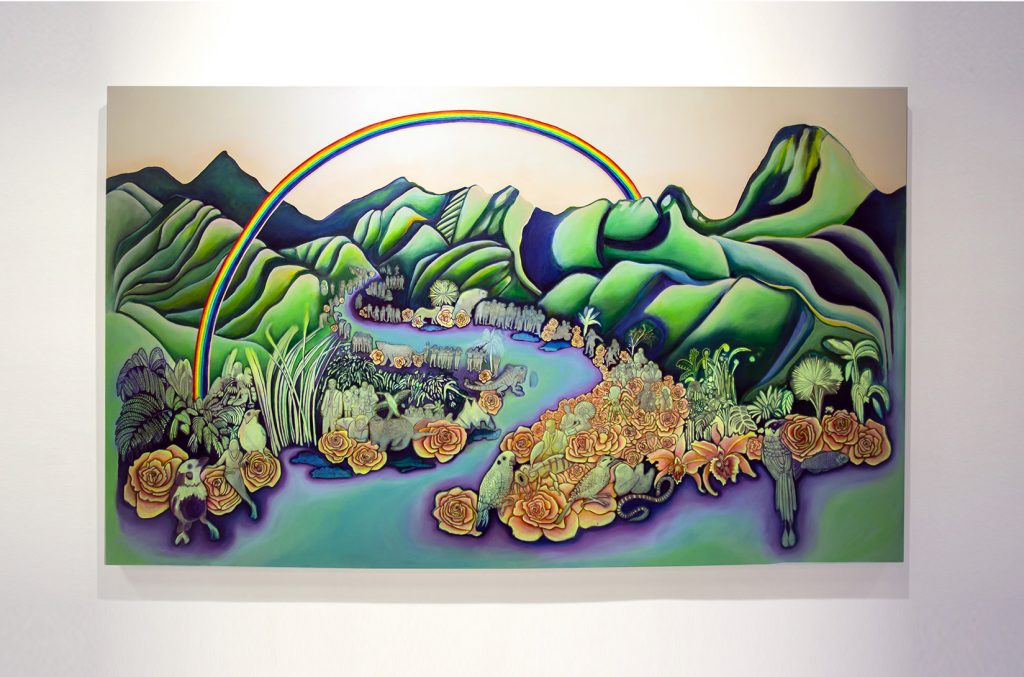

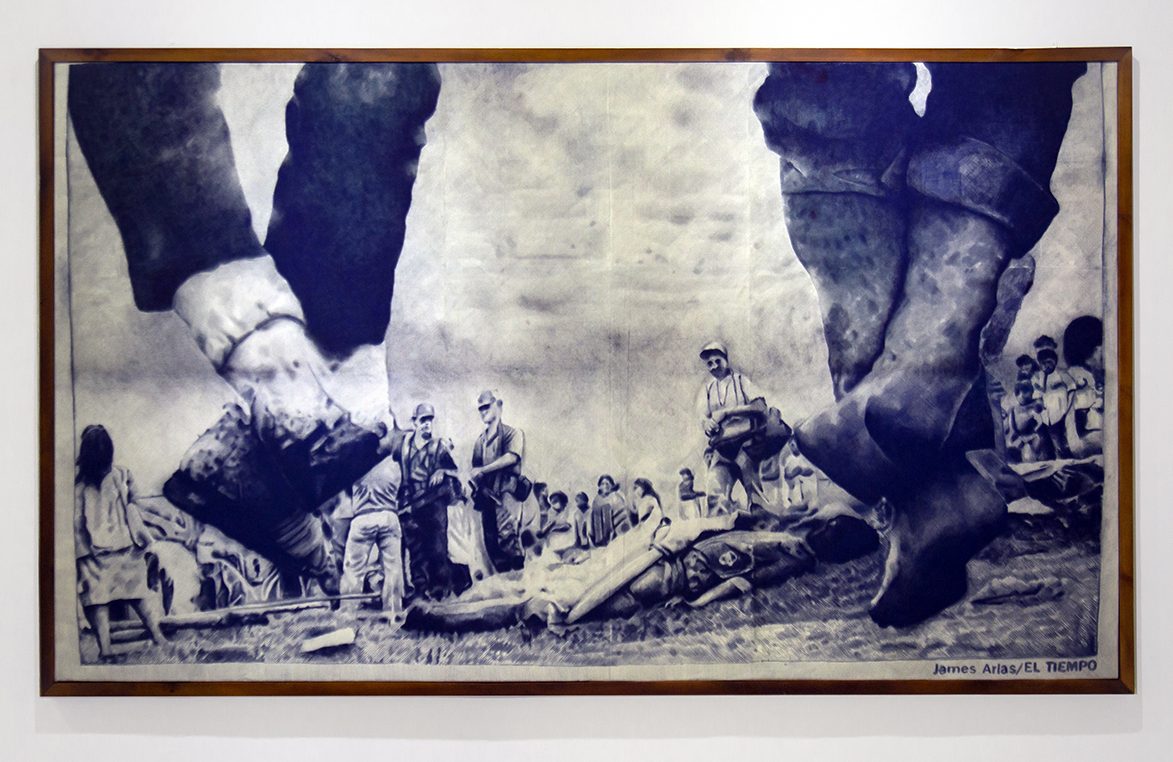

Left: Río Nuevo (New River). Ana María Velasco. 2,50 mts x 1,50 mts. Acrylic on Canvas. 2025 Right: Process for Memory (Blue Drawing), photograph published in El Tiempo newspaper, 1991, Angélica Mercedes Castro, 300 cm x 250 cm, tracing with blue carbon-sensitive sheet on coastal canvas. 2021–2023. Photograph courtesy of Instituto Departamental de Bellas Artes – María del Mar Castro.

Inhale

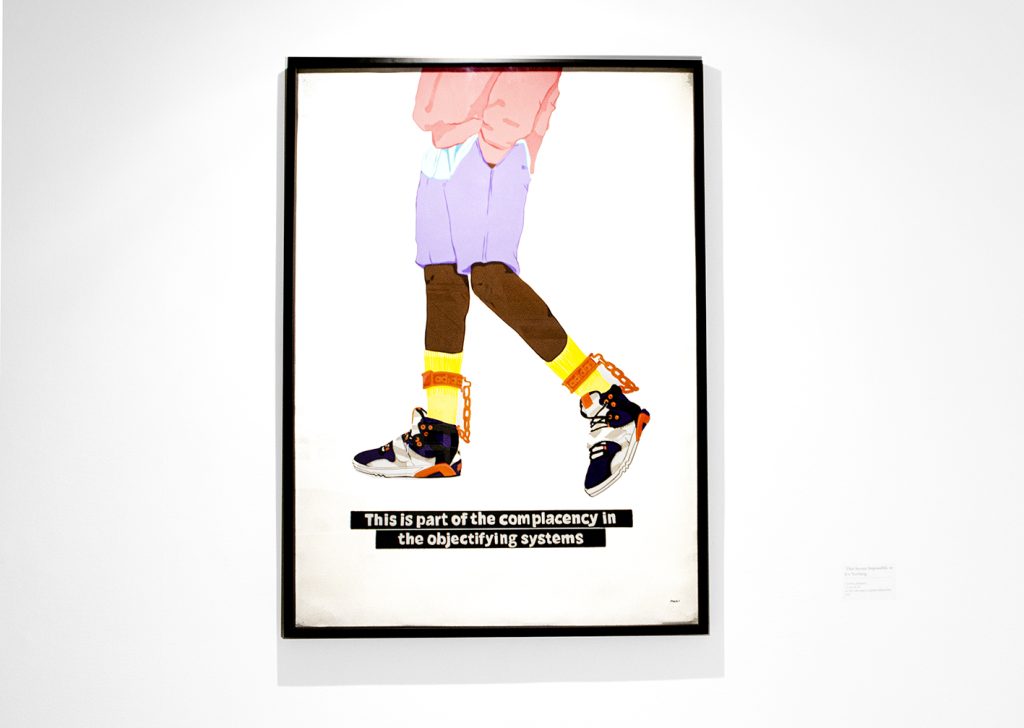

In the first venue, bodies appeared as living archives, surfaces upon which the violence of history and the impulses of re-existence were inscribed. One might read this as an exercise in visual decanonization through performativity, self-perception, and the use of the body as language. The artists subverted binary categories to construct a new symbolic field. Within this weave, intersectionality operated as a prism revealing how forms of resistance interlace, unfolding practices that interrogate the gaze and its colonial genealogy.

Justo en la Herida (Right on the Wound). Saro Pachón Peláez, 60 cm x 50 cm, Oil on canvas, 2024.

Saro Pachón’s painting Justo en la herida (Right on the Wound, 2024) confronts us with the power of honesty: a self-represented body that transcends image to delve into the first vital space that contains it. From there, it traverses the archive of history, where “The relationship between body and subject is traversed by power and by the ways in which it binds certain bodies to the ‘types’ of subjects privileged by society,”[1] to arrive at rupture through disobedience not in what is shown, but in how it is shown: in the refusal to offer docile images, in the insistence on occupying space with unfinished, uncomfortable forms that dismantle the fictions separating one human from another.

JohnaJohn Campo Betancourt. Art of the Tramoyo 3.0. 2.50 m x 5 m. Installation. 2025.

This relational process took tangible form in JohnaJohn Campo’s Weaving a Tender Refuge with Foam (2025). Using fragments of foam joined collaboratively by the audience, Campo revisits the body’s experience in drag culture, where this material serves multiple purposes, generating interconnections of stories that form a common whole within the plural existence of identities. This act of invention recalls the body as both an escape route and a contested territory.

Sweet Drops. Janeth Blanco Parra, Variable dimensions, Performance, 2025. Photos by Antonio Juárez Caudillo.

The activation of Janeth Blanco’s performance Sweet Drops (1997–2025)[2] intensifies this relation by appearing crowned with roses that stand upright on her head, gently bathing her with the weight of symbols of beauty and sacrifice. In her slow walk, enduring the thorns dressed in a gown made of petals from the same flower, she maintains a solemn gesture, a living metaphor that every political transformation begins in the skin and in the gesture. In Yumbo[3] (2019), Dayana Camacho evokes the memory of the familiar through the construction of intimate narratives that, in turn, generate a sense of collective belonging, stories told and recorded that bind a shared past through affect.

Roa’s curatorship wove this collective learning without aestheticizing suffering, transforming the galleries into spaces of symbolic repair and restoration of dignity. Within this field, bodies ceased to be objects and became political and epistemic subjects. Bodies as forms of knowledge and ways of producing meaning from situated experience: thus, the exhibition can be read as a laboratory of reconstruction, where artists reconfigure their being-in-the-world through memory, desire, and scar establishing a mosaic of stories that evade totalizing representation, insisting instead on multiplicity, the right to exist on one’s own terms, and the urgent need to imagine possible worlds.

Yumbo. Dayana Camacho Rodríguez, 180 cm x 120 cm, Oil on canvas, 2019.

Exhale

The bodily disobedience that emerged in the composition of these spaces was ontological it required a shift: from conceiving subjectivity as a network of relations situated in history to understanding it as embedded in territory and community.

The second venue unfolded expansively: if the body is territory, then it feels, it remembers. The ground became both witness and accomplice. This body-earth, mourning colonization, war, and extractivism, turned into fertile soil for art as a living act. During this transition, new modes of being emerged.

Left Analog Hydrophone, Series Technologies for Listening to Water. Laura Victoria Cuellar, 200 cm x 15 cm, assembled copper. Mixed media, 2023. Right A House from El Rodeo, on the Road to Paradise, Crossed by the Map of the Places My Mother Inhabited in Life. Belonging to the project Gestures, Archives, and Affective Repertoires in the Face of the Absence of Bodies and Memories. Cindy Muñoz Sánchez, 150 cm x 150 cm (complete wall installation), 2014–2025. Photograph courtesy of Instituto Departamental de Bellas Artes – María del Mar Castro.

In Laura Victoria Cuéllar’s Analog Hydrophone. Series: Technologies for Listening to Water (2023), the search for the poetics of origin lies between sensitivity and instrumentality, a means of capturing the earth’s breath within the water, within the river that flows as time’s constant, listening to the territory from its most ancestral resonance. In A House from El Rodeo, Path to Paradise Crossed by the Map of Places My Mother Inhabited in Life (2014–2025), Cindy Muñoz Sánchez constructs what might be called home through inquiry and movement. Each point in this imagined house traces a path marked not only by survival but by the creation of other modes of existence, affirming roots while inventing new ways of inhabiting.

POP Justice. Alejandra Gutiérrez. Variable dimensions. Performance. 2025. Photos by Antonio Juárez Caudillo.

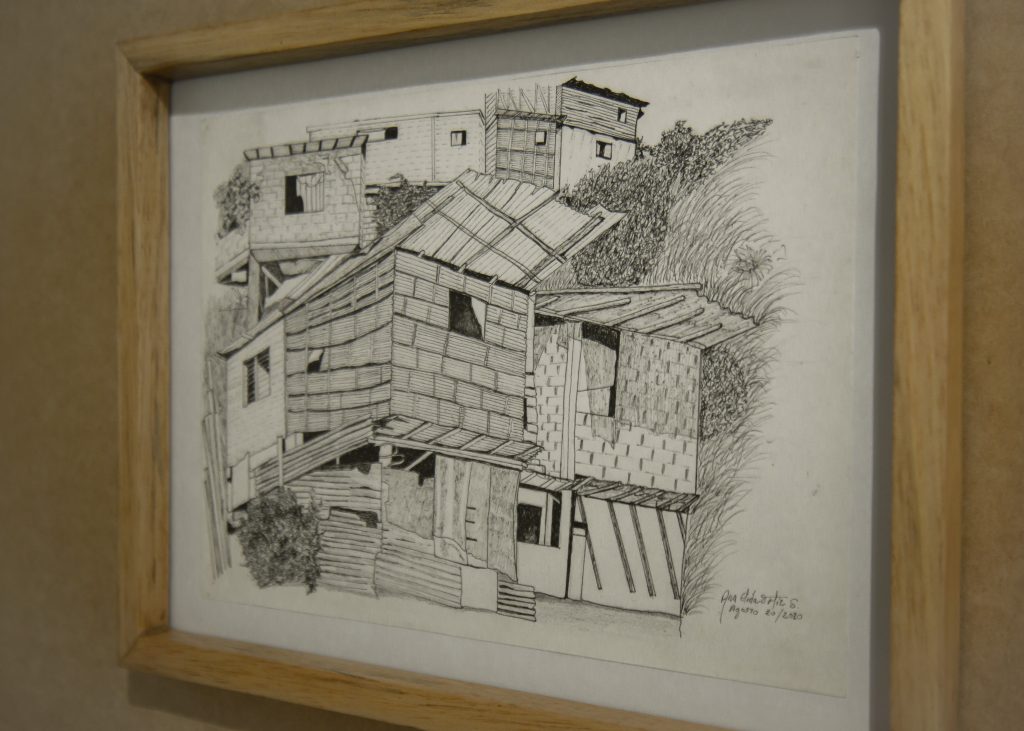

Ana Elida Ortíz, in Casa de Esterilla and La Guala (2018), builds from the everyday a relation where territory ceases to be a passive background and becomes a living subject that hosts and reconfigures the diverse presences that shape it. Paradoxically, it is from that same condition that inequalities are also normalized. In POP Justice (2010–2025), Alejandra Gutiérrez wheeled a popcorn cart on which she formed the word justice as people ate it, a never-ending act in which justice remains perpetually deferred, applying only to some while leaving communities waiting.

In the same room, Ángela Villegas’s Catenaries intervened the space with a hammock threaded with chonta thorns and the word forgiveness. Facing it, like a forming chorus, Angélica Castro’s Process for Memory (Blue Drawing) (2021–2023) establishes a dialogue between history and the weight of massacres in this nation. We see the backs of a pair of feet, resting on a wooden fence, contemplating a field of dead bodies. The scene reveals life as potential, something still breathing even through pain. This passage suggests a feeling that moves from bodily experience to territorial consciousness, revealing in every gesture an understanding of art as situated and relational practice, allowing the exhibition to function as a device for unlearning.

CATENARIES, (Perdon – Forgiveness) Ángela Villegas, installation 377 cm x 132 cm. Chonta thorns inserted into white hammocks,

Top Escorpión. Ana María Millán. 1,67 X 1,15 m. Pintura. 2025. Top Right: Mónica Restrepo.Still Life. 100 x 70 cm. The Seeds of Coming. 27 ceramic sculptures. Frit, Terra Sigillata, Burnished. Table. Variable dimensions. 2020 – 2024. Instituto Departamental de Bellas Artes courtesy – María del Mar Castro.

Both exhibitions, by bringing together diverse practices, generated a conversation that is also a crisis: How can we narrate multiplicity without erasing it? How can we look at pain without reducing it to an object of aesthetic consumption, and instead build community from difference? Unlearning the colonial gaze, the neutrality of art, and the idea of the body as private property here responds to an intersectional aesthetics in which difference is preserved through the persistence of each territory and gesture, with the intention of returning to the world with the desire to transform it. This reconfiguration of legitimization was manifested in the curatorial approach, which asserted that the goal was not to “represent a totality, but to open space for multiple stories.” Thus, the totalizing impulse of the modern discourse was deactivated, opening the way for practices that not only resist but also create other ways of living and narrating themselves.

Unrylu Bodies unfolded a visual critique of the patriarchal order, proposing a poetics of insubordination — an affective territory that claims its right to exist outside the mandate of the norm. In times marked by hate speech, censorship, and the precarization of life, these works reflect, gaze back, and challenge us. In that gesture lies the political strength of art that refuses to be silent: art that does not illustrate theory, but lives it. May this system, created with bodies in every aspect it addressed as a project—seminars, workshops, publications, exhibitions—serve as a path toward questioning and destabilizing established orders, reimagining other possibilities, and building from within the community. Beyond institutional politics, it speaks from what makes us human: from the very stimulus of our most common traits.

Only for life itself—for that which defends something as pure as what we are.

Participating artists in the exhibition: Ana María Rosero, Andrea Valencia Castrillón, Carmen Espinosa, Carmenza Banguera, Carmenza Estrada, Carolina del Llano Tafur, Claudia Inés Victoria, Connie Gutiérrez Arenas, Dayana Camacho Rodríguez, Ivonne Navas Domínguez, Janeth Blanco Parra, JohnaJohn Campo Betancourt, Liliana Vergara, Lina Hincapié, Luz Elena Villegas, María del Pilar Vergel, Natalia Cajiao, Vivian Monsalve, María Evelia Marmolejo, Ana Lucía Galvis, Leandra Plaza, Saro Pachón Peláez, Alejandra Gutiérrez, Ana Elida Ortiz Saldarriaga, Ana María Velasco, Ana María Millán, Ángela Villegas, Angélica Mercedes Castro, Cindy Muñoz Sánchez, Daniela Vargas, Diana Marcela Buitrón, Diana Saldarriaga, Laura Victoria Cuellar, Lina Rodríguez Vásquez, Lorena Tavares, Mónica Restrepo, Salomé Rodríguez, Raíz de Cero, Yasmin Romero Valencia, Yolima Reyes, Colectivo A la Plaza, Yohanna M. Roa.

In order, left to Right: “Still Life” Mónica Restrepo. 100 cm x 70 cm. Watercolor on Hahnemühle watercolor paper. 2024. “The Seeds Yet to Come”, 27 ceramic sculptures, 100 cm x 70 cm. Frit, Terra Sigillata, Burnished. 2020–2024. / “At Dusk”. From the series Inside. Luz Elena Villegas. Painting and printmaking. Colored metal. 2003. / “Self-Portrait” Lina Hincapié. 39 cm x 55 cm. Collage. Photography, painting, drawing. 2025. “Martyr I”. 48 cm x 60 cm. Mixed media. 2012. / “Bleeding Poppies 1, 2, and 4” Diana Saldarriaga. Variable dimensions. Wax and oil on canvas. 2012. / “Flora Floats in Desire II” Daniela Vargas. 59 cm x 94 cm x 20 cm each. Sculpture, installation. 2022. / “How Many Rivers Fit in a Black Crayon?” Raíz de Cero (Stephanie Díaz). 215 cm x 70 cm. Crayon drawing on blue paper (4 drawings total). 2023–2025. / Collective To the Square, Archive of Public Space Interventions in Cali, 1990–2005 / “Fanzine: An Archive of Artists, Arepera Workers, Travxs, Trans, Queers, Cuirs, and Others” Leandra Plaza. 250 cm x 100 cm (approx.). Artist’s book print proofs, printed in risograph and silkscreen. 2024. / “Woven-Palm House” and “The Guala” Ana Elida Ortiz Saldarriaga. 24.5 cm x 35 cm each. Technical pen on Durex paper. 2018. / Ivonne Navas Domínguez. Variable dimensions. 4-hour durational performance. Photographs by Antonio Juárez Caudillo. 2025. / This seems impossible, or it’s nothing. Carmenza Banguera. 125 cm x 90 cm. Acrylic on cotton paper (Hahnemühle). 2024.

[1] The Body in Colombia: State of the Art, Body and Subjectivity / Nina Alejandra Cabra A., Manuel Roberto Escobar C. — Bogotá: IESCO: IDEP, 2014. p. 54

[2] Janeth Blanco presented a new iteration of the work during the openings of both venues—an activation of the original performance first conceived in 1997.

[3] Yumbo, Valle del Cauca, is a Colombian municipality known as the “Industrial Capital of Colombia.” Located north of Cali, it is home to more than 2,000 companies, including factories, logistics centers, and free trade zones.