(Bandung, June 8, 1942 – Cuernavaca, Mexico, October 20, 2025)

By Yohanna Magdalene Roa

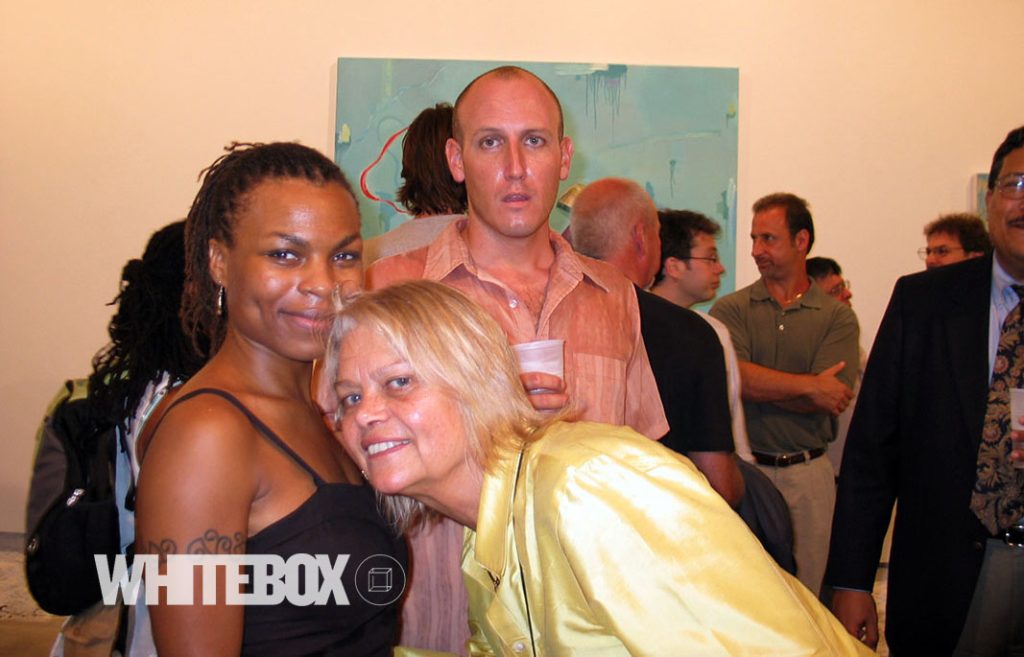

Carla Stellweg and Martha Wilson at WhiteBox, Spring Benefit 2012, New York City

Carla Stellweg (1942–2025) was an editor, curator, cultural manager, archivist, researcher, writer, essayist, professor, and art historian. Throughout six decades, she worked transdisciplinarily, moving between the museum, the gallery, the magazine, the classroom, and the archive, interweaving critical thought, curatorial practice, and cultural activism. A key figure in shaping Latin American and U.S. Latinx art within the international circuit, Stellweg understood art as a system of translation rather than a set of borders, a continuous conversation across territories, languages, and bodies.

I never met Carla Stellweg in person, yet her enigmatic and vital figure always seemed to embody a natural affinity for risk. My interest in her deepened while working on the process to create the WhiteBox Historical Archive, one of the projects I am currently dedicated to. In the process of organizing and cataloging this archive, I encountered her contributions to WhiteBox’s history—including the 2004 exhibition Domestic Arrivals, co-curated with Anat Ebgi. Through these materials, I came to recognize the breadth of her transnational engagement and her lasting influence on the institution’s curatorial identity. The photographs accompanying this essay all come from the WhiteBox Historical Archive, a testament to her sustained presence within the history of experimental art in New York.

Juan Puntes, WhiteBox director and Karla Stellweg. June 2012. WBX archive

I heard multiple stories about her, told in many tones. Some remembered her with admiration, others with ambivalence, but all agreed she possessed an energy that refused to be still. Across languages, countries, disciplines, and generations, she built bridges that allowed artists, ideas, and affections to circulate. If I had to choose an image, I would say that Carla lived her seven lives—the seven usually granted to those who cannot sit still—and she lived them all intensely.

1. Bandung: Birth in the “Outside”

Carla Margareta Stellweg was born in Bandung, then part of the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies. That first coordinate of a colonial zone in crisis marked her worldview: the sense of living in transit, of inhabiting instability. As she often repeated in interviews and classes, “One does not belong to a country, but to the conversations one sustains.” That awareness of displacement became the constant thread running through her biography and curatorial thinking.

2. Mexico: Institutional Apprenticeship

In 1958, her family emigrated to Mexico. Stellweg quickly integrated into Mexico City’s art scene and began her training under Fernando Gamboa, the great museum builder who helped define modern Mexican identity through exhibition-making. With Gamboa, she worked on international world fairs and pavilions—Expo 67 in Montreal, HemisFair 68 in San Antonio, the 1969 Venice Biennale, and Expo 70 in Osaka—acquiring an early mastery of the museographic devices that connect art, politics, and national representation.

In 1973, together with Gamboa, she founded Artes Visuales, published by the Museo de Arte Moderno. It was the first bilingual (Spanish–English) contemporary art magazine in Latin America. From 1973 to 1981, it became a unique editorial experiment—a critical platform introducing conceptual art, political thought, and feminist discourse into a still-conservative cultural sphere. Its eventual censorship by government officials closed a chapter of independence and marked the beginning of Carla’s move northward.

3. Feminism in a Transnational Key

In 1975, she organized the first seminar on women’s expression in art at the Museo de Arte Moderno. Her feminism was never doctrinaire: she practiced it as a strategy of dialogue rather than as an identity marker. She built alliances with militant groups, among them the Guerrilla Girls, while developing an early intercultural reflection on gender and representation. In the 1970s and 1980s, when feminism was still seen as foreign to debates on identity and postcoloniality, Stellweg re-territorialized it, turning it into a transborder way of thinking.

Her project was not to underline difference but to dismantle hierarchy: to connect the experience of a Mexican painter with that of a Chicana photographer or a European performance artist, regardless of passports. This feminism of translation, not of slogans anticipated, the debates that would later shape art discussion.

4. New York: Architect of Cultural Bridges

In 1982, Stellweg settled permanently in New York. Her arrival coincided with SoHo’s rise as a hub for alternative art and independent spaces. Within a year, she had fully entered the New York circuit—first as a gallerist (Stellweg-Séguy Gallery, 1983–85), then as chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MOCHA) (1986–89), and finally as founder of the Carla Stellweg Gallery (1989–97).

For more than three decades, her East Houston Street loft served as a meeting place for artists, curators, and thinkers from across the Americas. Critic Edward Sullivan once described it as “an unofficial Latin American embassy in Manhattan.” There gathered figures such as Ana Mendieta, Liliana Porter, and Luis Camnitzer, as well as emerging artists who found in Carla a mentor eager to translate their work into global contexts. Her gallery gave visibility to many women artists, including Magali Lara and Myra Landau, who were beginning to explore the body and identity as fields of resistance.

Her curatorial and advisory role was also instrumental in exhibitions such as The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970 (Bronx Museum, 1987) and Hispanic Art in the United States (1988), ensuring that these shows engaged with Latin America without folklorizing it.

In a field still structured by colonial hierarchies, Stellweg worked toward a horizontal vision of Latin American art. Unlike the anthology-driven approaches of the 1990s, she proposed a curatorship of transit art not as an identity block but as a field of exchange. She became one of the first mediators between Latin America and New York, an engineer of connections who opened institutional and discursive space for women artists long before the major museums did.

5. WhiteBox: Crossing Scenes

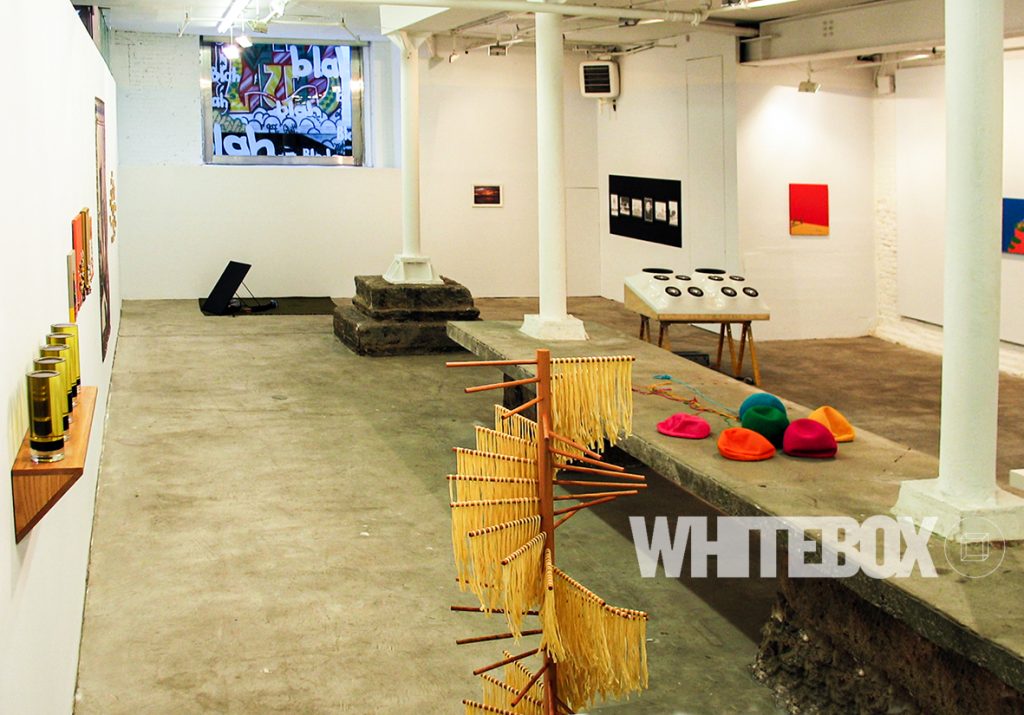

Images from the opening of the 2004 exhibition at WhiteBox, curated by Carla Stellweg and Anat Ebgi.WBX archive

Her relationship with WhiteBox lasted approximately 10 years, from 2003 to 2013 (with some interruptions), during which she served on the Board of Directors and as Director of Program Funding. In 2004, she co-curated, alongside Anat Ebgi, the exhibition Domestic Arrivals, the first in a series mapping regional art scenes through a global lens.

Dedicated to Miami-based artists, the exhibition explored how New York’s core influenced and was in turn influenced by South Florida’s cultural dynamics. The project epitomized Stellweg’s methodology: identify an active margin, make it visible at the center, and allow the exchange to transform both poles. Her curatorial vision anticipated what we now call intersectional curating: articulating distinct contexts without imposing hierarchies.

Carla Stellweg, opening of the 2004 exhibition at WhiteBox

6. Pedagogy and Archive

Between 2005 and 2022, Stellweg taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where her seminar What is Latin American & Latinx Art? became a landmark course. She never sought to answer the question but to keep it open. Her pedagogical method was itself a form of curating: crafting spaces of dialogue where artistic identities could collide and recombine.

Meanwhile, her personal archive, magazines, ephemera, mail art, correspondence, photographs, and catalogs were acquired by the MoMA and Stanford University Library. Her life’s work was celebrated at the Museo Tamayo (2023) with Cultivar. Homenaje a Carla Stellweg, curated by Pablo León de la Barra and Andrea Valencia. There, Carla witnessed her life become archive, her archive become art, and her art become living memory.

7. Cuernavaca: Return to the South

Her final years unfolded in Cuernavaca, surrounded by jacarandas and papers. From there, she continued advising projects and mentoring young artists and curators. Her death, on October 20, 2025, closed a vital cycle that had begun in another tropic yet never ceased to converse with New York.

Epilogue

In New York, I have spoken with artists she brought to exhibit in Mexico—Europeans, Asians, Latin Americans, and others she introduced to the New York scene. Carla was as demanding as she was unpredictable; her complex temperament cannot be separated from her work. She lived without the caution of those afraid to fall, and that is why her legacy remains unmistakable: she was part of a generation that helped build the cultural flow we now take for granted.

Latin America is read differently in New York than in Latin America, and Carla understood that nuance. She was, in the most profound sense, a New Yorker, not only for the years she lived there but for her capacity to inhabit the city as a web of translations. She knew how to mix territories. She lived her seven lives fully and wasted none of them. At times she defied them; at others she fractured them, but continuously, she inhabited them with unapologetic passion.

Carla Stellweg leaves behind a legacy of great magnitude, one that will require time, distance, and collective study to be fully processed. The complexity of her projects and the layered history of her life reveal not only her transdisciplinary work but also the deep political and aesthetic positions that guided her practice. Her story is not easily categorized: it unfolds across multiple territories, genders, and languages, tracing the contours of an art world she helped to invent and complicate in equal measure.

Her name remains linked to one enduring certainty: art has no center, only circulations, and only someone who has lived several lives could ever draw that map.

All photographs are copyrighted and belong to the WhiteBox NY Archive. They are reproduced here courtesy of WhiteBox New York.