An Exercise to Reconcile Ourselves with Our Bodies

By Blanca Meneses

Exhibition curated by Karen Cordero R. Tolzú Cultural Center in Toluca, México

Artists: Manuela Ballester, Angelina Beloff, Rocío Caballero, Carmen Chami, Olga Costa, Elvira Gascón, María Izquierdo, Mary Martín, Fanny Rabel, Josefa Sanromán, Lucinda Urrusti, Cordelia Urueta, Catalina Vallarta, Remedios Varo, Teresa Velázquez, Puri Yañez.

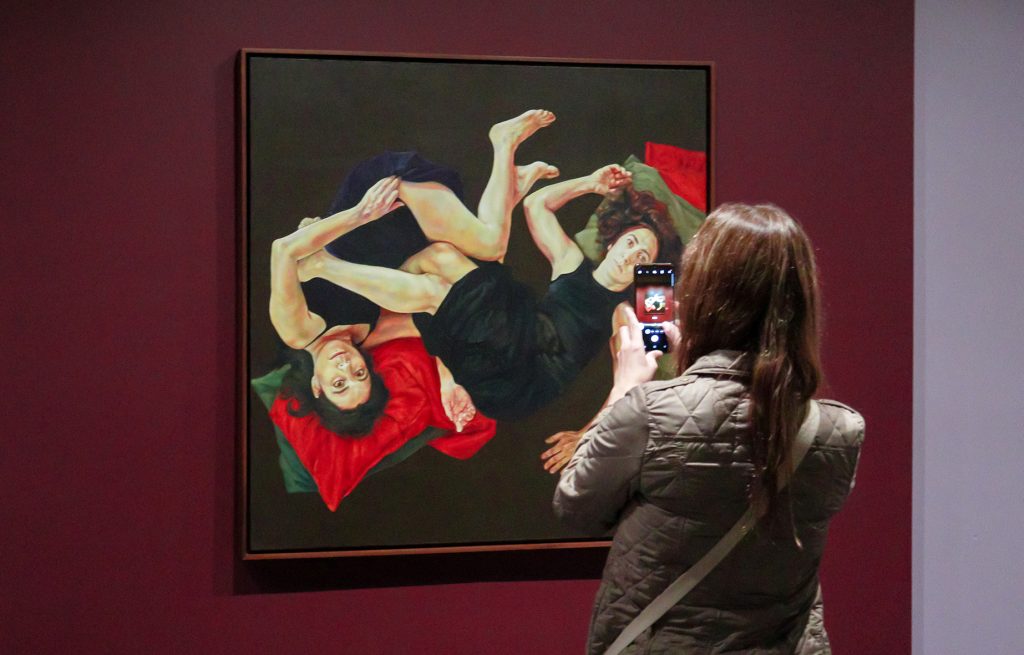

Exhibition view, Miradas femeninas al cuerpo desde la Colección Kaluz, (Feminine Gazes on the Body in The Kaluz Collection) Centro Tolzú, Toluca, Estado de México, 2024. Courtesy Centro Tolzú

Thinking about our bodies remains a challenging endeavor. When navigating bodily archives, we often prioritize their mechanistic aspects, overlooking the affective connections we have established with them since the beginning of our existence. Afro-American writer, activist, and founder of the digital platform The Body is Not an Apology, Sonya Renée Taylor, reminds us that bodies are not automobiles—or accessories—mass-produced with an expiration date approaching disposability, or simply what ceases to function normally.

Under this conceptualization, we are conditioned to despise our bodies. They become adversaries to conquer in an endless consumptive battle. Unfortunately, we forget that more than “machines,” bodies are spaces whose biological, historical, social, and cultural constructions are in constant flux and movement. By maintaining this dynamism, bodies hold the potential to express countercurrent forces capable of unraveling reflections on “difference, domination, and subversion” (Muñiz, 2014, p. 291).

Exhibition view, Miradas femeninas al cuerpo desde la Colección Kaluz, (Feminine Gazes on the Body in The Kaluz Collection) Centro Tolzú, Toluca, Estado de México, 2024. Courtesy Centro Tolzú

This triad of countercurrent forces unfolds in the exhibition Feminine Gazes on the Body in The Kaluz Collection, held at the Tolzú Cultural Center in Toluca and curated by art historian and critic Karen Cordero. The exhibition features 31 works by women artists, each of whom shares (or shared) a foundational connection to Mexico, whether as their birthplace or place of exile. Through paintings and drawings, these 16 artists offer representations of bodies that transcend the Cartesian order, which traditionally reinforces the separation between mind and body.

Across four thematic sections, the exhibition invites engagement with the creative, affective, and situated processes of the artists, aiming to embrace our bodies through lived experiences. The bodies represented by these women subvert hegemonic visual codes by re-signifying myths, exploring the value of emotions and humor, and incorporating diverse bodily practices, such as nudity.

In the first section, Deconstructing Myths and Stereotypes, curator Karen Cordero brings together artists whose works challenge classical representations of the female body. Here, the body is not reduced to an object of beauty, passivity, control, or eroticization. On the contrary, it is an affective force—liberated and moving transversely.

Image 1. Teresa Velázquez (Mexico City, n./b. 1962 )

Las tres Gracias (tríptico)/The Three Graces (triptych), 2020

Oil on wood. Dim. 27 x 36.2 cm/ 27 x 51.6 cm / 27 x 36.2 cm

Kaluz Collection.

To illustrate this, Mexican painter Teresa Velázquez (1962) challenges the myth of the Three Graces: the goddesses Aglaea, Euphrosyne, and Thalia abandon their divine destinies to become three friends who gather to create rituals, dances, and pacts amidst a rocky outcrop (Image 1). Their shadows—reflected in the landscape—depict the “here and now,” leaving an imprint of playful contemplation that occurs for them, not for the pleasure of others.

In this work, we perceive how the goddesses embody emotions that emerge from within the external world. Each one explores, touches, and senses her body; she observes herself without awaiting the voyeuristic gaze that typically constructs and evaluates.

The way in which these artists explore self-observation is closely linked to their portrayal of others, particularly through portraiture. The second section, Portrayals and Subjectivities, presents portraits of children, men, and women—mostly commissioned works but also preparatory studies of everyday individuals, such as the portraits by Spanish artist and exile Mary Martín (1927–1982).

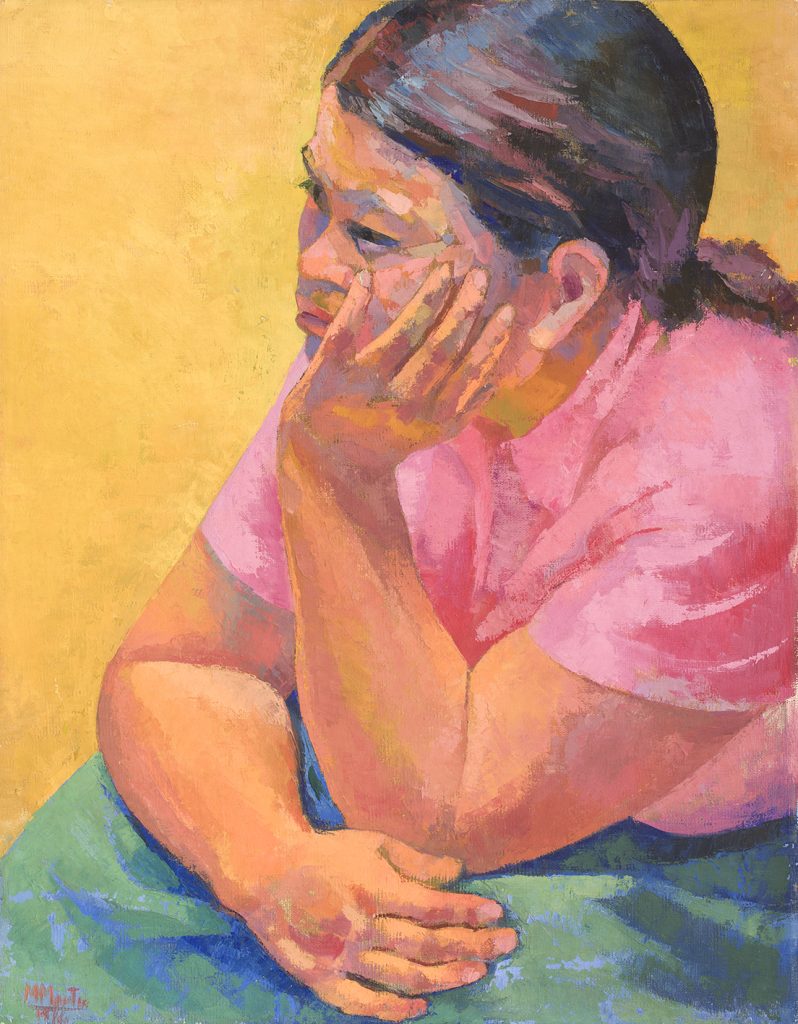

Image 2. Mary Martín (Salamanca, Spain, 1927 – Mexico City, 1983)

Anastasia, 1976. Oil on canvas. Dim: 84.8 x 71 cm. Kaluz Collection

Each brushstroke suggests the nature of the relationship the artists shared with the subjects portrayed, whether familial or friendly. In this section, Cordero underscores that the faces, clothing (e.g., shawls), spaces (both open and enclosed), body positions, and details in objects (e.g., chairs) accompanying the portraits highlight differences related to race and class, while particularly dignifying the individuality of each person (Image 2).

The third section, Bodies that Tell Stories, is a space that evokes bodies exploring various angles of movement and narrating fables, tales, and some fictional accounts. Like a cinematic sequence, each character creates a narrative that indirectly envelops us in the unfolding plot.

Image 3. Rocío Caballero (Azcapotzalco, Mexico City, n./b. 1964)

Fábula distópica para una tarde de verano/Dystopian Fable for a Summer Afternoon, 2018

Oil and acrylic on canvas. Dim: 100 x 80 cm. Kaluz Collection

This is exemplified in Dystopian Fable for a Summer Afternoon (2018), a work by Mexican painter Rocío Caballero, which critiques how capitalist systems insist on “adultifying” childhood to exert power over others (Image 3). Adult-centrism is conveyed through the figure of the “yuppie”[1] character, who forces a child to “crush” paper dolls placed on the floor while riding a bicycle. This act symbolizes the oppression of vulnerable bodies. The artist not only offers a sharp social critique of the power structures that affect the most vulnerable but also employs biting parody by animalizing her characters.

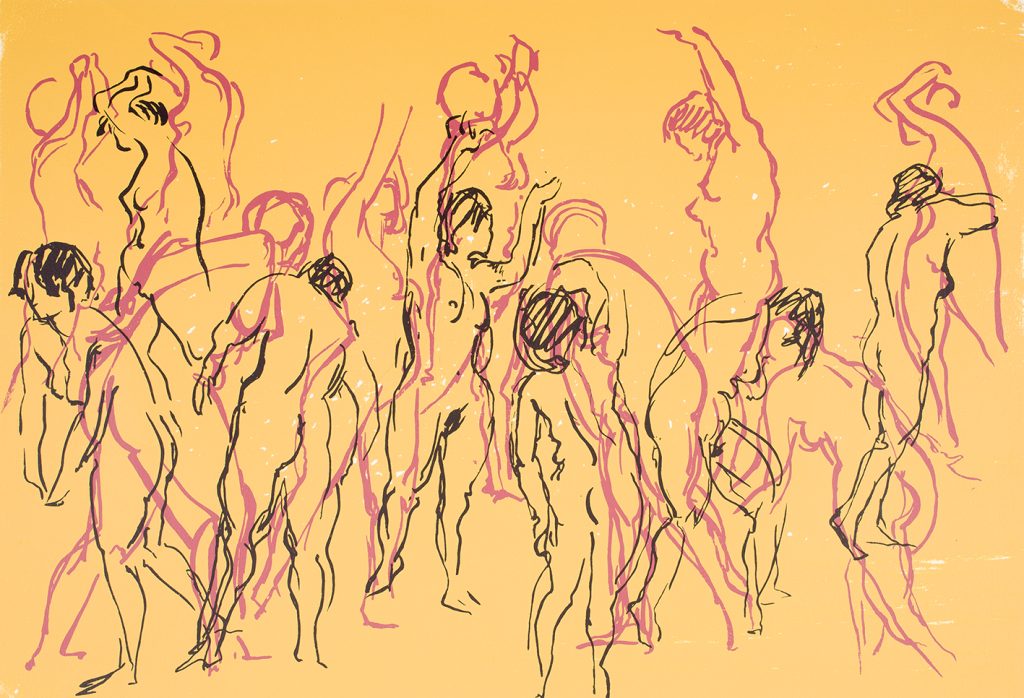

Image 4. Mary Martín (Salamanca, Spain, 1927 – Mexico City, 1983)

Yellow Movement, 1981

Screen print. Dim: 36.9 x 54 cm. Kaluz Collection

In the final section, Recreating Bodily Gestures, we encounter the nude. The women artists revolutionize this theme not only by appropriating it but also by presenting models of diverse bodies that subvert traditional representational canons. The nude, from the artists’ perspective, is not a subject governed by patriarchal power; rather, it is a diverse bodily existence that, instead of provoking shame, opens a space for questioning taboos (Image 4).

This journey—accompanied by a potent musical curation of 19th- and 20th-century female composers—offers transversal readings of bodies as texts that, as researcher Merri Torras points out, present grammars expressed in “movements, positions, displacements, and boundaries” (Torras, 2007, p. 27). It is evident that for the artists, there is no singular direction for interpretation. In fact, they propose autoethnographic narratives to create dialogues between personal and collective experiences. This encourages us to reflect persistently on the “body terrorism” (Taylor, 2019) we practice in our daily lives, which prevents us from developing strategies to empathize with bodily existence.

Exhibition view, Miradas femeninas al cuerpo desde la Colección Kaluz, (Feminine Gazes on the Body from the Kaluz Collection) Centro Tolzú, Toluca, Estado de México, 2024. Courtesy Centro Tolzú

References

García Múñiz, E. (2014). ¨Descifrar el cuerpo: Una metáfora para disipar las ansiedades contemporáneas¨. En A. García & O. Sabido (Coords.), Cuerpo y afectividad en la sociedad contemporánea: Algunas rutas del amor y la experiencia sensible en las ciencias sociales (pp. 271-300). Universidad Autónoma de México. México.

Muñiz, E. (2014). La diferencia, dominación y subversión. En A. García & O. Sabido (Coords.), Cuerpo y afectividad en la sociedad contemporánea: Algunas rutas del amor y la experiencia sensible en las ciencias sociales (pp. 291-300). Universidad Autónoma de México. México.

Taylor, S. R. (2019). El cuerpo no es una disculpa: El poder del autoamor radical. Melusina Editorial. España.

Torras, M. (2007). El delito del cuerpo. En M. Torras (Ed.), Cuerpo e identidad I (pp. 23-35). Edicions UAB. España.

[1] Yuppie is a term for young urban professionals in the 1980s who flaunted their upper and middle economic status through their clothing and luxurious acquisitions. The more purchasing power these characters had, the greater their desire to “crush” those they considered inferior.

Photo credits: Miradas femeninas al cuerpo desde la Colección Kaluz, (Feminine Gazes on the Body in The Kaluz Collection) Centro Tolzú, Toluca, Estado de México, 2024. Courtesy Centro Tolzú