Dedicated to Marie Blum

By Suzana Milevska

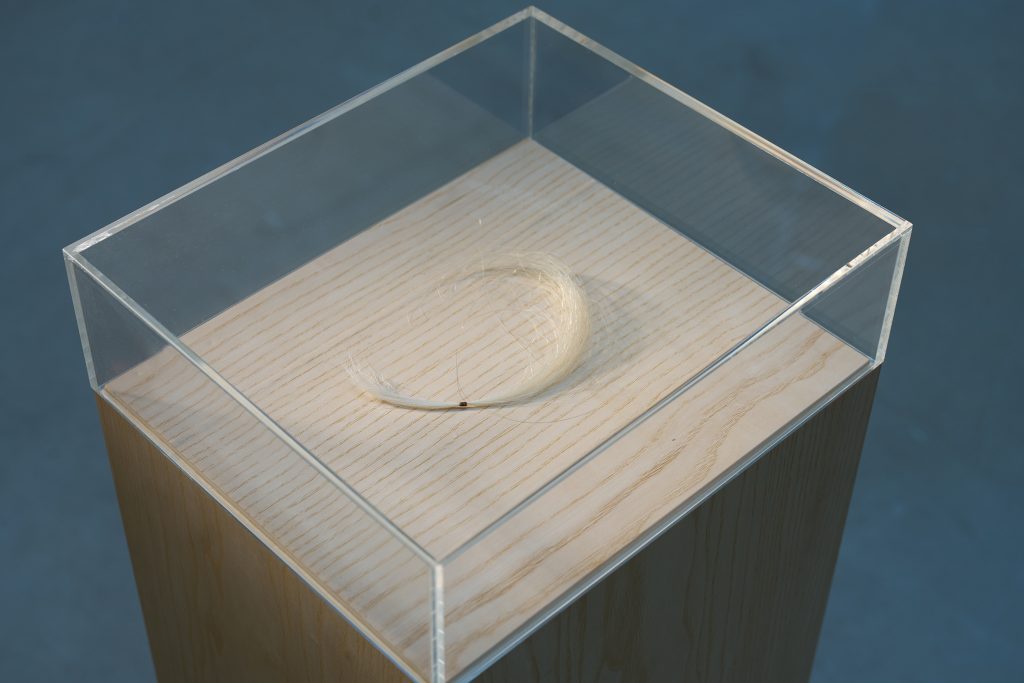

Strauß, E. Us, detail, 2024. Commissioned by TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol for Esther Strauß KINDESKINDER. Exhibition view, TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol, 2024. Photo: Günter Kresser.

I first met the artist Esther Strauß in May 2022, during the final week of my curatorial residency at the Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen in Innsbruck (2021-2022). I had dedicated my entire Fellowship research period to exploring the ethical and aesthetic protocols of apology, utilizing multiple artistic media, genres, methods, and strategies, including performative research, participatory art practices, and the renaming strategies that artists employ to address and investigate contentious histories. From our very first meeting, we realized that our past and current projects had a strong resonance with each other. We were unaware of each other’s work at the time, and it felt more than just a coincidence to discover that Esther’s Marie Blum project centered around her own renaming, while one of my major projects was titled The Renaming Machine (2008-2011). It was no surprise, then, that our collaboration continued long after my residency ended, manifesting in exhibitions and publications. However, we would never have met had it not been for the recommendation and insistence of the residency’s director and curator, Andrei Siclodi (1972-2025), who was well-versed in both our practices. His recent untimely passing last summer deeply saddened both of us.

S.M.

The first time I encountered your work Marie Blum, I was intrigued by its complex, research driven concept and structure. Could you share when and why you decided to embark on this particular project, dedicating yourself to the short life of Marie Blum, the Roma baby born and murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp?

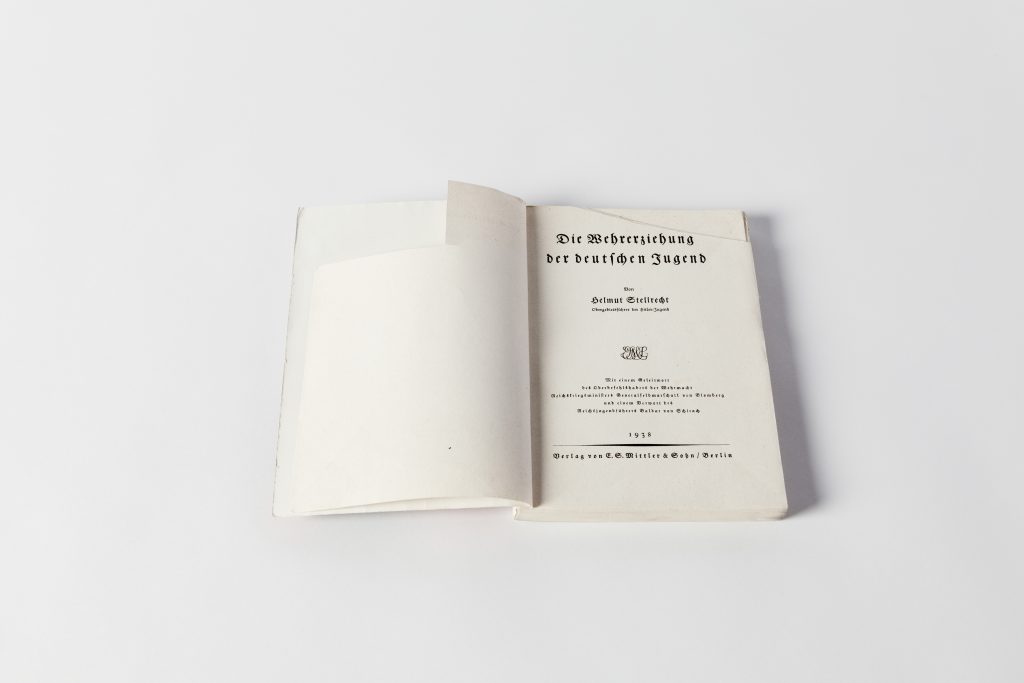

Strauß, E. Marie Blum, 2020. Photo: Robert Fleischanderl.

E.S.

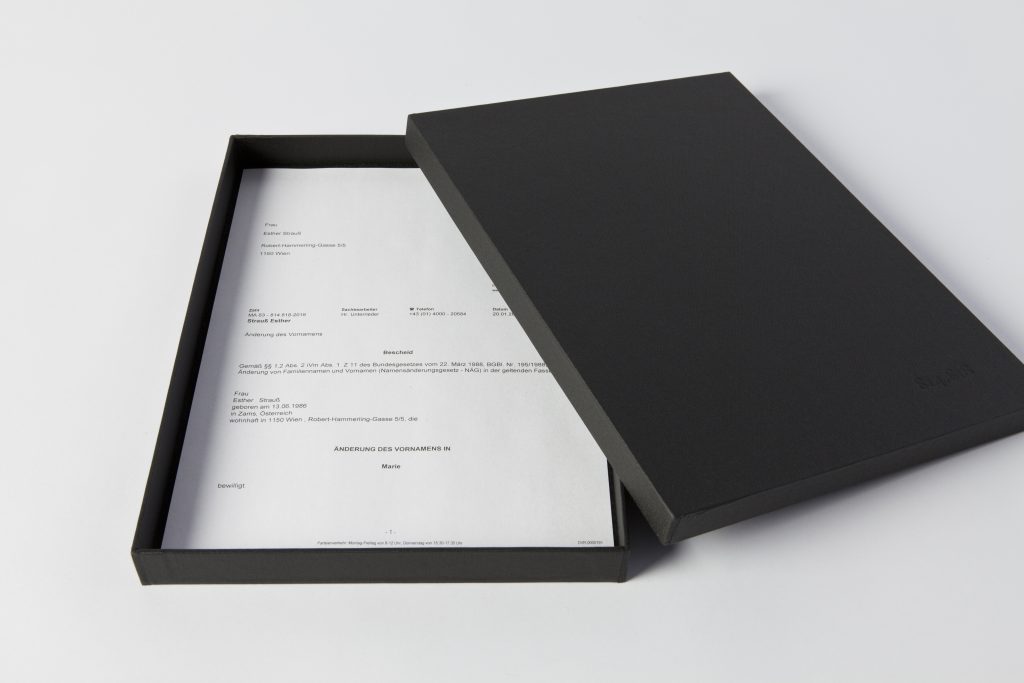

It all began with a poem. On January 27, 2019, I read a text by Rajko Djurić, a writer, philosopher, scientist, and Roma activist. His poem, Born in Auschwitz, Died in Auschwitz, lists the names of eleven children who were murdered on the same day they were born: Else Rebstock, Herbert Weiss, Joseph Straus, Anton Gross, Helena Kosak, Julius Horvath, Friedrich Krause, Theresa Schubert, Paula Zelinek, Lore Nachel, and Marie Blum. I couldn’t stop thinking about this poem. How do we remember children who had their entire lives taken from them? Who may have left no trace in this world other than their names? I began researching these children in various archives and discovered that Marie Blum was born on September 5, 1943, in Sector BIIe, the part of the camp where Rom:nja and Sinti:zze were interned. According to the central register, she was murdered three days later. Months later, I decided to create a performative monument for Marie Blum by giving up my own name for one year to adopt hers. Coincidentally, my legal name change was granted by the Viennese authorities on January 27, 2020, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Since then, I’ve been trying to understand the responsibility that comes with bearing Marie Blum’s name and telling her story. In this process, I realized that it was essential for me to let Marie Blum’s name interrogate my own. When I reclaimed my name after a year, it was legally unchanged. But for me, it was no longer the same. It had become as troubled as it should have been from the beginning.

S.M.

Would you elaborate on how this complex concept relates to your family background?

E.S.

Both my grandfathers volunteered as soldiers in the Wehrmacht, and one of my grandmothers worked as a typist for a Nazi organization overseeing the Hitler Jugend of Tyrol and Vorarlberg. When I asked my grandparents about their past as young adults, they never mentioned the people who were persecuted or murdered. It was as if their Nazi background had been separated from the crimes they committed, both in how they told their life stories and how they told them to me. I see this as a very Austrian phenomenon. Even when the Austrian government began building monuments to honor the persecuted and murdered, they continued to protect or even glorify the perpetrators, profiteers, and bystanders. This split, I think, allowed perpetrators and their descendants to disconnect their family’s history from history itself. To put it radically, even today, public monuments may offer descendants of perpetrators a remembrance of victims without acknowledging the perpetrators, in contrast, private monuments such as family photo albums, may provide a remembrance for perpetrators without recognizing the victims. For me, the performative monument dedicated to Marie Blum became a way to reconnect these fractured aspects of my family’s history. I visited archives to search for documents related to my relatives and publicly shared artwork based on the conflicts that emerged from my findings.

Blum, M. 2020, Granny, exhibition view, TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol. Photo: Günter Kresser.

S.M.

I’m also interested in the challenging effects your project had on your everyday life during and after the renaming process. Did you anticipate the intersections between your private life and your life as an artist that arose due to the personal and legal renaming?

E.S.

For me, performativity is about relinquishing control and entering uncertain territory. While I could anticipate some aspects of the project, I didn’t foresee how they would play out poetically and politically in my private and public life. When I applied for the name change, I was pregnant, so I knew that my child’s birth certificate would likely bear the name Marie Blum in the mother’s section. But I couldn’t predict that this shift would later lead to a work titled Privileges a lock of white hair I plucked from my head, which I tied with a strand of my brown hair, challenging the reality of people like me, whose historically charged names allow us to grow old comparatively unburdened. In contrast, the names of those who were innocently murdered have often faded. During the Samudaripen, the Nazi genocide of Rom:nja and Sinti:zze between 200,000 and 500,000 people were killed across Europe. Even 80 years after the war’s end, there is still no central memorial in Vienna for these victims, which is deeply disturbing. Their descendants, who should be among us today, are not. Why does this loss leave so few of us inconsolable?

S.M.

Aside from the central artistic strategies—auto-renaming and the performative monument—what other outputs have emerged from the Marie Blum project? I’m particularly interested in hearing about other concrete artworks, as well as the artistic genres and media you’ve used in the process of realizing Marie Blum.

E.S.

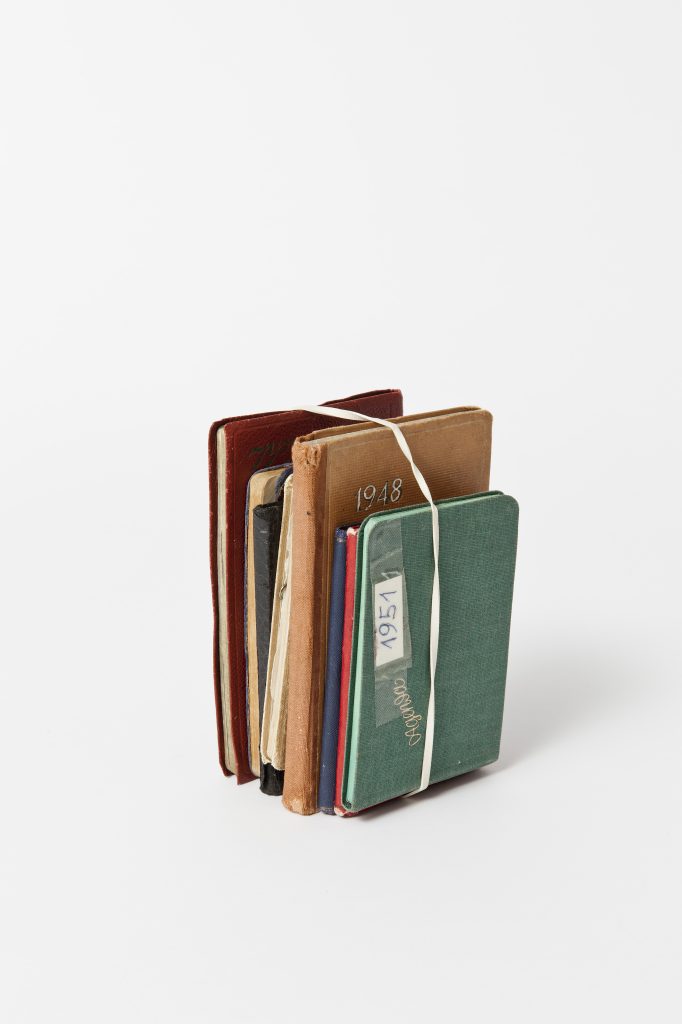

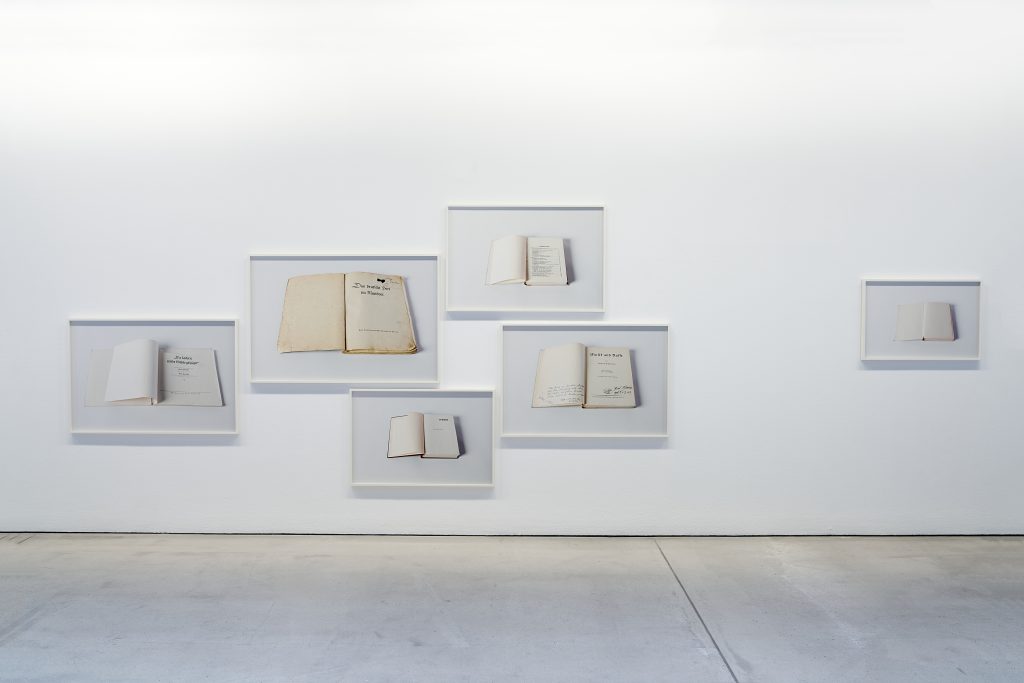

Over the last six years, I’ve worked with performance, photography, text, and objects. For example, the piece “Granny” involves 82 pocket calendars that my grandmother used as diaries, which she left behind in her bedroom when she died at the age of 95. I selected one of these calendars and added an entry in my grandmother’s handwriting without revealing which one was a forgery. Several years before creating the performative monument for Marie Blum, I asked my grandmother if she had been an NSDAP member; she said no. Yet, when I researched the German Federal Archives, I discovered she had indeed been a member. By adding one forged entry to her diaries, I challenge the credibility of all her other entries. “To critically examine Nazi history in one’s family, it may be necessary to question what you have been told, or not told. Far too often, names of family members are being protected when it comes to perpetratorship, a phenomenon which I discuss in Us, a series of photos of national socialist books which were gifted to the Tyrolean state museums after the names of the original owners were removed or blacked out, possibly by descendants.”

Blum, M. Privileges, 2020 – 2024, Esther Strauß, 2020–2024. Commissioned by

TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol for Esther Strauß KINDESKINDER. Exhibition view,

TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol, 2024. Photo: Günter Kresser.

Research at the Federal Archives in Berlin is surprisingly straightforward. The archive holds 12.7 million NSDAP membership cards, as well as personnel records for SA and SS members, among other documents. Anyone wishing to check the membership status of a relative can email the archive with the relative’s name, birth and death dates, and a completed form. For a small fee, historians working there will send you the results after a few weeks or months. This raises the question: Why is this kind of research still the exception in Austria? For my recent solo exhibition at TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol, curated by Nina Tabassomi, I developed a participatory installation titled “Do you want to know?”, which consists of a pallet full of forms from the Federal Archives that the audience is invited to take home.

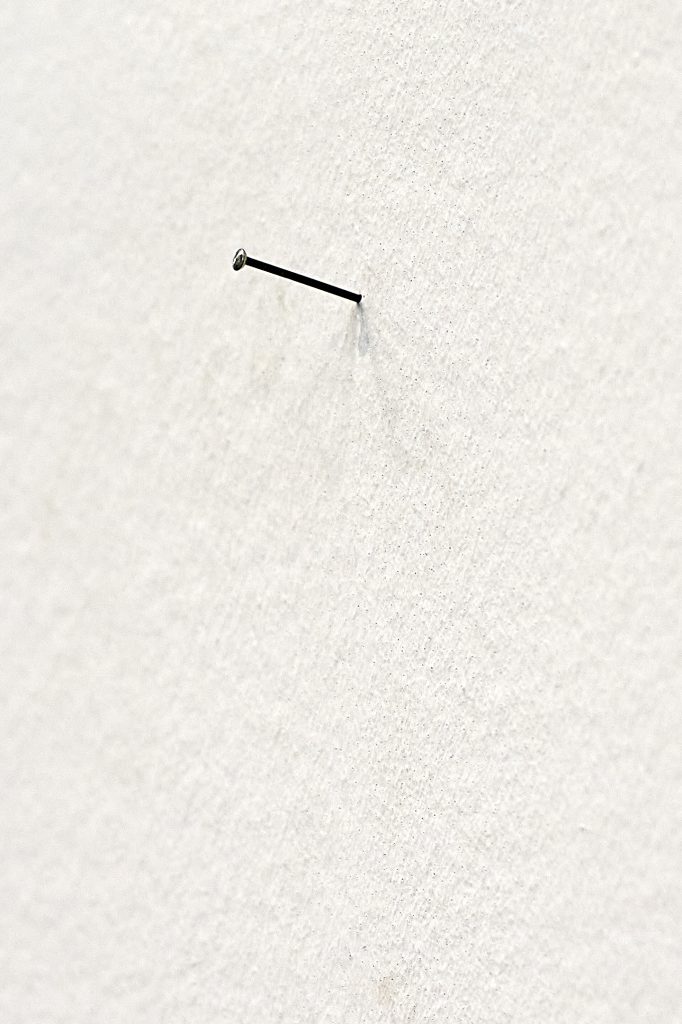

Other works in the project explore institutional responsibility. In one, I drove a nail into a wall at the TAXISPALAIS exhibition space, where it remained for three and a half months as a reminder of artworks stolen by the Nazis. After the exhibition closed, I offered the nail to the Tyrolean State Museums as a gift. The piece can only be exhibited on one condition: that the nail be used to hang looted art from the museum’s collection that has yet to be returned.

S.M.

Recently, you edited and published the book Marie Blum. It’s not a traditional catalogue; rather, it consists of interviews with various professionals whose work deals with issues related to Marie Blum’s fate, such as National Socialism, Samudaripen, the Holocaust, monuments, and renaming. Why did you prioritize interviews over images or theoretical texts about your work?

E.S.

The heart of most monuments is a sculptural structure. In my case, it’s not a stone, but a person bearing Marie Blum’s name. Since the monument is performative, it is allowed to grow, learn, and change over time—hopefully, for decades. When I chose to give up my name, I took on a responsibility that I must continually reevaluate. Part of this responsibility is acknowledging that, coming from a family with perpetrators, profiteers, and bystanders, the language I grew up with—and the silence that accompanied it—was inadequate, as it concealed or perpetuated violence. As I worked to unlearn this language while the performative monument expanded, I became interested in conducting interviews, as the answers I gave to certain questions were constantly evolving. One crucial lesson for me was learning to say, “What my grandparents did was wrong,” and leaving it at that, without adding a “but” or justifying the circumstances of their actions. But just as important is understanding my own mistakes and blind spots. I believe this monument is unique in that I can never be sure whether I am doing it justice. And I think that’s a good thing. A name is something deeply personal. It’s not the person who bears it, but it’s perhaps the closest thing to her.

Strauß, E. Us,2024. Commissioned by TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol for Esther Strauß KINDESKINDER. Exhibition view, TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol. Photo: Günter Kresser.

S.M.

How do you see the relevance of your project in today’s socio-political climate, particularly in Austria?

E.S.

In many Austrian families, there has been little or no critical reflection on the actions of family members who were perpetrators, profiteers, or collaborators. Today, when right-wing politicians excuse or even glorify Nazi perpetrators, they indirectly absolve the ancestors of some of their voters, which makes their politics appealing. What’s alarming today is the lack of knowledge among many Austrians about the structures protecting democracy. That’s why right-wing parties are applauded for trying to replace the Haushaltsabgabe—a small mandatory monthly fee every household pays to fund independent public broadcasting—with direct government funding, which would make public journalism more vulnerable. There’s also little awareness of the democratic value of artistic freedom, which has been protected by the Austrian constitution since 1982. I am currently working on pieces that aim to address and change this.

Strauß, E. The gift, 2024. Commissioned by TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol for Esther Strauß KINDESKINDER. Exhibition view, TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol, Photo: Günter Kresser

S.M.

Do you see a connection between the rise of the far-right and anti-gender discourses? Do you think chauvinist and patriarchal attitudes in Austria were less prominent in the 1990s and early 2000s?

E.S.

Austrian right-wing and far-right parties have always been anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQIA+. This hasn’t changed, but their popularity has. In the 2024 national elections, the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) became the party with the most votes, securing 28.85% of the total. The FPÖ prides itself on placing freedom at the heart of its name, but their politics raise the question: Whose freedom? According to them and their allies, universal human rights only apply to some. If we’ve learned anything from National Socialist dictatorship and the war of aggression and annihilation, it’s that if we allow ourselves to be divided in this way, the freedom of all of us will be at risk.

Strauß, E. Do you want to know? 2024. Commissioned by TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol for Esther Strauß KINDESKINDER. Exhibition view, TAXISPALAIS Kunsthalle Tirol, 2024. Photo: Günter Kresser.

Esther Strauß (b. 1986) is a performance artist whose work engages with performative monuments, gaps, and ritual design. In her first performance, Strauß offers a 15-minute hand-in-hand walk via newspaper advertisement. In 2015, she slept and dreamed on Anna Freud’s psychoanalytic couch at the Freud Museum in London, hugging a doll that resembled her. In 2024, she exhibited a statue of Mary giving birth, titled crowning, in the art space of an Austrian church. She has received numerous awards, most recently the RLB Art Award in 2024, and has exhibited internationally. Strauß has taught art writing at the University of Arts Linz since 2015. www.estherstrauss.info