By Yohanna M. Roa

The power of textiles, prick them with the needle.

Some time ago, during a talk about my textile art practice, another panelist, a scholar, asked me how I experienced the embroidery process in my studio. “Meditatively,” she suggested, imagining a space of retreat, silence, and contemplation. I responded that, while I deeply respect those who, like me, spend hours in front of a piece of fabric, I do not consider embroidery to be a passive act, much less a “quiet” one. On the contrary, I see textile work as a space of rebellion, of re-existence, a vital response to the systemic violence that has crossed, invaded, and disciplined our bodies and our voices.

Historically, textiles have been both a technology and a language, serving as a tool for subsistence and as an archive of memory. It has taken part in processes of civilization, cultural exchange, resistance, and war. However, from colonization to the most recent dictatorships, textile work has been understood, to a great extent, as “feminine” work, that is, subordinate, private, and far removed from the political and intellectual spheres, not as an accident, but as a construction that has sought to conceal its transformative power.

And throughout, it has also been a tool of battle.

I neither focus on categorizing textiles as either art or craft, nor do I wish to fall into the dichotomy of the “popular” versus the “intellectual.” This work has already been developed by numerous thinkers, among them Rozsika Parker, who, in The Subversive Stitch1, analyzes how embroidery has historically occupied an ambivalent space: domesticated and controlled by patriarchy, yet subversive, intimate, and capable of expressing resistance from within the private sphere. My approach is different: I frame textile as a field of power, as a situated practice that rebels through the body, reveals structures, builds community, and sustains. Because what is sustained is also defended.

As a teenager, I was harassed by a man on a city bus. I came home upset and told my mother, an executive with no real ties to textiles. To my surprise, she said the same had happened to her. Back then, she took a needle from my grandmother’s workshop, my grandmother was a lifelong seamstress, and stabbed it into a rubber eraser. She carried it with her after that, a tool, a weapon. “If a man came too close, I pricked him,” she said. That needle, so small, provoked screams and drove aggressors away. For years, I carried that needle with me. It stopped accompanying me when I began to train in martial arts, but I never ceased telling that story. Some people ask me how my mother could have taught me “something so violent.” Thus, I ask myself, why does that needle seem to be more violent to them than the harassment itself? That confirmed for me that the needle has power, to such a degree that those in positions of power fear it.

Three ways to confront violence through the textile.

From diverse geographies and historical contexts, textiles have been tools of struggle, not passive or decorative elements, but active, combative, and profoundly political ones. The following four experiences, in Mexico, Chile, Greece and NYC, allow us to trace a line of continuity around how practices traditionally considered feminine and non-intellectual, such as embroidery or sewing, become devices of collective resistance, of an archive of memory, and of confrontation with patriarchal, state, and symbolic powert structures: the Chilean arpilleras, Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria, an initiative that began in Mexico, and Neighborhood Guilt, a work recently exhibited at the Greek Consulate in New York City.

Chilean arpilleras, memory embroidered under a dictatorship

During Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship (1973–1989), arpilleras emerged as a political medium of collective denunciation. Made with scraps of cloth, threads, and crocheted edges, they depicted scenes of daily life under a regime of repression, censorship, and structural violence. Although their appearance could seem naive, their content was radical, hinting at disappearances, detentions, poverty, and injustice. They were cries embroidered by the hands of those who could not cry out with their own voices.

Left: Anonymous. Remembering Salvador Allende, n.d. Embroidered textile, 38 x 48 cm.

Right: Arpilleristas E.M. and F.D.D., The Coup, 1986. Embroidered textile, 38 x 50 cm. Courtesy of Francisco Letelier and Isabel Morel Letelier to the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA). Exhibited in Arpilleras de Chile (Museum of Latin American Art, 2019–2020). Images available at: https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-sept-112

The production of these pieces was collective; women organized in community workshops, many linked to parishes or human rights centers, shared materials, knowledge, and above all, experiences of pain and survival. In that context, the act of sewing became a gesture of resistance, of shared mourning, and of denunciation. The textile, historically relegated to the domestic and feminized sphere, was re-signified as a tool of political action.

The circulation of the arpilleras, in the face of the regime’s censorship, was also a collective strategy; many were taken clandestinely out of Chile and distributed at street fairs, international events, and solidarity networks. They functioned as visual denunciations of human rights violations and as tangible ties between local and global struggles. Although in many cases the women were not imprisoned directly, they were surveilled, interrogated, and threatened. Some were temporarily detained. Their roles as mothers, widows, or relatives of the disappeared granted them a moral legitimacy that challenged the State’s narrative. Still, the threat was ever-present, and stitching an arpillera became an act of courage. In these pieces, ornament and decoration become archive, trench, and outcry all at once.

“Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria,” (¨Embroidering for Peace and Memory¨), a textile intervention in the face of violence in Mexico.

March on September 26, 2015, marking one year since the disappearance of the students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Guerrero. Photograph by a member of Fuentes Rojas Colective.

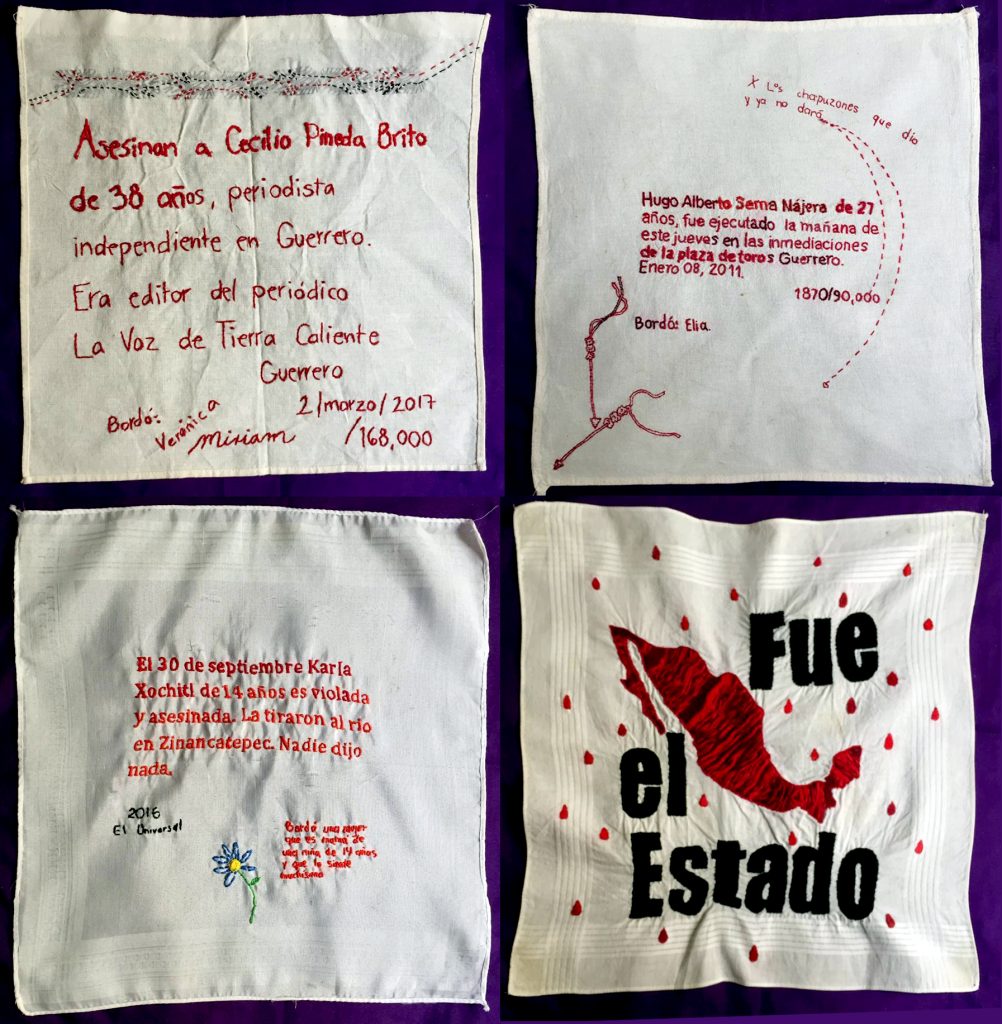

In the context of generalized violence in Mexico, the movement ¨Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria¨ emerged in 2011 as a reaction to the murder of the poet Javier Sicilia’s son3. His personal pain transformed into a public demand to create commemorative plaques for the victims. However, one member of the collective ¨Fuentes Rojas¨ proposed a more sensitive and powerful alternative: to embroider white handkerchiefs with the names, dates, and places of people who were killed or disappeared. The action, inspired by the work of an Oaxacan artist who intervened in newspaper front pages, soon became an expansive and replicable practice.

Embroidery became a public act, a tool for processing grief, collectivizing memory, and confronting institutional silence. The meetings began as small, private gatherings, but after a call in the Zócalo of Mexico City, the massive participation drove the decision to take the public space. The cells of this collective began to multiply in different cities and states, and thanks to digital platforms, the movement reached national scale.

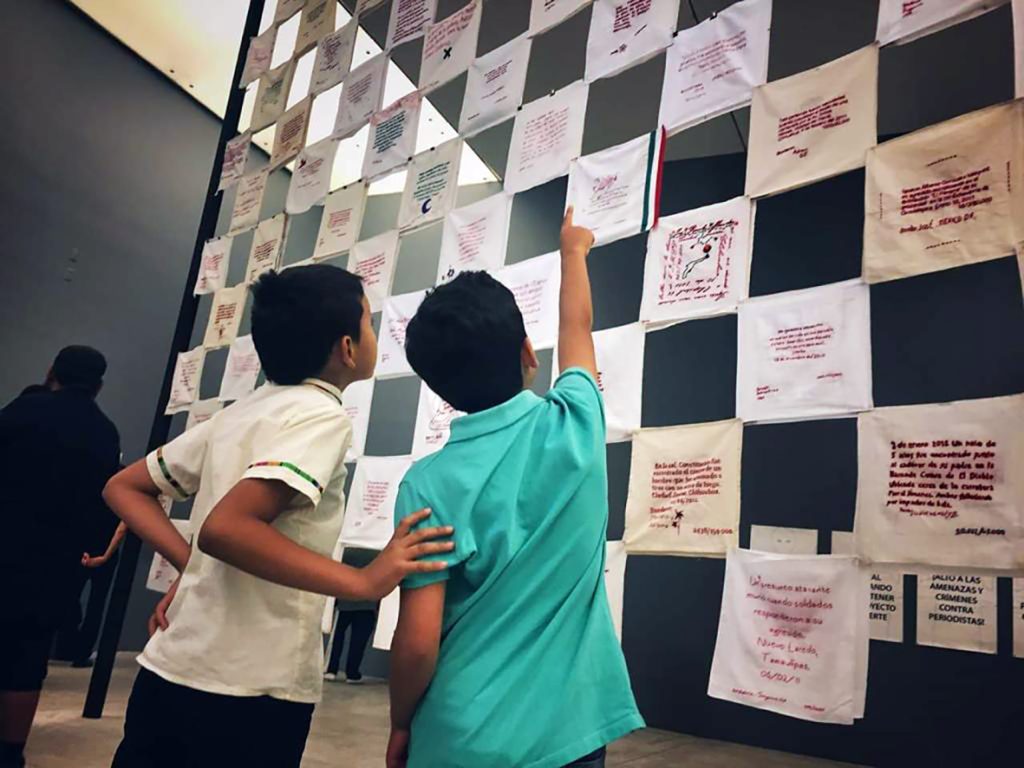

Photograph from the exhibition #NoMeCansaré, held at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in 2018. Photo by Mariana Barreiro.

On December 1, 2012, the collective organized a large-scale installation in Mexico City, the capital. Hundreds of handkerchiefs embroidered with red thread would form a civic mural: a textile narrative documenting the scale of the violence. Beaucause the city government was reluctant to allow such a vast installation, bearing the names of the victims of violence to be installed at all, it relocated the installation from the Zócalo4 (the main square at the city’s center) to Alameda Central, and later again to the vicinity of the Museum of Memory and Tolerance under the pretext of renovation work, yet the collective managed to install it partially.

The scene was deeply moving: the handkerchiefs stretched across several city blocks, while more kept arriving from every corner of the country.

Details of four embroidered handkerchiefs, currently kept in custody.

A security operation unleashed unexpected chaos: explosions, riots, a heavy police presence, and Molotov cocktails. There was provocation and harassment directed at participants. Several members of the collective took refuge inside the museum, and many others, alongside street vendors and neighbors, rolled up the scarves into a massive textile ball nearly six feet in diameter.

The incident marked not only a rupture in the installation but also internal fractures within the collective. The repression sent a clear message: embroidery unsettles, denounces, and above all, brings to light what others seek to keep hidden.

“Neighborhood Guilt,” the flag questioned through textiles.

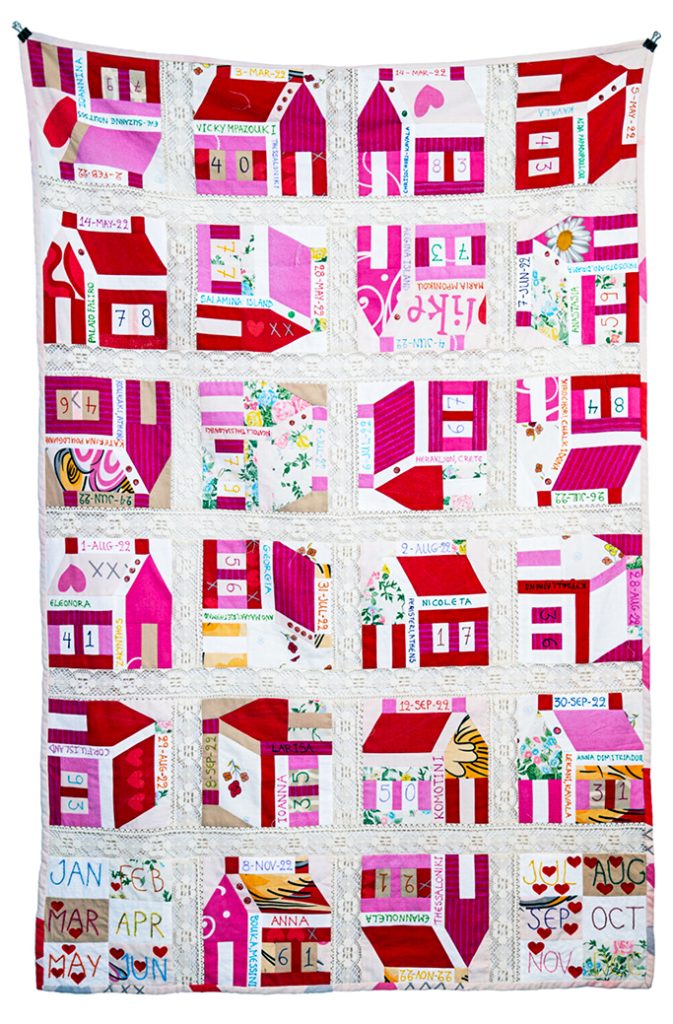

On December 15, 2023, Neighborhood Guilt opened, an exhibition curated by The Carte Blanche Project, at the Greek Consulate in New York. Two works by the artist Georgia Lale, Flag (63″x109″) and Neighborhood Guilt (57″x38″) were presented as part of the project. Both pieces were made with used sheets donated by Greek women as a symbol of resistance and denunciation of gender violence.

Left: Georgia Lale. (2023). Neighborhood Guilt [Donated bedsheets, sewing thread, and fabric ink, 145 × 97 cm]. Right: Georgia Lale. (2021). Flag [Bedsheets donated by women living in Greece and sewing thread, 160 × 277 cm]. Courtesy of the artist.

The flag retains the original composition of the Greek flag, but replaces its blue and white with shades of pink, magenta, and red. On the floral and domestic patterns of the embroidered sheets, the national symbol is redefined as a feminine flag, marked by the blood of murdered women. In Neighborhood Guilt, the geometric figure of a house is repeated, and inside each one, the name and date of a woman victim of femicide, killed in her own home, is embroidered.

At the Consulate General of Greece in New York, artist Georgia Lale pictured the works before and after censorship, including Neighborhood Guilt and Flag. Courtesy of the artist.

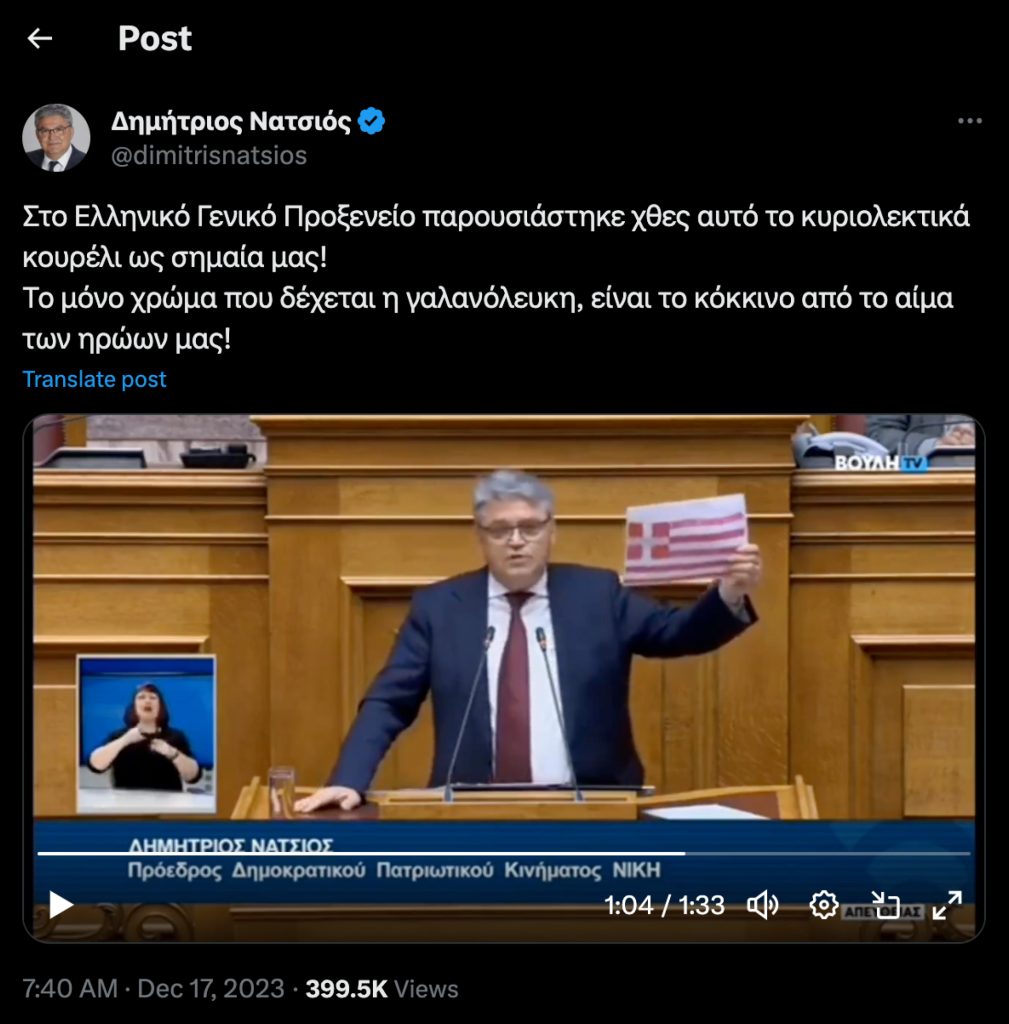

The institutional response arrived quickly. A day after the opening, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Greece, George Gerapetritis, posted on his X profile, “Yesterday, the Consulate General of Greece exhibited this rug as our flag! The only color that can replace the blue and white of the flag is the blood of the nation’s heroes.” To which the artist publicly responded, “Victims of femicide and domestic violence are heroes of the fight for freedom and life in Greece and internationally.” Three days after the opening, the works were censored, one removed from the room, the other returned folded in a plastic bag.

Left: Coverage by the Greek press of the incident. Right: Excerpt from the speech delivered by Member of Parliament Dimitris Natsios in the Hellenic Parliament (December 16, 2023). His post on X reads: “Yesterday, the Consulate General of Greece displayed this carpet as our flag. The only color that can replace the blue and white of our flag is the blood of the nation’s heroes.” This statement was also referenced by Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs George Gerapetritis on December 18, 2023—courtesy of the artist.

The minister’s reaction reveals two tensions: on the one hand, the opposition between victims of femicide and “national heroes,” and on the other, the defense of a national symbol over the lives and memory of murdered women. The flag, as a representation of the nation, seems reserved for bodies that can wield weapons, not for those who resist in the intimacy of the home or on the margins. The gesture of censorship lets us glimpse the discomfort produced by the appropriation of national symbols by artists who make gendered violence visible. The personal, in this case, is not only political, it is political and public.

The three experiences I have presented, the Chilean arpilleras, the community installation of “Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria” in Mexico, and the censorship of Georgia Lale’s work in New York, are not isolated or exceptional events. They are part of a broader genealogy of textile practices as forms of re-existence in the face of structural violence, silencing, and institutional denial. Throughout the world, feminized bodies have taken the thread and needle not only as tools of creation, but also of political action. The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina redefined the white handkerchief as a textile symbol of justice. The CoMadres in El Salvador embroidered quilts with the names of their relatives who disappeared during the war. In Palestine, tatreez has become a trench of identity in the face of occupation. In Bosnia, the women of Srebrenica embroidered the names of the victims of genocide on white cloths hung in public. In Afghanistan, South Africa, and the Pacific Islands, artists and communities have also woven their resistances. Each stitch, whether on a domestic sheet, an embroidered flag, or a handkerchief, reveals that textiles are a living archive — an intimate and collective battlefield — where the act of sewing becomes political and performative.

The three experiences —the Chilean arpilleras, the community installation of “Bordando por la Paz y la Memoria” in Mexico, and the censorship of Georgia Lale’s works in New York — are not isolated or exceptional events. They are part of a broader genealogy of textile practices as forms of re-existence in the face of structural violence, silencing, and institutional denial. Throughout the world, feminized bodies have taken the thread and needle not only as tools of creation, but also of political action. The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina redefined the white handkerchief as a textile symbol of justice. The CoMadres in El Salvador embroidered quilts with the names of their relatives who disappeared during the war. In Palestine, tatreez has become a trench of identity in the face of occupation. In Bosnia, the women of Srebrenica embroidered the names of the victims of genocide on white cloths hung in public. In Afghanistan, South Africa, Uganda, the Pacific Islands, and other geographies, artists and communities have also woven their resistances. Each stitch, whether on a domestic sheet, an intervened flag, or an embroidered handkerchief, reveals that textiles are a living archive, an intimate and collective battlefield, where the act of sewing becomes political, performative, and profoundly embodied.

It is no accident that many of these works have unleashed institutional censorship, police repression, or state surveillance. What is woven is feared. The needle as a weapon, embroidery as a subversive archive, the textile as a language that is not domesticated. In all these cases, those in power have tried to render invisible, discredit, or directly destroy these uncomfortable materialities. The fear is not in the cloth, but in what it reveals: bodies that do not surrender, stories that are not erased, denunciations that do not fit within official discourse. Textiles, when activated as a collective gesture, not only state, but also challenge, and that is their danger, because they embody what is meant to be silenced.

That is why we need to critically and historically review the place assigned to textiles. We have been taught to think of it as a pastime. But the truth is that as technology, textiles radically transformed our ways of inhabiting the world. In the Neolithic, its invention allowed new structures of community, shelter, mobility, and ritual. The Industrial Revolution began and was sustained by textile machinery, and with it, the massive and precarious incorporation of women into waged labor. If we look closely, each of these transformative milestones in human history has textiles as a hidden protagonist. So then, what have we overlooked? Not only its aesthetic power, which in itself already merits an urgent rereading in hegemonic art histories, but also its political, technological, and revolutionary dimension.

Textiles are not just surfaces. They are devices of memory, of struggle, of collective construction. They are technologies of existence. Just as fire, carved stone, or steel marked epochs, the needle and thread also traced ruptures. It is time to recognize that when we speak of revolutions, it is not enough to look at weapons; we must also look at the hands that embroider. And ask ourselves why, even today, that remains so uncomfortable.

Just as I carried for years a needle hidden in an eraser, an inheritance of my mother’s self-defense strategy against harassment, many women have embroidered their grief, their fury, and their dignity. And as repression in Mexico, censorship in New York, and surveillance in Chile show, even a needle can put a dictator in check.

- Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. Women’s Press, 1984. ↩︎

- Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), Arpilleras de Chile, 2019–2020, accessed October 1, 2025, https://molaa.org/arpilleras-online-sept-11. ↩︎

- After the 2011 murder of his son by members of the Pacífico Sur cartel, poet Javier Sicilia led nationwide protests against Mexico’s Drug War. The movement, marked by the cry “¡Estamos hasta la madre!” (“We have had it!”), called for demilitarization, drug reform, and government accountability. On May 5, a national march began in Cuernavaca and ended in Mexico City with over 200,000 participants. Sicilia demanded the removal of the public security chief and presented a six-point peace pact. Protests also took place in dozens of cities across Mexico and abroad.. ↩︎

- The Zócalo of Mexico City is the Plaza de la Constitución, the largest public square in Mexico and the historic heart of the city since pre-Hispanic times. It is a key political and cultural site, home to the Metropolitan Cathedral and the National Palace, and a stage for major civic events, cultural celebrations, and protests. ↩︎