In-person interview with Jim Amaral. Casa Amaral, Bogotá, May 21, 2025.

By Daniel Santiago Salguero.

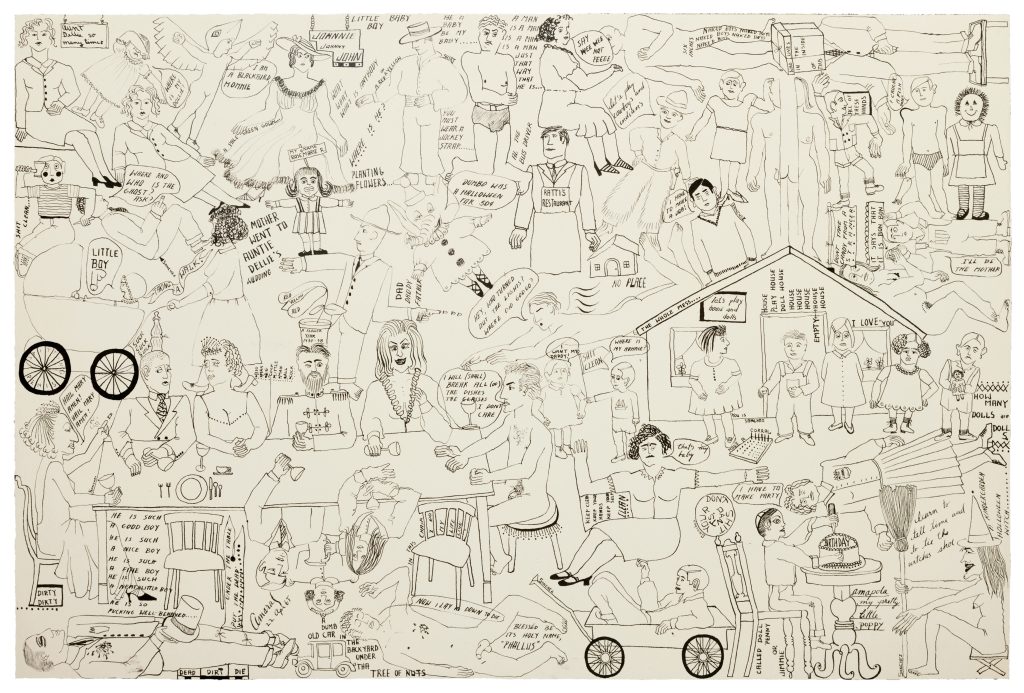

Jim Amaral. Walnut Tree (Árbol de Nueces), 36 x 54 cm. Pencil and ink on paper. 1965. Photo courtesy of the artist

Daniel Santiago Salguero (DSS) Master Jim, the column is partly about how artists narrate themselves. Could you speak to that in terms of your journey? You may start wherever you wish and go on as long as you like.

Jim Amaral (JA) I “It is tough.”

What I do is so varied in terms of media and scale. Sometimes, I think I’m a schizophrenic artist because, if you look at the different forms of my work, it seems like there are many personalities. And I do believe I have multiple personalities (he says this half-laughing, half-serious).

I grew up in a very humble town in California. I had almost no friends; there were not many kids my age around. Later, by some miracle, I got into Stanford University. My father, being an immigrant, was very committed to having professional children, so I started in medicine and quickly felt like a failure. After that, I tried architecture and then drawing; I did not know what it was or how to get where I wanted to, and honestly, I still do not.

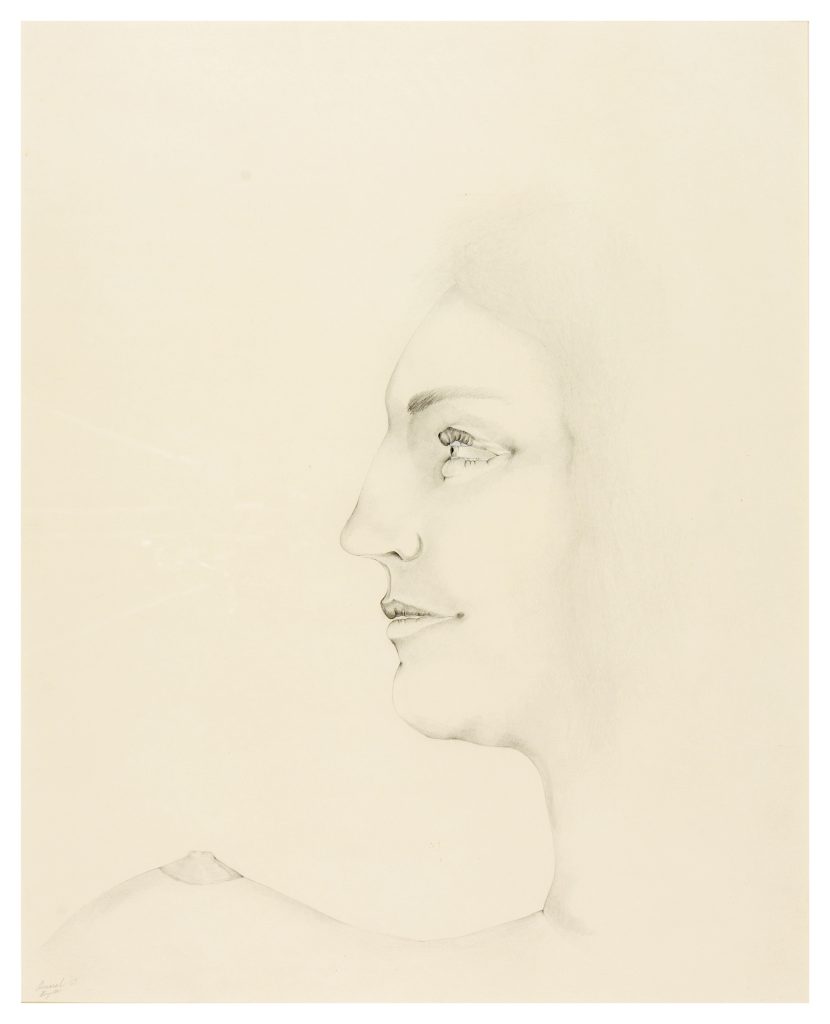

I was a terrible student. I started creating cartoons at Stanford, which marked the beginning of my path to drawing. Later on, already in Colombia, I saw a drawing magazine that belonged to a friend and thought I should try something more “artistic.” I created a few drawings and exhibited them at the Buchholz bookstore in downtown Bogotá, a very well-known establishment among intellectuals, bohemians, artists, and writers at the time. One of the drawings was of Isabella d’Este. I was interested in her both as a woman and as a patron of the arts.

Jim Amaral. Isabella D´Este N.1, 49×40 cm. Pencil on paper. 1969. Photographs courtesy of the artist

DSS: Maestro Jim, what do you think of Leonardo? At first glance, there seems to be some influence, your understanding of human anatomy, at once so animalistic and scientific, the way you use drawing to explore everything from design to machinery… and then there is that prolific output and the long life you both share. Would you say you relate to him?

JA: I saw Leonardo’s works in Paris when I lived there. I liked them a lot, but I was never obsessed with him.

I visited the Louvre to see the original Ritratto di Isabella d’Este, and I began creating my versions.

DSS: Would you consider those drawings or paintings?

JA: Yes, drawing and painting.

Years later, one of those Isabellas was sold in a Paris gallery. A wealthy New York couple bought it. Then they divorced, and the wife kept the artwork. She put it on consignment in a frame shop, and an American friend of ours, who had been a student at Penland School of Craft in North Carolina in the 60s, later saw it there and bought it.

Olga and I had spent a summer teaching at that school. She was initially invited to teach textiles, and after they learned about my work, they extended an invitation for me to teach drawing.

The town I grew up in was simple, and no one ever discussed art. I used to go to the movies with my brother three films a week, and that was the most exciting thing we did.

DSS: Can you tell me a bit about your relationship with your brother?

JA: He became a very successful lawyer.

I left California when I was very young; he stayed. I would only see him sometimes during vacations. He died a few years ago. He was a successful businessman. We were very different, completely different, really. I never fit in anywhere. I never felt “normal.” I was always solitary, and I did not have the same expectations most people have in life. He did, and he achieved what he set out to do.

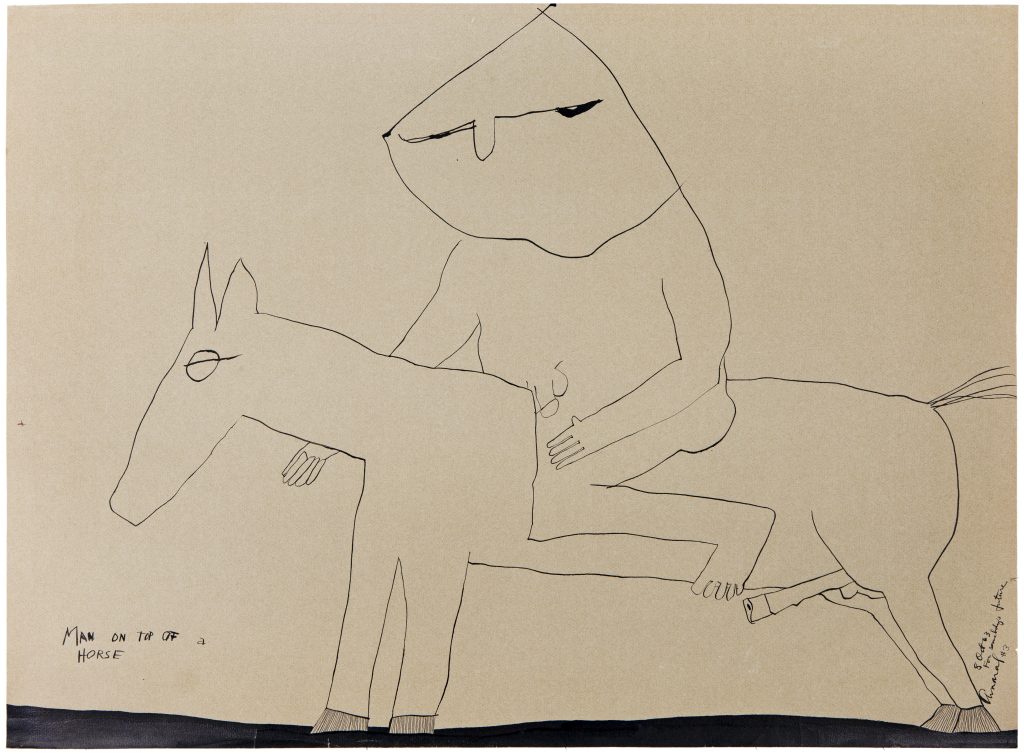

Man on Top of a Horse (Hombre encima de un caballo), 1963. 55 × 75 cm. Pencil and ink on paper. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

DSS: And your trip to Europe?

JA: In the late 1960s, Rogelio Salmona designed and built a house for us. A friend living in Barcelona suggested a home exchange, and we were intrigued. We had only just moved in, but we accepted the offer. We had never been to Europe.

Later, while visiting Paris in 1971, Olga’s brother-in-law, Paul Coulaud, offered to share his apartment with us for six months. That was our first extended stay in the city. While we were there, I was introduced to Albert Loeb, a traditional and well-established gallerist. His father had discovered and represented some of the great artists of early 20th-century Paris. Albert offered me a solo show for October, but it was actually February when I started working intensely, and everything came together. The show was a success, and he became a close friend. Thanks to him, my work reached Milan, Venice, and other cities. Those were creative and stimulating years for Olga and me, working in Paris.

Olga was weaving most of the time, developing her work and inventing her languages. Our two children accompanied us as well. (Salmona’s house was built in 1970. Jim tells me they were personal friends.)

(Although they had not been to Europe before, Jim’s friends and paternal family were from there. His father was born in the Azores, located off the coast of Portugal, but far out in the Atlantic Ocean. At nine years old, he moved to Massachusetts to milk cows, as Jim had already told me. Later, as an adult, his father found a job in Lisbon at the famous Café Brasileiro, where he worked as a waiter, the same café frequented by the poet Fernando Pessoa. This detail becomes strangely meaningful in light of Jim’s initial comment about his own “schizophrenia.” In Pessoa’s case, we might call it genius, the fully developed voices of his heteronymic poets. When Jim’s father returned to the U.S., he bought a car and drove from Massachusetts to California in the 1920s! Jim adds, amazed. There, he had a Portuguese cousin and decided to stay for good. That is where he met Jim’s mother, who was still in high school, working during lunch at her father’s restaurant, John Ratis, which was also the establishment’s name. She worked there during her break, Jim adds, visibly moved. Moreover eventually, that is where she met my father, and they got married. My father never wanted to return to Europe or Portugal after that).

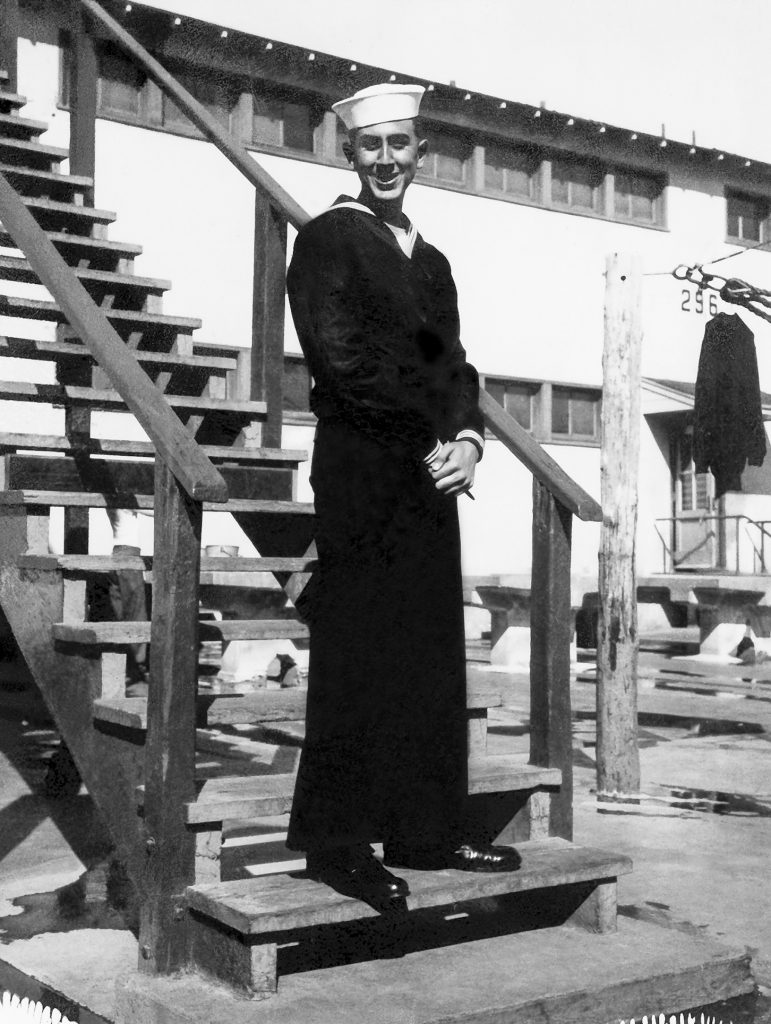

JA: At Stanford, I was a bad student, but I managed to graduate as an artist. I applied to the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where I met Olga. On the first day, I was signing up, and she walked in. Her English was not great, so I helped her with that and everything else during her time there. We became very close friends.That year, she returned to Bogotá, and I went back to San Francisco. There, I was called up for military service and sent to the U.S. Navy.

They had no idea what to do with an art student, so they sent me to the jungle in the Philippines, where I became the library director. But this was a military construction battalion, and the builders were not particularly interested in literature… So I spent two very lonely years there. More alone than one could be, as a poet-artist in the jungle, with no clear sense of what I wanted to do with my life.

Jim Amaral in Hong Kong, heading to the Philippines, 1956. Photo courtesy of the artist

When I returned, I was in crisis and decided to visit Olga, who had always deeply impressed me. She had started a small textile business. When I arrived in Colombia, I found her stunning. She used to be a little chubby, but now she was slim and elegant. We were struck immediately. (Though do not put that in, Daniel.) Soon, my visa expired, and that is when we got married. We were young artists and did not have a penny. After six months, we successfully rented a space on 81st Street and Ninth Avenue. We each had a workshop; mine was the dining room, and hers was a bedroom. It was a beautiful love story. We were 24. Soon after, our two children were born.

JA: Bogotá was not very welcoming. I was a gringo in 1957. People did not really know how to treat foreigners. The only ones around were businessmen, very far removed from the local society, which was, for its part, cold, closed off, and very particular about class and manners. I did not fit in not only because I did not speak Spanish, but also because I had habits and behaviors from elsewhere. I had just come out of two years of military service in a jungle; before that, I had studied at cutting-edge art schools, and before that, I was a kid from a remote town. But little by little, I found my footing in Colombia. I got a job, first at a furniture factory designing. The boss, a Swiss man, resigned, and I asked for the position. They told me I did not have the experience, and out of pride, I quit. So, Olga and I started our own furniture business. She designed and oversaw the textile production, and I designed many pieces and other things. I was still drawing here and there, but I did not know what or why. I did not consider myself a good draftsman. At Stanford, I had been chaotic, but this time, I trained, I made a commitment to learn professionally, and I did.

All of it was hard: the uprooting, the identity questions. Being in Colombia at that time meant being very far from any global cultural or information center. I went through severe depression. Now I understand it was the anxiety of not knowing how we were going to survive as artists. I underwent four years of psychoanalysis, and later, I returned to it during other periods in my life. It helped me a lot to channel my fears. I have recommended working with the unconscious to many people since then, and it is something I have explored in depth in my work.

(You could place Jim not just geographically but thematically, within the post-surrealist generation, a movement that officially began in California in 1934, which, like its predecessors, delved into the unconscious but sought to objectify it, to find a more direct connection between perception and meaning.)

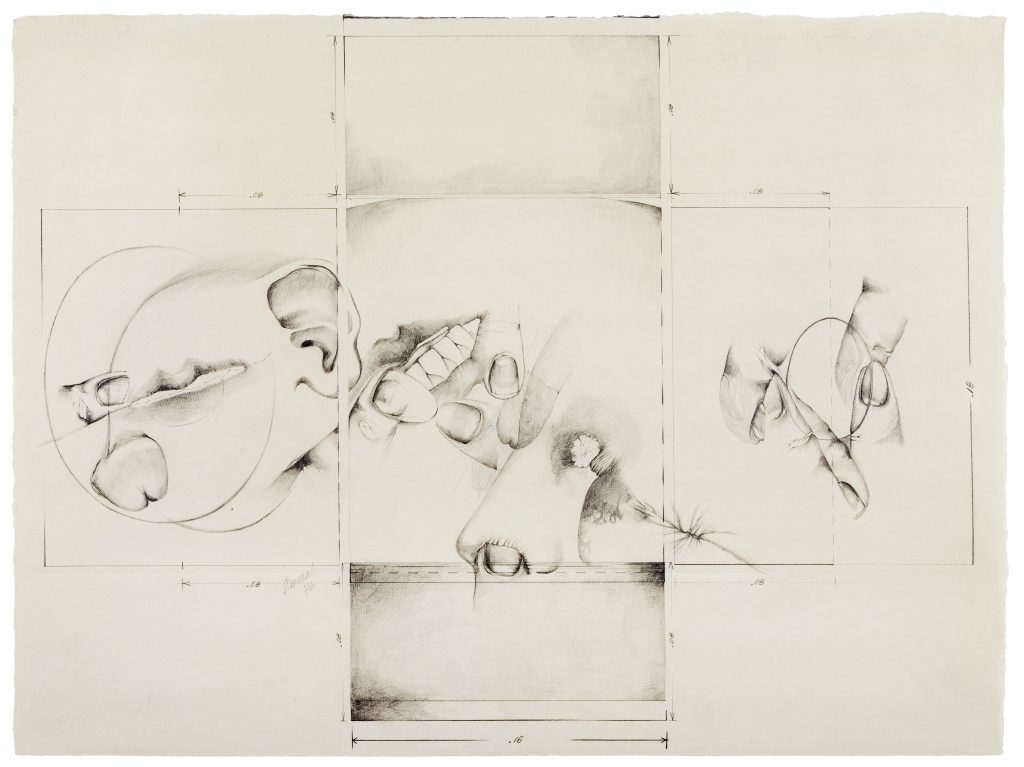

Jim Amaral. Left: Suite of Three Studies for a Box: Inside, Outside, and On Top (Suite de tres estudios para una caja: dentro, fuera y encima), No. 2, 36 × 54 cm. Pencil and ink on paper. 1976. Right: Untitled (Sin título), 29 × 39 cm. Pencil on paper. 1971. Photographs courtesy of the artist.

DSS: What a powerful story! It says so much about you and your work. Thank you for sharing it. I know this is not easy for you, as you have told me you prefer your work to speak for itself rather than being personally analyzed.

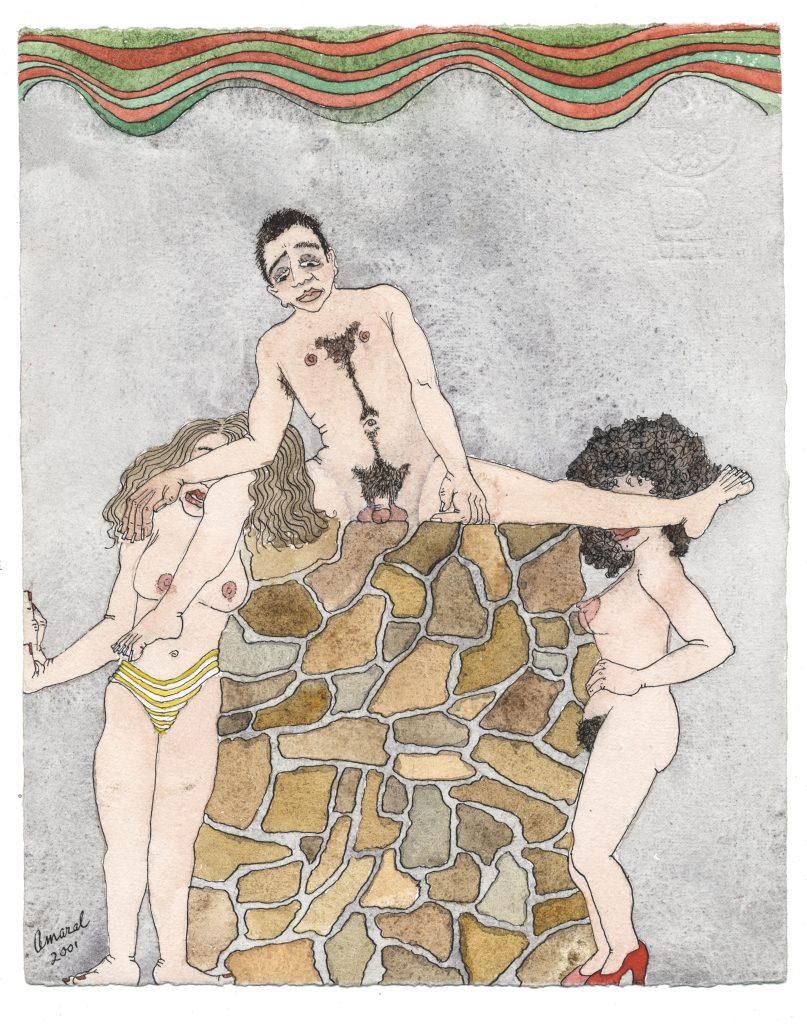

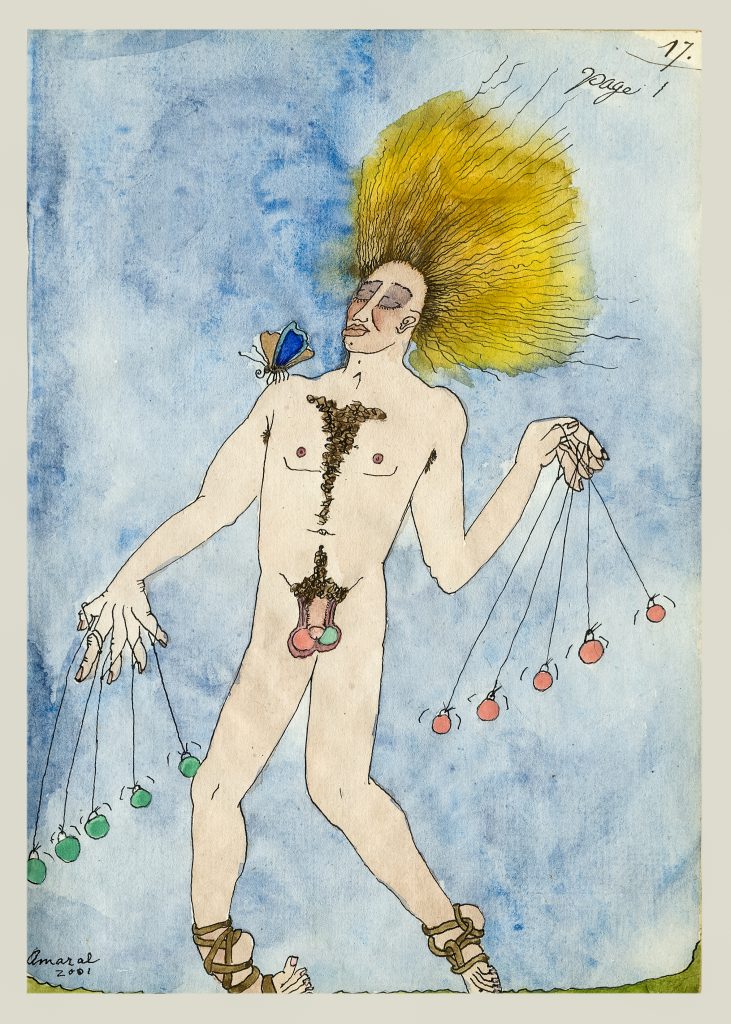

But these insights help us understand the depth and richness of your ideas, which is why I have pressed a bit. Let us change focus. I came up with some challenging and existential questions. You will know if and how you want to respond. For example, taboos, what do you think of death? Or of sexual and gender identity? Or of sex as a concept, which is very present in your drawings, more so than in your sculpture?

JA: Death, well, we are 92 now, so we think about it a lot (he laughs, one of his clever jokes).

When someone dies, they dissolve. I have seen someone die, and it is a moment when silence falls, and suddenly, there is no one there anymore. I do not believe in the afterlife, not in the heavens or hell. That whole idea feels like a form of oppression. You only truly understand death when you witness it.

(He asks if I have seen anyone die. I pause, then shake my head no. And you? Who did you see? Is it okay to ask?)

JA: My father, my mother, and Olga’s mother, for instance. When you go through that, you really see something about death. Sex. People often ask me about it. I always say that everyone, absolutely everyone, has genitals. Why is there a problem with something so normal? There are so many issues around sexuality (he makes a face as if to say so, so many), I chose to show how natural it is.

And in a beautiful way.

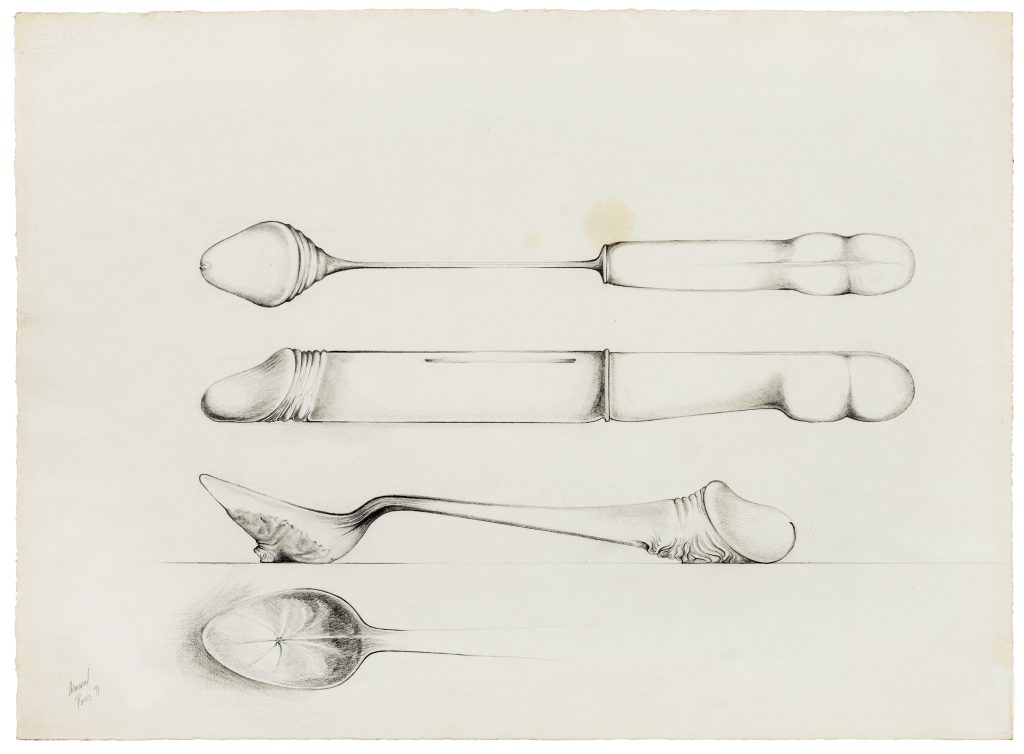

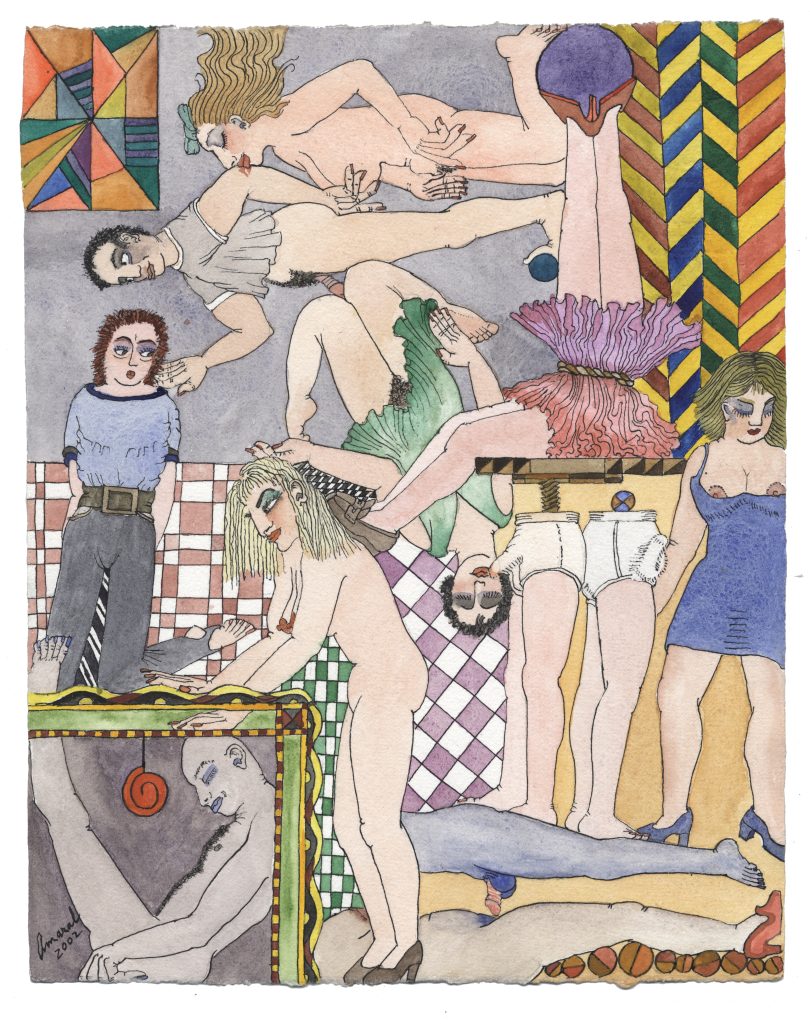

Per-se No. 008 (Per-se N.008), 2001. 31 × 25 cm. Watercolor and ink on paper. Photograph courtesy of the artist. Objects of Curiosity, Eighteen Illusions and Their Deceptive Titles (Objetos de curiosidad, dieciocho ilusiones y sus títulos engañosos), 2001. 35 × 28.5 × 2.5 cm. Mixed media. Photograph courtesy of the artist. Objects of Curiosity, Eighteen Illusions and Their Deceptive Titles (Objetos de curiosidad, dieciocho ilusiones y sus títulos engañosos), 2001. 35 × 28.5 × 2.5 cm. Mixed media. Per-se No. 040 (Per-se N.040), 2002. 31 × 25 cm. Watercolor and ink on paper. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

(This last sentence offered after a long silence strikes me as a brilliant, honest, and deeply moving statement about beauty and the beauty of genitals, which is something almost no one dares to say, at least not publicly!)

(We must remember: he was making this work in the prudish Bogotá of the pre-narco era. Here, I must add a personal memory: As a child, watching the news at my grandmother’s house in Manizales, Pablo Escobar was still alive. The news was about raids on his apartments in Medellín. In one of them, the camera zoomed in on a group of life-sized, erect glass phalluses intended as “art.” The journalist explained what they were imported, possibly from Italy. They were shown as a symbol of eccentricity. That image is still etched in my mind).

JA: They ask why I do not use colors in my patinas, and I say: Because I am not making something decorative.

(We discussed for a while how society, perhaps even more so today, still insists that art is merely decoration as if that were its sole function. However, as we know, and as the art world has repeated to exhaustion: Art is thought. It is aesthetic, philosophical, and subjective. It is not necessarily an object, as so many still believe. No one is opposed to the idea that art can decorate, and it is indeed one of its means of survival for institutions and artists alike. However, we also know that art has hybridized with every domain of human and social life. This is especially true in contexts where it is valued and understood. Still, it is something we must protect because this awareness could very well disappear, despite the monumental achievements of Western art in the last ten decades (or since Velázquez, to be more precise), which precisely began to challenge the artwork as a fetish or a trophy and to evolve toward experiences of other natures, ephemeral, conceptual, temporal).

JA: That is why my sculptures are meant to be touched and handled. That is why they move and make sounds. I want them to be living objects, to nourish the notion of art as an experience that transforms and affects. I do not know why I do what I do or why I did it.

Face (Cara) N.3, 1991. 38x23x20 cm. Bronze, 2001. Photo courtesy of the artist

DSS: What would you say to your audience about your work?

JA: I hope my work stimulates their minds.

My work is me. Everything I do is me. I love it all, and I hope people enjoy it as well.

DSS: Would you say you love your work?

JA: Yes.

Jim Amaral. Self-portrait (Autorretrato) 44×30 cm. Pencil and ink on paper. 1954. Photo courtesy of the artist

Thanks to:

Oficina Numena, Bogotá.

Instituto de Visión

Diego Amaral Ceballos

Valentina Amaral

Alexandra Vergara

Margaret Szyk