By Yohanna M Roa

Orlan and Yohanna M Roa. NYC May 2025, Focus Art Fair. Photo Juan Puntes

I spoke with ORLAN in May 2025, during her visit to New York – Focus Art Fair. I chose to focus our conversation on the question of representation, not only because it is a central theme in her work, which has been extensively documented and analyzed over the decades, but also because ORLAN has been a pioneer in her radical approach to the complex entanglements between the body, technology, and image. Equally pioneering is her deeply intersectional take on issues of representation.

In a society obsessed with the construction of racial, gendered, and social categories, designed to classify and control bodies, ORLAN has consistently pushed back. She has put her body on the front line, using it as a site of resistance, revelation, and confrontation. Through her corporeality, she has exposed the power structures that underpin the construction of the “other”, that other who, historically, is not the white man.

What struck me most during our conversation was realizing that ORLAN has never lost her critical edge or intellectual curiosity. She continues to probe those places where society hardens its grip on the body, imposes norms, and seeks to manipulate or silence it. Perhaps it is precisely this stance, radical, lucid, uncontainable, that makes her so difficult to classify within the frames imposed by heteronormative and patriarchal culture. ORLAN defies fixed categories because she has long understood, deconstructed, and disrupted the systems that seek to define and confine her.

Tue, 05/27 11:44 AM, New York City

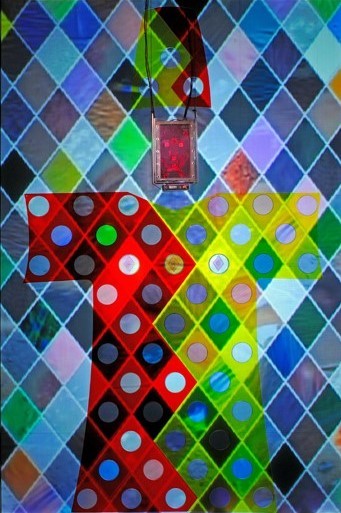

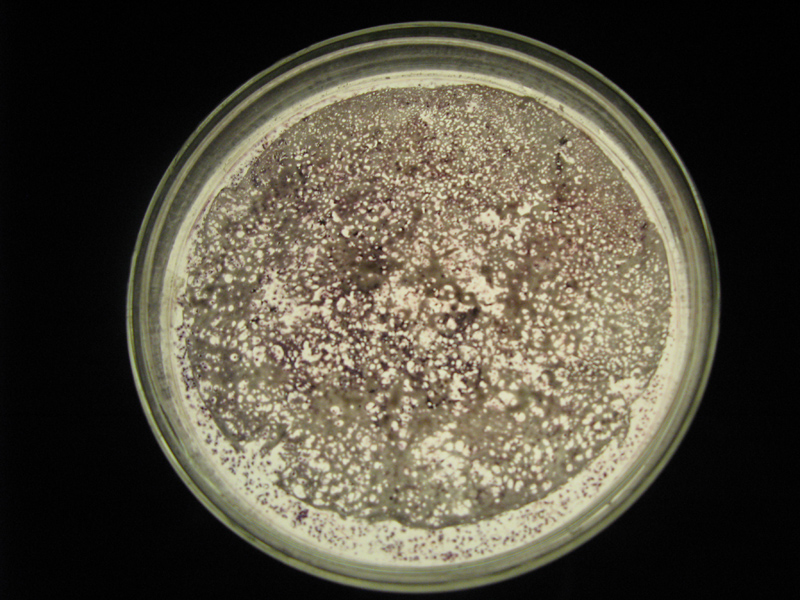

Exhibition view: HARLEQUIN’S COAT, part of sk-interfaces. 2008, a multimedia bioart installation created in collaboration with the Australian art and science collective Symbiotic A, curated by Jens Hauser, FACT, Liverpool, United Kingdom. © ORLAN

Yohanna:

Before we began the interview, you mentioned that it is politically important for you to introduce yourself and to make a political statement about your work.

Orlan:

I am ORLAN, among other things, and to the extent possible. My name is written in capital letters because I refuse to fall in line, I refuse to be confined to a straight path. I am an artist who is not bound to any specific artistic practice or a single medium. For me, working exclusively with one material or one artistic discipline is completely outdated. I claim the right to speak meaningfully about the world I live in, and in order to do that, I study social phenomena. Once I have studied a particular issue deeply enough to take a clear position, then I consider that position to be the spine of my work. It becomes the conceptual foundation of the piece. Once firmly grounded in that conceptual position, I ask myself: What materiality, what “flesh,” will I wrap around this spine? When I create a work of art, I think of it as creating a body. For me, the flesh comes after the concept. In this way, I allow myself to use an extensive range of media.

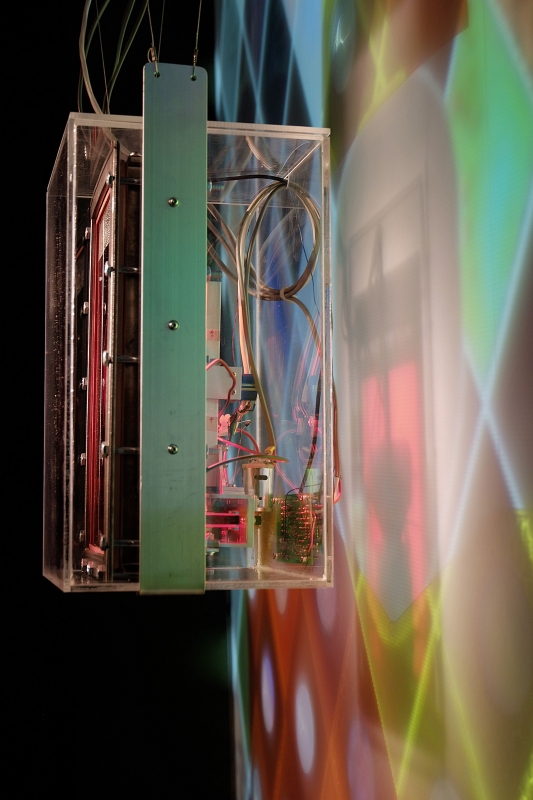

My work spans from robotics; I am currently doing a lot with artificial intelligence—to sculptures in Carrara marble, resin, and 3D-printed forms, among many others. I have also worked with photography, as you can see here in this exhibition, and with video works. But I’ve also cultivated my own cells. I have worked with bio-art, even cultivating my own intestinal, vaginal, and oral flora. For me, it’s absolutely essential to define each work’s materiality in a way that allows it to reveal the essence of the idea and concept behind it.

Suture. 7th surgery performance, 1993 © ORLAN

Yohanna:

Throughout your career, the relationship with representation, the production and mediation of the image, has been central, perhaps the defining theme of your artistic practice. For this interview, I would like to focus on that theme, mainly because it allows you to speak from an intersectional feminist perspective, addressing the intersections of race, gender, and embodiment in your work. The 2007 piece Suture, where questions of bodily fragmentation and reconfiguration come to the fore. Could you reflect on how this work challenges issues related to race and gender?

Orlan:

That is a fundamental question because my work challenges conventional narratives around bodily integrity and identity. My entire practice can be seen as one continuous inquiry, a questioning of the body’s status in society under various cultural or traditional pressures. And tradition, frankly, has been used to justify many, many absurdities, often without ever being critically examined.

My work also responds to the pressures exerted not only by culture but also by the religions we practice and by politics. The body is under immense pressure depending on the political regime or ideological framework.

I am in Palmo, in France. We have a government, we have politics, and we are grappling with the power structures rooted in the family unit. We are in the midst of a significant conflict. We live here today surrounded by people who really have not listened to us, and I am thrilled to be here with you in New York. While we may not physically be here, we are present in the Constitution. We are among the first to be here this way, and I hope we can chart a path forward together. It is essential to me that this moment marks the beginning of the family—being seen, being acknowledged—for the first time.

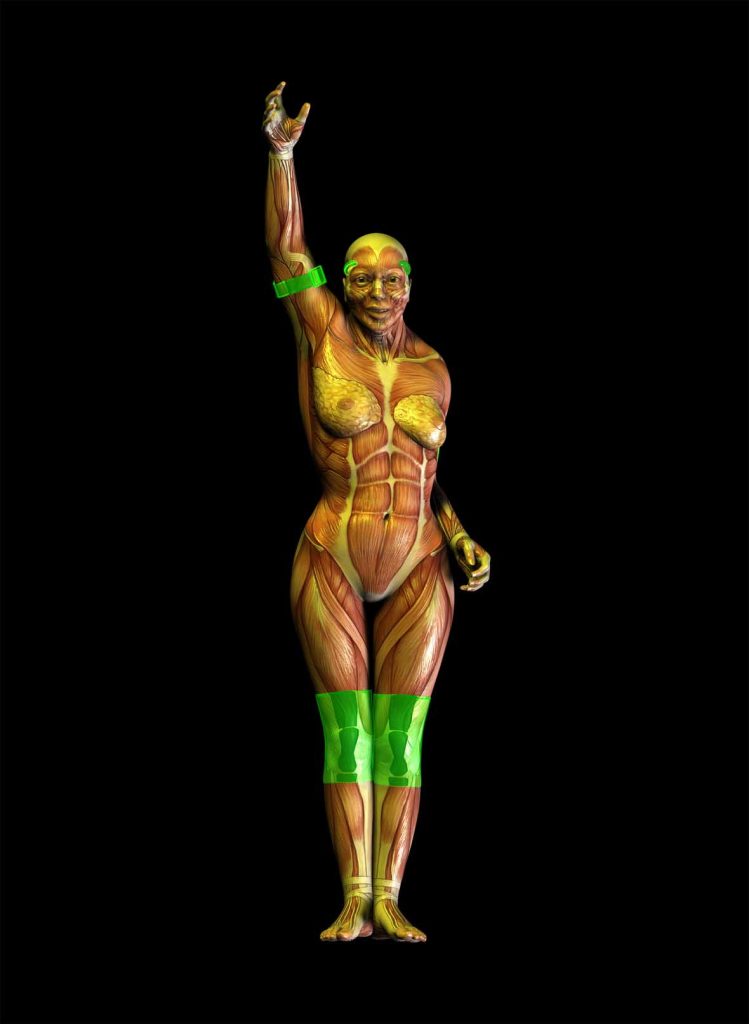

ORLAN, Flayed liberty and Two ORLAN’s bodies, 2013. Single Chanel video, color, silent, 28:32 minutes. © ORLAN

Yohanna:

Discuss Freedom in Flayed Body and Two ORLAN Bodies (2013).

In these works, you set out to merge two historical periods: the anatomical diagrams of Andreas Vesalius and your contemporary interventions, offering a cyborg reading of the body. In particular, these pieces reverse your usual process. Whereas you often use the external representation of the body to reveal social frameworks of control, here you remove the skin from your own body, preserving only two prosthetics: your face and kneepads. Could you speak about your feminist position in approaching this anatomical representation? What does it mean to expose the “interior” of the body from a feminist perspective?

Orlan:

This video work is a perfect illustration. For me, it is a kind of manifesto, as I often say from Palais Anglais. Because, depending on who holds power depending on politics the body, and especially the female body, is entirely instrumentalized. We are seeing it clearly now with abortion being banned in some places. I am very proud that in France, not only is abortion legal but it is now enshrined in the Constitution. We are the first country to do so, and I take great pride in that. I hope other countries begin to realize how vitally important it is that women have the freedom to decide whether or not they want to have children.

This work encapsulates what I do at the feminist level. Honestly, I wish I did not have to be a feminist. I wish all of these issues were already resolved, that feminism did not have to be one more concern to carry. However, the reality is otherwise. For this piece, I created a self-portrait without skin. It was essential to me that the image be skinless because most artists are, metaphorically, “flayed.” Moreover, I had to flay myself to make this work.

Being flayed holds deep social meaning because, without skin, racism becomes impossible. You cannot see if someone is white, yellow, or Black. That is why it was crucial for me to make a flayed self-portrait. The piece is called Freedom Flayed. And, as you rightly pointed out, I brought together two elements: Vesalius’s anatomical plates and a reading from cyberculture.

Also, from a feminist standpoint, I like to represent myself with a strong, mature, and thick body not the type of body typically seen on fashion runways, which are emaciated and almost skeletal. Our era hates flesh. Models are essentially hangers without meat. Most of them have anorexia or are women who are forbidden from eating in order to maintain that body type. I wanted to show this fusion between older cyberculture, with prosthetics that appear almost caustic, and the anatomical plates of Vesalius. These represent two entirely different ways of reading the body.

Another key element is that I chose to depict myself in the pose of the Statue of Liberty. Because today, many of our freedoms are being taken away. For instance, for a woman to show her nude body or even just one breast remains a problem in our society, and is entirely absurd. Men can walk down the street shirtless. I saw a few just the other day, and no one batted an eye. However, if a woman did the same, people would scream for help.

On the internet, breasts are censored. If I post a photo of my work that includes breasts, I will be banned from the platform immediately, or my blog will shut down. It is absurd, especially when these objections often come from religious individuals who believe in a God and who say that God created humans in His image. So why is it forbidden to show the body, which would be God’s masterpiece? On the contrary, we should be showing it. Displaying sexuality is a way of honoring God’s creation, not mine, but God’s, for those who believe. And the body itself, in all its complexity. We live in a time that resembles Michelangelo’s era or thereafter when they painted trousers onto masterpieces. In the Sistine Chapel, they painted pants over the figures. Can you explain that? Why were they covered?

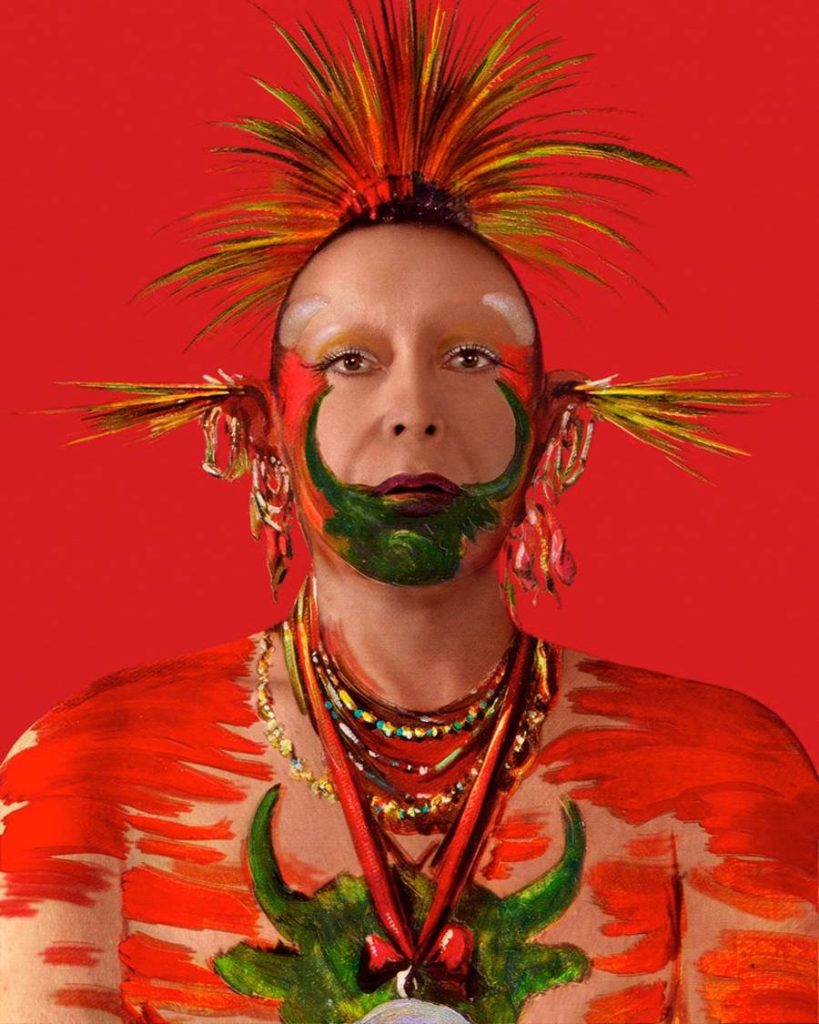

Left to right: Le Drapé, Le Barroco, Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 1979 and other sculptures by plis. / American Indian Self-Hybridization #11: Painting Portrait of La-doo-ke-an, Buffalo Bull, a Great Pawnee Warrior, with ORLAN’s Photographic Portrait, 2006, digital photography / Refiguration, Self-Hybridization Pre-Columbian no.18, 1998. Cibachrome print. Photograph. © ORLAN

Yohanna:

In your Self-Hybridization series, one of the most extensive bodies of work in your career you continually explore themes such as the body, the sacred, femininity, beauty, and hybridization. Initially, your focus was primarily on European imagery. However, in 1998, you began to work with non-Western representations, including African cultures, Native American iconography, and Mayan aesthetics. You even traveled to Mexico and visited Mérida in Yucatán. What led you to explore this historical and cultural lineage? Moreover, how did these encounters influence or challenge your understanding of identity and the body?

Orlan:

I am an advocate for nomadic, multiple, and ever-changing identities. To me, fixed identities inevitably lead to violence, to horrors, to the construction of communities that end up fighting one another. I have traveled extensively throughout my life, but you can broadly divide my work into three main phases. The first phase was focused on my own culture, Western Christian culture. That period involved a critical interrogation of Christian identity, always approached with a necessary critical distance. The second phase, marked by my surgical performance operations, was a hinge between the first and third periods.

The third phase encompasses an entire body of work to transcend my Eurocentrism. To move beyond this narrow perspective, I traveled widely and began expressing my deep admiration for the diverse cultures I encountered. I spent significant time in Latin America and worked with Indigenous peoples from the Americas, as you can see in that space portrayed in these photographs behind me, as well as with African cultures.

This entire series is in black and white because it is based on ethnographic photography, the earliest photographic representation of the so-called “Other.” The result is a collection of staged images in which I blend my face with African sculptures or masks that I deeply admire. This hybridization is, in essence, an act of admiration, an invitation to closeness. I propose that just as I feel close to the Other, the Other may also feel close to me. In that way, a real, respectful encounter can occur, one that extends a hand across the frozen wall erected between us. That said, I always maintain a degree of critical distance. For example, in the Native American works, I depict myself dressed as a tribal chief; this is a deliberate critique because Native cultures would never have accepted a woman as chief. That contradiction is intentional.

ORLANoide, a work in progress, was shown in 2018 as part of the Artistes et Robots exhibition at the Grand Palais, curated by Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Jérôme Neutres. It’s a humanoid robot with ORLAN’s face, endowed with AI and collective and social intelligence.© ORLAN

Yohanna:

Your work frequently involves technological interventions on or around the body. How do you see the role of technology in shaping new forms of identity, particularly for women and marginalized bodies?

Orlan:

I work extensively with new technologies because artificial intelligence is, without a doubt, one of the defining social phenomena of our time, it is taking over. I view AI as a positive development because, frankly, we, as human beings, are becoming obsolete. We do not have nearly enough memory or cognitive capacity to face the complexity of our current reality.

In 2025, just to be aware of what has shaped me, who I am, and what I can do, I have to ask: how many books of history, philosophy, art, science, and biotechnology can AI not only read but also integrate and retain? That level of memory and processing is impossible for humans. We are already seeing this in medicine. Diagnoses are increasingly done with the help of AI because doctors can no longer manage the volume of data; they cannot process it all. So yes, I believe in new technologies. In fact, I am searching for a new wave of technologies that is just, responsible, and capable of rebuilding what the first wave has dismantled, broken, or destroyed.

This wave is already emerging. For instance, small jellyfish-like robots have been deployed in the oceans to clean up the disgusting particles we’ve dumped into the sea.

I actively participate in this movement. I believe it’s imperative, especially today as a woman, to adopt this position, not to fear new technologies but to evaluate the chain reactions they trigger thoughtfully and to be profoundly careful not to destroy living ecosystems but to respect them. My most recent series addresses my concern for endangered species. I depict these animals using robots made from recycled plastic and recyclable materials. For me, working with recycled objects and materials is essential. These robots resemble me and are “in love” with the animals; they are trying to prevent their extinction. We have to love these beings if we hope to ensure they do not disappear.

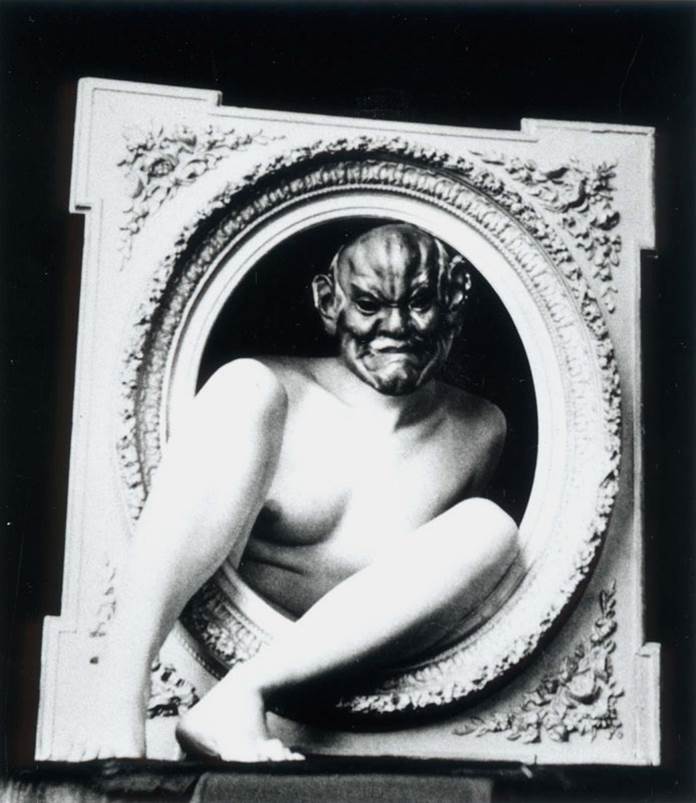

Attempting to break out of the frame with a mask, (Tentative de sortir du cadre avec masque)1965, black and white vintage photograph, unique print. © ORLAN

Yohanna:

Why and when did you become a feminist, and how did that decision shape your work? What has been significant for you in adopting a feminist perspective in your artistic practice?

ORLAN And Yohanna M Roa. NYC Mayo 2025. Photo Juan Puntes

ORLAN:

From a feminist perspective, one of my most important works—and you can see a photo of it here—is the surgical performance operations I did in New York (Orlan points to some of the works we are looking at). What was crucial to me was that I became interested in cosmetic surgery because it’s undeniably a phenomenon of our time. I wanted to interrogate it by using it and destabilizing it.

I had implants inserted where they are usually placed in the cheekbones, but also on either side of my forehead. I wanted to show that what is considered ugly or monstrous depends entirely on the historical and geographical context, where you are supposed to style your hair a certain way, dress a certain way, and so on.

For instance, in this series, a woman from the highlands with a large, stretched lip is incredibly proud of her seductive power. In her geographic location, within her tribe, a large lip was considered highly attractive to men. So, this woman is genuinely pleased because she has strong seductive power over men. However, if you or I had a lip like that, we would immediately be seen as undesirable completely outside the norm. What I wanted to demonstrate is that beauty is simply a matter of the ideological norms of a given place and time. With these surgical performances, when I placed these implants, people reacted very aggressively, violently, even. They said the same things that were once told about the Impressionists, that their work was horrific, that it was so ugly a pregnant woman might go into labor from seeing it. They said they did not know how to paint and that it was the most significant fraud in art history. However, today, Impressionist paintings sell for astronomical prices and are even printed on Christmas chocolate boxes.

That is precisely what happened to me; they said I was insane, that it was not art, that it was disgusting. But now, in recent years, people often say to me, “Oh, you are beautiful,” or “Have you seen my two bumps?” and they will add, “Oh yes, they suit you.” This perfectly demonstrates that our customs and traditions are historically contingent, entirely dependent on where we are, when, what we do, and our place in the world.

Yohanna:

Artistically speaking, what political aspirations or expectations do you hold for the future about the body, especially your own body? How do you envision the body as a site of resistance or transformation in the coming years?

Orlan:

I truly believe the body is political, everything we do is political, and the personal is political. That is deeply important to me. I consider myself a body—entirely a body—nothing but a body. It is my body that thinks. I deeply believe that the body is a site of resistance and transformation. What I hope for is less and less pressure on bodies and more and more freedom for people to be trans if they want to, to be bisexual if they want to, to move from male to female, to have different identities throughout their lives.

For me, it is crucial that our bodies belong to us. It’s the only body we have for our entire lives, and we should be able to do with it what we want, how we want, without absurd regulations that confine us, box us in, or trap us within systems we can no longer escape from. I hope and I truly believe that art will change the world and tip the scales to the other side. Right now, we are living through a resurgence of religion, racism, and all the horrors we have tried to contain: stereotypes, restrictions, a lack of freedom, a lack of sensitivity, societal violence, war…

On the other side of the scale, art and artists will build a brighter world that is more open, sensitive, and welcoming of transformation and all the joys in art and life. Through art, we can counterbalance the rise of the far right, fascism, and totalitarianism. I always remember what the great philosopher Nietzsche said: “We have art in order not to die of the truth.” Truth matters deeply to me, but truth can only be proven and accepted as such. Right now, in your country, people swear on the Bible and then say utterly contradictory things. For example, why did you wear red today? (Yohanna: Orlan is referring to my red lipstick.) You know I do not like red, I am allergic to red. She wore it on purpose. And you reply: “I am not wearing red; I am wearing white and blue.” Moreover, I say: “No, you are wearing red. I see it, I feel it.” That is my so-called truth, without evidence. And yet it is accepted as truth, not as falsehood. I want a truth based on evidence. Do you understand?

Yohanna:

The answer lies in a future rendezvous—most likely in Paris.

The endangered polar bear and new robots made from recycled objects and materials. Version 2. 2024. © ORLAN