Mia Westerlund Roosen at Nunu Fine Art and the Politics of Flesh, Matter, and VerticalityThe Naughty Rebellion

By Yohanna Magdalene Roa

Upon entering Nunu Fine Art to visit Mia Westerlund Roosen’s exhibition, the experience was that of moving through a constellation of sculptural-spatial works marked by a monumental tension between flesh and verticality, between the human and that which exceeds it. Westerlund’s practice articulates itself as an unruly rebellion: a hybrid practice encompassing sculpture, drawing, process, and a form of latent performance in which the body, even when not figuratively present, remains the measure of all things.

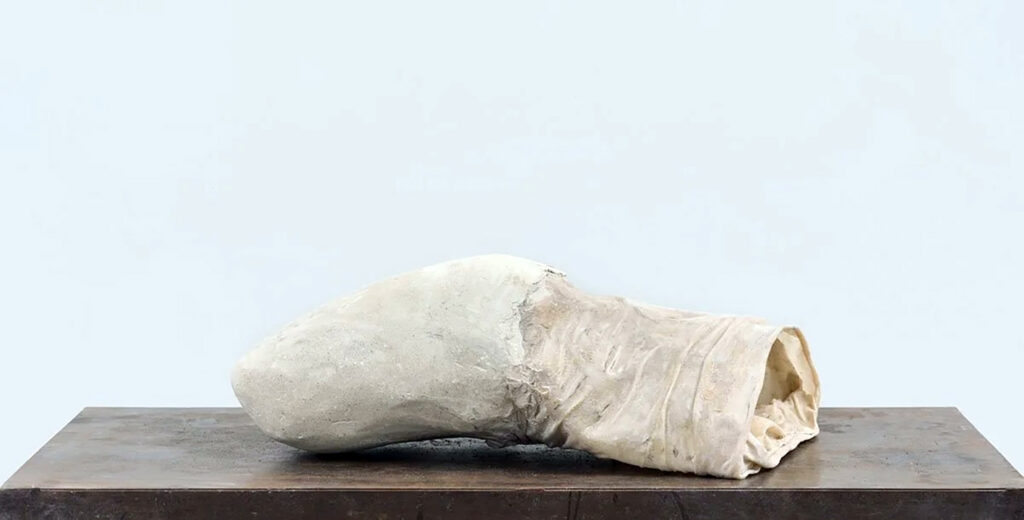

Mia Westerlund Roosen. Sac, 2019. Concrete, flannel, and resin. 11 1/2 x 20 x 15 1/2 in

From the entrance, a smaller-scale sculpture, yet one of great power ( Sac 2019), made of concrete, flannel, and resin, rests on a white shelf without truly resting upon it. It vibrates. It resembles a suspended fragment of flesh, latent, as if on the verge of being activated or of rising at any moment. It is not a closed form, but a body in waiting. Further along, a corridor unfolds like an epidermal passage: paintings and drawings of phallic forms, some conical, others oblique, accompany the viewer’s movement as a sequence of skins, organs, soft obelisks. At the far end, two monumental sculptures (Conical and Heat, 1981), in concrete and encaustic, rise semi-inclined and pointed, gesturing upward toward a space that no longer belongs to the human body.

Mia Westerlund Roosen. Heat, 1981. Concrete and encaustic. Dim, 154 x 36 x 62 in

Standing there, at the threshold, experiencing the works, a fragment of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s poem Sor Juana’s Dream / Primero sueño1 came to me almost as an epiphany, not as a literary reference, but as a conceptual architecture. In this poem, Sor Juana imagines the impulse of human understanding as a pyramidal form, born of the earth, rising ambitiously toward the sky: “Pyramidal and ominous, a shadow / born of the earth rose skyward / the lofty tip of vain obelisks, / seeking to scale the stars.” This is not an ornamental metaphor, but a radical reflection on the desire for totality, on the audacity of a mind that attempts to encompass the cosmos and inevitably confronts its own limit.

Westerlund Roosen’s sculptures seem to embody that same gesture: architectural bodies emerging from the terrestrial, from cement, wax, weight, and yet projecting themselves toward an unreachable sky. Concrete, a material the artist defines as “magical” due to its transformation from liquid to solid, becomes here a form of material thinking. Encaustic, applied manually layer upon layer, does not function as a pictorial surface but as skin: transparency, flesh, blood, veins, arteries. The artist first constructs the concrete components and later assembles them, adhering an organic tissue onto this rigid taxonomy, almost as if caressing the body of the sculpture, endowing it with a vulnerable epidermis.

Mia Westerlund Roosen. Untitled Drawing 2, 1979. Oil stick, pastel, and charcoal on paper. 13 x 7 in

Sor Juana reminds us that these obelisks, however high they rise, belong to the human rather than the divine. They are forms born of the earth. In the same way, Mia’s sculptures point skyward with contained violence, their tips seeming to tear through the ceiling and compel us to lift our gaze. There is in them an unmistakable ambition: the desire for absolute knowledge, for totality, for going beyond the body. “Seeking to scale the stars,” Sor Juana writes. But the poem is clear: the ascent fails. Understanding grows weary, fails to reach even the lunar orbit, and retreats.

That failure is not defeat, but recognition. It is precisely there that Westerlund Roosen’s work becomes profoundly human. Besides those tense, vertical forms, another phallic sculpture rests, more horizontal, closer to flesh and earth. It reclines like a body after excess, after daring and excitation. And if we turn our gaze back toward the entrance, Billow remains there, waiting, latent, as if the cycle might begin again. Ascent, fall, rest. Like a choreographic sequence.

Nothing in this experience is intimidating, because scale never imposes itself; it is always measured in relation to the viewer’s body. We become direct witnesses to an encounter that confronts us with our own finitude, with the awareness that flesh and materiality are the only possible vehicles through which we can attempt to grasp the infinite.

Born in New York in 1942, Mia Westerlund Roosen’s trajectory unfolds from the 1970s to the present as a vital continuum rather than a succession of closed stages. Her childhood was marked by a strong duality: a creative mother associated with chaos and a frustrated artistic vocation, and a father linked to order, containment, and an aversion to disorder. Becoming an artist was, for her, an act of symbolic restitution: “it was like avenging my mother.” Added to this is an early relationship with dance, initially conceived as a possible professional path, which allowed her to recognize, from an early age, the physical, temporal, and economic limits of the body.

Dance permeates her entire practice: in the body–space relationship, in notions of balance, weight, and tension, and in the understanding of sculpture as body rather than autonomous object. Her dialogue with Eva Hesse, along with her deep knowledge of minimalism, was always employed to be broken, reinforcing a process-based, intuitive, and not entirely rational logic. Westerlund Roosen works from the gut, from the emotional and the corporeal. Accident, torsion, and imperfection are not corrected; they are affirmed. The process is not concealed; the work must show how it was made.

Mia Westerlund Roosen. Conical, 1981. Concrete and encaustic. Dim, 46 x 36 x 60 in

Mia Westerlund Roosen. Heat 3, 1981. Charcoal and pastel on paper. Dim, 19 x 25 in

The use of accessible materials such as cement, wax, asphalt, steel, and lead is an ethical and structural decision rather than a limitation. Encaustic, in this context, is not paint; it is skin. Basic geometric forms, cones, rectangles, and circles appear with full awareness of their phallic charge, assumed frontally and provocatively. They are not illustrative symbols, but bodies: presence, mass, scale.

Humor runs through this practice as a critical and destabilizing force, a mischievous and radical form of resistance against formal neutrality and modernist standardization. Thinking and feeling are not opposing operations, but equivalent ones. In that equivalence, the artist’s work asserts itself as embodied thought that, as in Sor Juana’s dream / Primero sueño, dares to reach the limits of knowledge only to recognize itself, once again, as human, carnal, and finite.

At Nunu Fine Art, New York, Mia Westerlund Roosen’s works insist on that human gesture Sor Juana had already intuited: rising toward the infinite only to return, exhausted and lucid, to matter. In doing so, they do more than establish a dialogue with the city’s material history; they compel us to rethink finitude, flesh, and matter as epistemological matrices of art today.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Primero sueño

Fragmento, Original Version (1685)2

Piramidal, funesta, de la tierra

nacida sombra, al cielo encaminaba

de vanos obeliscos punta altiva,

escalar pretendiendo las estrellas;

si bien sus luces bellas

—exentas siempre, siempre rutilantes—

la tenebrosa guerra

que con negros vapores le intimaba

la vaporosa sombra fugitiva

burlaban tan distantes,

que su atezado ceño

al superior convexo aún no llegaba

del orbe de la luna;

pues ya en su altura misma fatigada,

cediendo al peso grave,

retrocedió cobarde.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, First Dream

Fragment, English. Transtated 19863

Pyramidal and ominous, a shadow

born of the earth rose skyward,

the lofty tip of vain obelisks

striving to scale the stars;

though their beautiful lights,

—ever exempt, ever resplendent—

mocked from such distance

the dark struggle

the vaporous, fleeting shadow

waged against them with blackened fumes,

so that its darkened brow

did not yet reach

the upper curve

of the lunar sphere;

for already, fatigued at its own height,

yielding to its heavy weight,

it retreated, undone.

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648/1651–1695) was a poet, philosopher, and Hieronymite nun from New Spain, and is regarded as one of the most significant figures of the Hispanic Baroque and an early radical voice of modern intellectual thought in the Americas. Primero sueño (First Dream), written around 1685 and published posthumously in 1692, is her most ambitious philosophical poem and the only one not composed for a specific commission. The poem articulates an allegory of human cognition: the mind, figured as a pyramidal shadow or obelisk, rises from the earth in an attempt to attain total knowledge, only to confront its limits and return to bodily, finite existence. Long read as a meditation on reason, corporeality, and the productive failure of absolute knowledge, Primero sueño is a foundational text for understanding the relationship between intellect, ambition, and materiality in Baroque thought.

Reference, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Primero sueño, ca. 1685; published in Segundo volumen de las obras de Soror Juana Inés de la Cruz, Seville, 1692. ↩︎ - Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Primero sueño, ca. 1685. En: Obras completas, edición de Alfonso Méndez Plancarte, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951. ↩︎

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Sor Juana’s dream. Translated, introduced, and commented by Luis Harss. New York, NY: Lumen Books, 1986. ↩︎