By Yohanna M. Roa

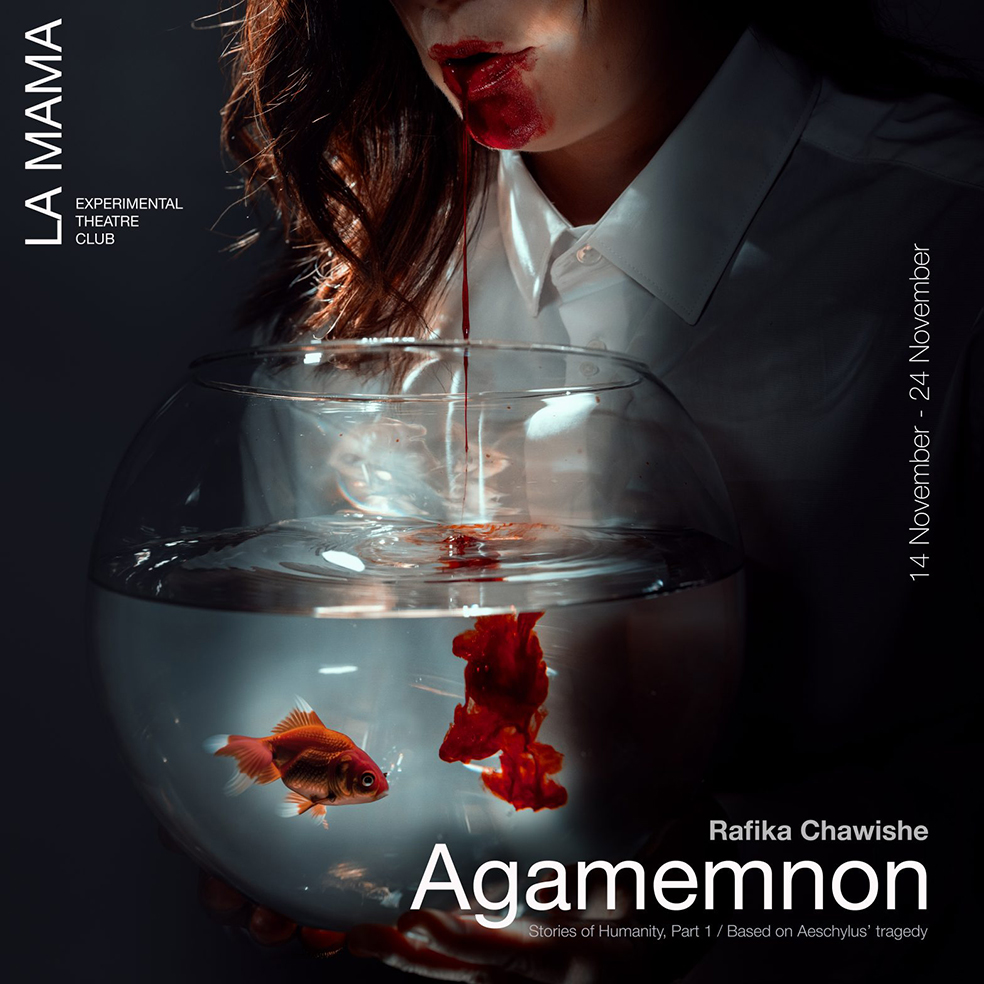

Concept, direction, and performance by Rafika Chawishe

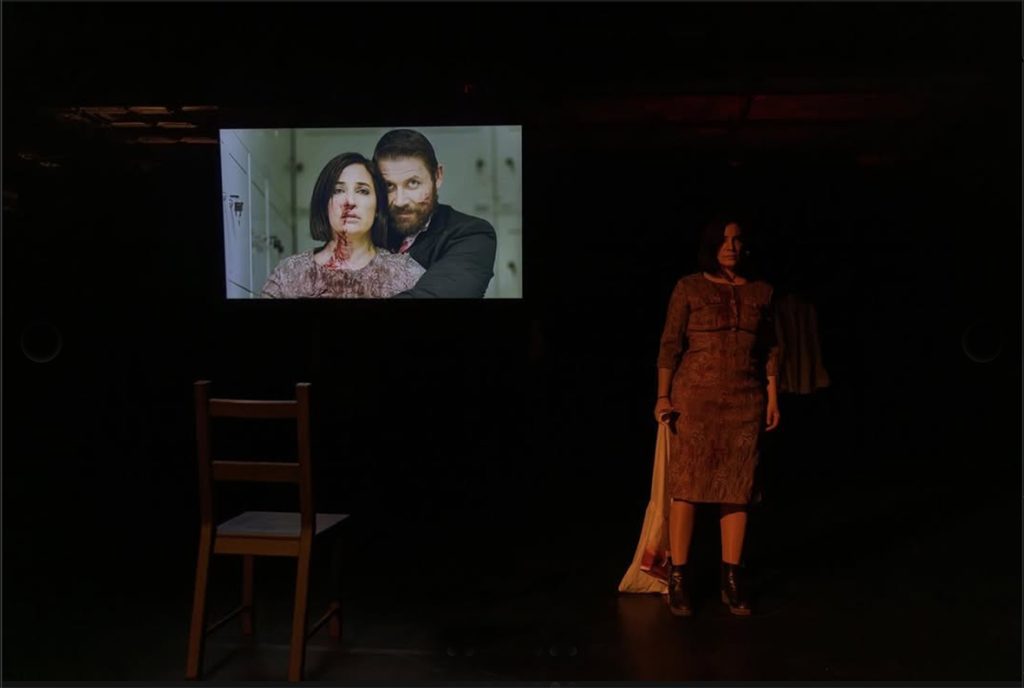

Rafika appears in the dim light of the stage, her bodily posture making us feel that she carries on her shoulders the weight of human violence: the intoxicating joy of the hero, the exacerbation of war, the cries of abused women, and the mourning of women who grieve their children. Eventually, she engages in dialogue or interacts with archival film material, interviews with refugee women, and recreations of scenes from the original piece by Aeschylus, which are projected behind her. Undoubtedly, the staging is flawless and the performance is powerful. In Agamemnon: The Circle of Blood, Chawishe successfully updates Aeschylus’s classic text, placing it in a contemporary social and political context through intelligent, relevant, and bold dramaturgy. With impressive histrionic skill, she sustains the character of Clytemnestra through various stories of refugee women, clearly conveying their individual pain. However, the true power and effectiveness of her performance lies in her ability to bear down on us the weight of history, allowing us to see, from a broad perspective, what we, as a society, have built and the need to take responsibility for what we will do in the future.

Foto. @lamamaetc Instagram

According to Jorge Luis Borges, “In an infinite period of time, all things happen to every person. […] Like Cornelius Agrippa, I am God, I am a hero, I am a philosopher, I am a demon, and I am the world, which is a tiring way of saying that I am not” (Borges, 1941)1 These words resonate deeply with the work of Rafika Chawishe, who, in her U.S. debut with Agamemnon: The Circle of Blood, presented at La MaMa,2 explores the cyclical nature of violence, power, and suffering that perpetuates endlessly throughout history. Paraphrasing Chawishe in a conversation we had in New York City, she stated: “war is a machine for producing power and money; there are no winners. There have never been any winners in any war—only victims: the dictator, the hero, the soldier, the women, the refugees—all are victims. War is a reproduction machine for victims.”

The script combines Aeschylus’s words with poems by Yannis Ritsos and original monologues by Chawishe. This textual collaboration enriches the work, adding existential depth to the characters. Through a potent monologue, the actress and director guides the audience through three simultaneous historical moments linked by a central theme: the structural violence of war that underpins human civilization. The play juxtaposes fragments of the original text with archival stories and video projections documenting the courage, pain, and resilience of migrant and refugee women. These visceral and direct narratives evoke a collective pain that has transformed into an “infinite present.” The play reminds us that humanity has yet to learn from its past, continuing to perpetuate cycles of war, death, rape, and destruction.

The use of archival materials documenting real stories of refugees and migrants replaces the traditional chorus of Aeschylus’s play. These testimonies, accompanied by projected images, serve as a critical tool to expose the contradictions of modern humanitarian systems. The archive bridges the past and present, demonstrating how individual tragedies evolve into a collective narrative transcending time. The work critiques the hypocrisy of international aid policies, which often fail to address the root causes of displacement and war. Cassandra, a prophet in the original play, is portrayed in Chawishe’s version as a tragic figure who embodies society’s marginalized. Her monologue is based on the actual testimony of a refugee, linking her personal tragedy to current crises of displacement and exploitation. If these refugees are the prophets—mediators between God and humanity—what divine message do they bring to society?

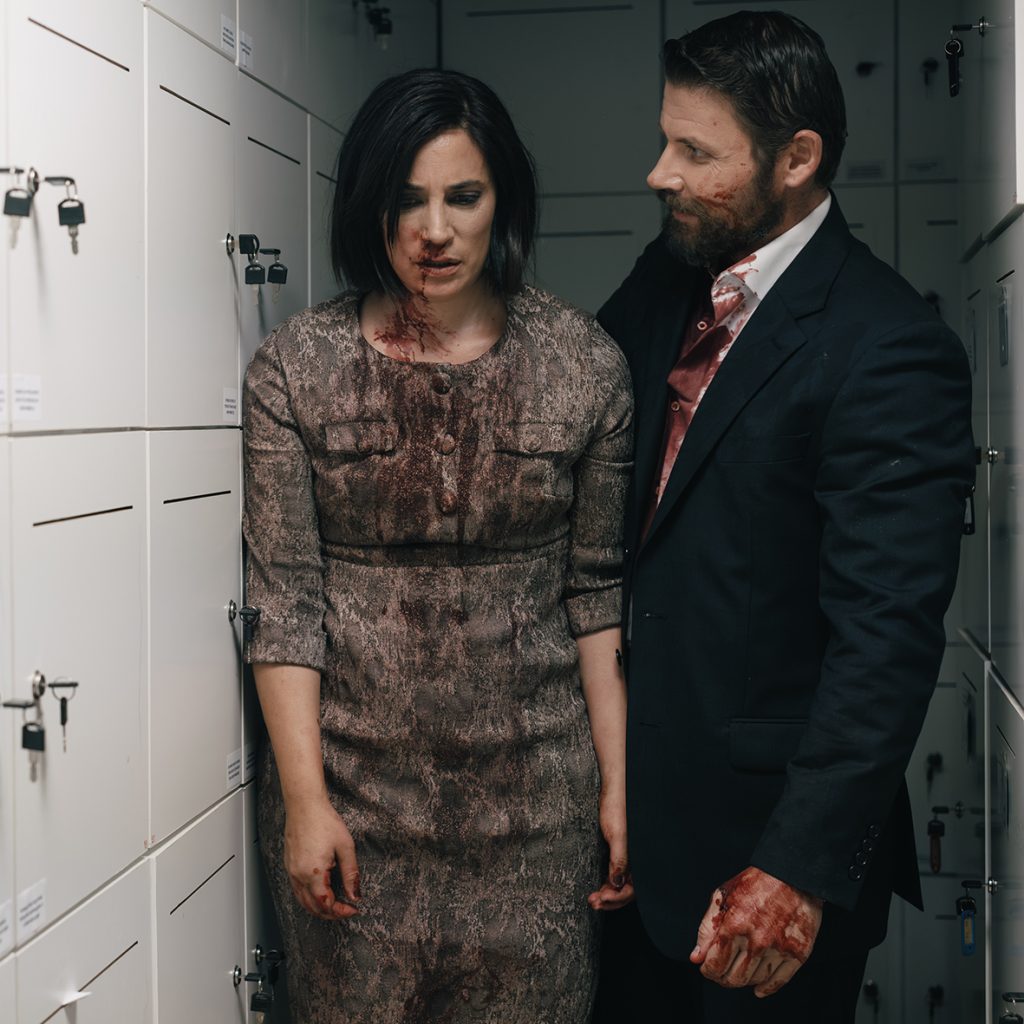

One of the most striking aspects of the adaptation is Chawishe’s portrayal of Clytemnestra. Traditionally seen as a vengeful figure, Clytemnestra becomes the symbol of millions of women fighting for justice and dignity. She embodies the mothers who tirelessly search for the bodies of their missing children, victims of war, sexual violence, or trafficking. She represents the women who have historically been asked to quietly search for their children, not destroy monuments, not break store windows, not cry in the streets, and not kill Agamemnon—even though doing so would stop him from continuing to kill their children. Rather than limiting her to her traditional role, Chawishe grants Clytemnestra agency, transforming her into a figure who denounces patriarchal structures and societal demands that silence her pain. Many of these women, like Clytemnestra, are reduced to silence while being expected to fulfill the roles society has imposed on them. In this context, Clytemnestra becomes a cry of resistance, breaking centuries of subjugation of feminized bodies.

The character of Agamemnon, far from being a complex hero or an untouchable symbol of glory, is presented as a dictator whose thirst for power and ambition leads him to destroy everyone around him—including himself. This figure resonates with contemporary authoritarian leaders, reminding us that the history of oppression and abuse of power is ongoing. The play itself can be understood as an endless spiral, representing violence that has been constantly reproduced, much like Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring His Son. Agamemnon: The Circle of Blood depicts how these leaders perpetuate a cannibalistic cycle within society, consuming future generations while we admire their energetic might.

A significant detail in the play is the shift from Greek to English, reflecting the reality of many refugees who adopt this language as an essential survival tool. This shift highlights not only the globalization of humanitarian crises but also the paradox of aid that imposes the learning of a language without addressing essential needs.

I have wondered whether Agamemnon: The Circle of Blood is a reimagination or reinterpretation of Aeschylus’s original work. I believe that, in reality, Chawishe brings forth from the depths of history and the collective unconscious the tragedy of the human desire for power and glory. Agamemnon: The Circle of Blood reminds us that change begins with confronting our past and accepting our collective responsibility in the present. The play also vividly demonstrates that we have already been everything: the hero, the leader, the dictator, the murderer, the philosopher, the demon. However, we are all victims of the war machine that seems to be human civilization, which is a tiring way of saying that we have been nothing.

Unless otherwise noted. All photos by Patroklos Skafidas @patroklosskafidas

- Borges, J. L. (1998). The immortal (A. Hurley, Trans.). In Ficciones (pp. 113-141). Grove Press. (Original work published 1947) ↩︎

- La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, at NYC. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.lamama.org/about ↩︎

Rafika Chawishe is an award-winning stage and film actress, director, and passionate children’s rights activist. Known for her impactful work in political and documentary theater, she founded the company Zlap in 2014. Chawishe directed The Mimesis Machine at the National Theatre of Oslo during the Ibsen Festival and won the Ibsen Scholarship Award for a political adaptation of Ibsen’s Little Eyolf. A dedicated advocate for refugee rights, she has worked with unaccompanied minors at the Moria refugee center in Greece, using her art to explore themes of human responsibility and identity. As a filmmaker, her shorts have been showcased at major festivals, including Cannes and Locarno. Chawishe’s stage credits include performances at the National Theater of Greece and Athens Festival, as well as roles in films like Miss Violence and Dance Fight, Love Die.

Concept, Adaptation, Direction and Performance: Rafika Chawishe

Actors: Manos Vakousis (Agamemnon), Rafika Chawishe (Clytemnestra), Chris Radanov (Aegisthus), Samuel Akinola (Herald),Ghada Khayat (Cassandra), Ioanna Angelidi (Lead Chorus) Mustapha Khalfoun (Translator)

Chorus: Addimando Paul, Georgía Abatzoglou, Thanasis Briannas, Akis Karagiannis, Angelitsa Kouloulia, Dimos Lolas, Konstantinos Michalas, Angeliki Papadimitriou, Anny Theodouli, Michalis Theodorakis, Ioanna Zerva

Art Direction & concept : Michalis Argyrou,

Music and Sound Design (Stage & Film):Manolis Manousakis

Video Artist (liquid staging technique) and Film and Text Consultant: Asteris Koutoulas

Dramaturgy: Isabella Sedlak

Costume Design (Stage & Film): Despoina Chimona

Lighting Designer: Melina Mascha

Assistant Lighting Designer : Ismini Starida

Assistant Director: Wichi

Location Recording (Film and Theatre), Recording Mixer: Kostas Stylianou

Lighting Design and DOP (Film): Dionysis Efthimiopoulos

Assistant Director Film: Dimitra Tsialou

DOP Assistant: Stratis Kourlis

Chief Electrician: Vangelis Papadatos

Grip: Giorgos Rigas

Make Up Artist: Maria Braliou

Hair Design: Alexia Karapanou

Prop Manager: Anestina Argyropoulou, Photography (Stage & Film): Patroklos Skafidas

Graphics: Thomas Palivos

Production Consultant: Vicky Strataki / Polypanity Productions,

Communication Manager: Michelle Tabanick

Production and Design (in Greece) byTitania Productions, Daydreams Productions, La MaMa Theatre

Liquid Staging Technique of Asteris Koutoulas

Supported by: The Greek National Tourism Organisation (EOT) and the Municipality of Northern Aegean The film was shot in Athens and on the sandy beaches of the island Lemnos with the support of the North Aegean Region and unde.