By Kekena Corvalán

Katya Cazar is one of Ecuador’s most influential curators and cultural managers. Over the years, she has carved out a career that bridges curatorial practice, art history, and feminist theory. Her commitment to a more inclusive and equitable art world has driven numerous projects that focus on amplifying the voices of women artists and critiquing the hegemonic structures within Ecuador’s and Latin America’s art scenes. With deep knowledge of her country’s socio-political and cultural contexts, Cazar reflects on her work as an artist and curator, alongside her perspectives on the feminist movement in the contemporary art world. “In Ecuador, the lack of unity among women has weakened us as a social and political movement.”

Kekena: I first wanted to ask you about your background and how you came to curate through it.

Katya: Looking back, I can see that many influences and moments shaped my education. I come from a family rooted in science and medicine, so studying art meant breaking with tradition and moving toward a different kind of knowledge. My mother listened to my calling and always encouraged me. I studied painting from a very young age through to high school graduation, and later, I earned a degree in Visual Arts. From there, I remained curious and decided to study Latin American art curation through a very innovative program, although it was quite distant from Ecuador’s reality, offered by the Sofía Imber Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Caracas. I studied under the coordination of María Elena Ramos, a prominent thinker and curator. Caracas, unknowingly at the time, became a fundamental stage for me. I was exposed to facets of the art world completely unknown in Ecuador. Caracas introduced me to the operation of major museum collections, which involve substantial investment in acquisitions and art promotion.

I was also struck by the museum’s pedagogical and social role and the intellectual, sensitive, horizontal, and essential work done by the curators trained there. I had access to remarkable collections—works by foundational artists, from public museums to private collections like the Cisneros Collection—before it was removed from the country during the political upheaval.

Upon returning to Ecuador, I took on one of my first curatorial projects—something I now find both interesting and, in some ways, naïve. The University of Cuenca hired me to commemorate its Jubilee Year 25 or 26 years ago. It was a very enriching experience as I conducted a research project that others have since continued at the university: What happened to the women who studied Fine Arts when the university was founded? How was the Academy structured, and what happened to its female students? In Ecuador, Fine Arts faculties typically have a majority of women students. However, paradoxically, they are the ones who practice the least. The research was eye-opening: subjects were divided by gender and schedule. In the morning, women studied painting, drawing, and gouache; in the afternoon, the “masculine” subjects were taught—sculpture, marble carving, forging, ceramics, and life drawing. That research led to a much broader investigation, which was later exhibited here in Cuenca at the Remigio Crespo Museum, recovering many works that had been part of the university’s heritage.

Katya Cazar.

KC: And how did you weave together your work as a curator and as an artist?

Katya: I developed both careers simultaneously. I have been part of pivotal moments in Ecuadorian art. I co-curated a project that broke with the dominant canon of public art in Ecuador: Contemporary Art in the Courtyards of Quito, alongside Gerardo Mosquera. On an unprecedented scale, it involved fourteen contemporary artists intervening in fourteen historic courtyards of Quito’s Historic Center. It was a massive artistic and logistical feat—never done in Ecuador before. That experience was a prelude to the 11th Cuenca Biennial, which the Municipal Biennial Foundation invited me to curate in 2010. Later, in 2012, I was appointed

as its director, and again in 2023.

It has been a prosperous journey. I’ve never stopped exhibiting, both in solo and group shows. I am also deeply engaged in academic work. I am currently finishing my doctoral thesis. However, academic work must remain sensitive to the real world, as well as to local and global contexts. The Ecuadorian context is highly complex, characterized by deep hierarchy, patriarchy, and political tension. Every act, no matter how personal, is political. Moreover, when politics is controlled by patriarchy, it becomes very complicated. I curated the 12th Biennial, titled Ir para volver (To Go to Return), dedicated to global migration. This topic was profoundly relevant and emotional for a region like Cuenca, where migration has shaped the social landscape since the mid-20th century. The city depends economically on remittances from abroad. Later, as I had more time, I directed the 15th edition of the Biennial with a more sensitive approach. That Biennial featured 37 artists across 12 venues. We produced and financed the entire event—including the catalog—within a year and a half.

The 15th Biennial, “Change Green for Blue,” was centered on ecofeminism, ecology, and ancestral knowledge, and gave historical visibility to women artists. It marked the highest participation of Latin American and Ecuadorian women artists in the event’s 30-year history. We focused on sustainable production models, even in the midst of a pandemic. The invited curator was a woman. These may seem like small gestures, but they are revolutionary in Ecuador’s male-dominated art scene.

I currently work as a freelancer. I left the 16th Biennial halfway through—after appointing the curator, selecting the artists, and designing a management model. However, the conscious and intentional process we’d started was cut short due to political changes. Unfortunately, this upcoming edition of the Biennial has overlooked sensitive and intersectional themes, including women’s presence, feminism, ancestral knowledge, and sustainable production. That is unpleasant because we must never turn our backs on Ecuador’s rich, diverse, and culturally rooted context. Our country is filled with unique voices and diverse knowledge systems. That is what makes us rich, not money, but diversity. And that gives us a unique perspective on the future and contemporary art.

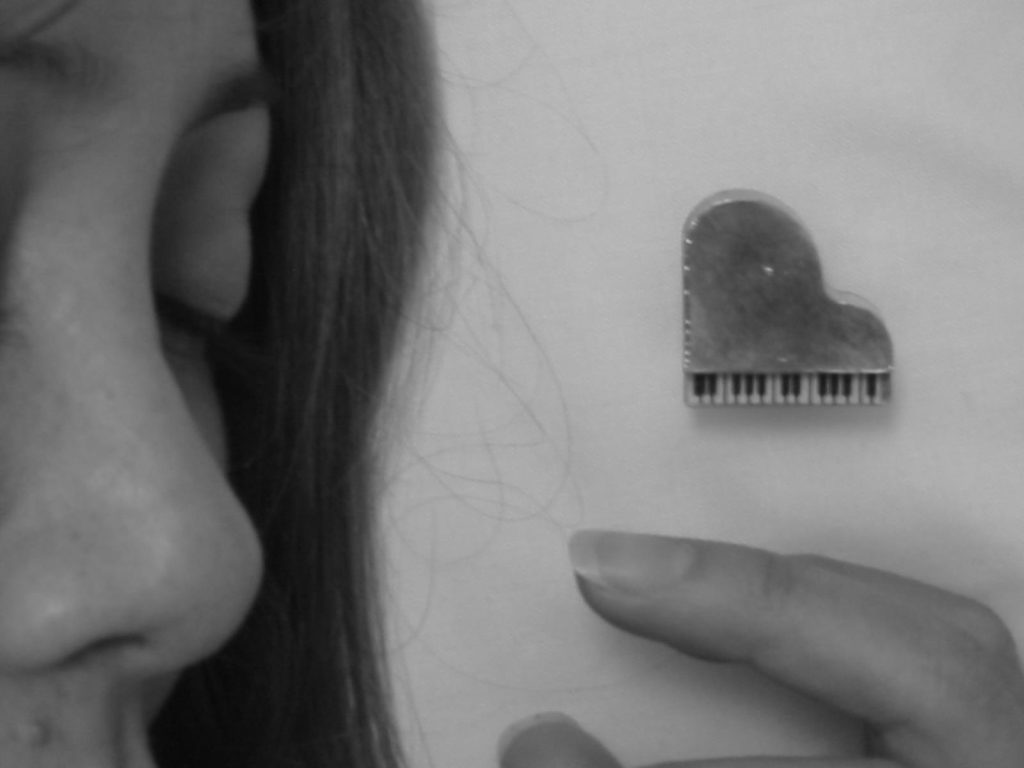

Cazar, K. (2010). Piano [Photograph on paper].

KC: I’d like you to tell me how you see feminist curating today within the framework of this fourth wave, which is nourishing those of us who come from an earlier, perhaps intermediate, wave.

Katya: We are currently deconstructing curatorial practices themselves. It’s no longer about reinforcing hegemonic hierarchies but about building horizontal, democratic, and axial models. We are a network of compañeras who support each other and protect one another, especially in the face of abuse or political decisions driven by machismo. Conceptually, we are in the fourth wave of feminism in Latin America. But in Ecuador, although we are aware of the feminist struggle, we have not yet fully entered that fourth wave, where feminism becomes structurally consolidated. The most significant contribution of feminist curating is visibility: highlighting women artists who are already present and those who are still producing and rescuing forgotten names, lost works, and erased trajectories. That’s the only way to rewrite the narrative of an art history that—in countries like mine—is still told by men from their own subjective viewpoints, not from the real story.

Working with numerous Latin American women artists from diverse generations has been incredibly fulfilling. I fondly remember having Marta Araujo, a contemporary of Ana María Maiolino, at the 12th Cuenca Biennial. She is an artist with a powerful body of work dating back to the Brazilian dictatorship, deeply engaged with the body. Interestingly, she had never left Brazil, and her first international exhibition was in Ecuador. It also excites me to recall working with Priscila Monge, Regina José Galindo, Tania Candiani, and many others. Their presence was an enormous contribution, even if it has not always been given the recognition it deserves. But the testimony remains in the catalogs, which were the most affordable in the Biennial’s history. That is evidence of feminine care that values diverse economies and sustainable models.

It is urgent to support the visibility of women artists, curators, and cultural workers. Women’s careers in the art world are often cut short, so documenting and safeguarding women’s historiographies is a crucial responsibility. In my case, I have been an artist, curator, and cultural manager. That means navigating political power dynamics and engaging in negotiations that seek the common good, always with rigor and care. Most importantly, it means staying vigilant, ensuring that the processes led by women, both artists and organizers, can be carried through without censorship.

Cazar, K. (2008). Repetition [Photograph on paper].

KC: And if I told you that we need to think about strategies of decompeting, what comes to mind

Katya: I think that’s something urgent. Because if we go back to competing, we fall right back into the patriarchal canon. The only way to become more powerful is to stand together—collectively and generously—promoting collaboration, engaging in constant dialogue, and being a strategic force.

KC: When it comes to your work as an artist, what moves you?

Katya: For many years, I focused heavily on the theme of self-representation, driven by the sheer panic I felt when photographing myself or seeing myself in photographs. It was a profound process of accepting my body and my memories. I created large-scale pictures, like a banner I installed at the 7th Cuenca Biennial, which covered the entire Municipal Palace. That piece is a dialogue with myself about the idea of lying—how often we lie to ourselves to present ourselves, and how much we manipulate our image in pursuit of beauty and societal standards.

I’ve explored many aspects of emotional life and the domestic space as a battlefield, in response to the social establishment of a conservative Andean country. More recently, I’ve become deeply interested in historical narratives. My latest solo exhibition is dedicated to my daughters, because motherhood is such a powerful subject, filled with both light and shadow. I’ve dedicated the work to the idea of duality, to the definition of the in-dividual—a doubled being, with folds within folds. It’s also about how motherhood influences our intellectual and formal output, while at the same time serving as a great source of inspiration.

It’s also a critique of a system that still frames exhibitions primarily for men, without acknowledging that many of us working in the arts and culture are mothers—we run households, we’re heads of families. And when we travel for work, there’s an entire other system that must continue functioning in our absence. Currently, I am interested in the patriarchal image of various historical Ecuadorian heroes. I’m intervening in a series of books and photographs—finger books, film books—creating actions to present them in international contexts. These works are designed to confront the great male hierarchs who have shaped and continue to shape the official narrative of our history.

Cazar, K. (2023). The Double [Photograph on paper].

KC: To wrap up—why is it so hard for Ecuadorian women artists to be seen on the world stage?

Katya: I believe there are good women artists—there may not be many, but they’re out there, navigating the ambiguity of life and artistic work, often without much support. That lack of support starts at home, in the emotional and relational sphere, and extends to institutional backing. There’s no ongoing, structured system of support. What is popular right now is supporting emerging artists—which is important, no doubt—but when it comes to the production of art by women, it’s crucial to reexamine how long-term support is granted. Otherwise, women’s lives and their responsibilities slowly chip away at their opportunities for work and visibility.

We have long been a minority, so it is essential to focus on positioning, management, and dissemination. Ecuador has an excellent museum system—most are heritage-based, which is great in one sense; however, the internal administrative systems and platforms are outdated. Investment needs to grow—it cannot continue at the current pace. We’ve made some progress, but it remains extremely challenging in terms of funding and representation, particularly in terms of global visibility. The Cuenca Biennial has played a key role in that, and it must continue to be a responsible player in both the national and local art scenes. If not, we’ll always be falling behind—we always value the outside world more, even though there’s so much to be said about Ecuador itself.

It’s a country with a considerable debt to contemporary art. While there has been some support, it’s not enough. The support system needs to be nourished, and the work with minorities reevaluated—especially women, who are among the most in need. Tribute shows or March 8th events aren’t enough. We need deeper reflection. Local and national governments, along with various institutions, must step up and offer more technical, sustainable, and long-term support, with less short-term thinking and fewer stopgap policies.

Cazar, K. (2007). Lie [Mixed media].

KC: It would be beautiful to have a woman president, wouldn’t it?

Katya: Yes, absolutely! Without a doubt. Just as having women ministers, assembly members, councilwomen, and museum directors empowers women artists to live dignified lives and continue creating art.