Yasodari Sánchez in Conversation with Rocío Cárdenas”

By Rocío Cárdenas

In the Riverbed / Yasodari Sánchez MARCO Museum of Contemporary Art

Mty. NL. May 31–September 1, 2024.

RC: Rocío Cárdenas

YS: Yasodari Sánchez

RC: How does your work with Central American and Indigenous migrant communities contribute to resisting oppression?

YS: I have always believed that art is a device for communicating diverse disciplines. My work as an artist has centered on supporting communities and various collectives that, through other forms of action, remain trapped in cycles of normalized precarity, violence, and misery. This is because dialogues stemming from social work, civic services, or NGOs that serve migrants often fall short of offering comprehensive support.

Community art expresses different ways in which the circumstances of migration have transformed both human and artistic practices. I say this based on nearly 15 years of experience working with migrants in the urban area of Monterrey, Nuevo León, in northeastern Mexico.

For me, the first action through art is to recognize individuals’ human rights, dignify them, and share in their migration journey, to talk with them, tell them my life story, share meals, celebrations, funerals, farewells, and losses—in short, get to know one another. Migration is a continuous flow—sometimes high, sometimes low—but it never disappears.

A key factor is that migratory states constantly bring us diverse forms of knowledge that cannot be approached through a linear reading. On the contrary, human migrations are multidimensional and global.

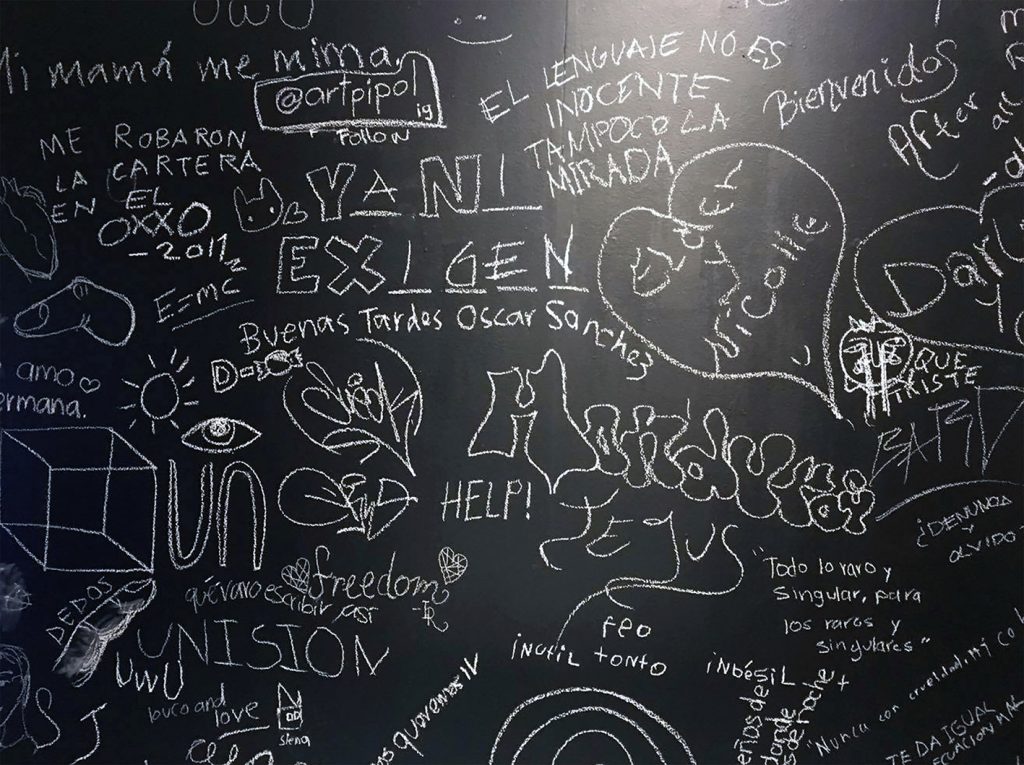

Sonidero mural in a public space. San Luisito Market. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation. 2021

RC: How have migration patterns changed, particularly for women, in recent years?

YS: My experience related to contemporary migration, when I have analyzed and accompanied, has moved away from the distant historical chronicles tucked into family memory chests. Migration has changed in form and the nature of receiving populations, altering their logic and practices in Monterrey’s urban setting. It now confronts harsh realities like racism, violence, machismo, and xenophobia.

When I worked with different Central American migrant populations about twelve years ago, I realized that what I knew about migration was far from the experience. There was no trace or record of women as migrants.

The prevailing sociological bias was that migrants were only men—only men undertook the journey or the adventure—while women were excluded from that narrative and reality. In 2013, we published the first report on Central American migrant women in the city. Usually, there were no academic studies or research (from sociologists, anthropologists, or social workers) addressing women’s immigration.

Our first step was to make migrant women visible—women who were part of a different kind of migratory flow and had a range of needs upon arriving in the city. We realized (and while this may sound simple now, it was important at the time) what it meant to come alone or as part of a migrant caravan as a woman: facing dangers along the way—sexual violence, theft, abuse, misogyny—along with exclusion and rejection from migrant shelters (most of which were run by Catholic associations). It was essential to develop new strategies for safety and support.

One of the key findings in the report was that migrant women supported one another even before beginning their journeys. They had formed a precarious yet crucial support network in which they shared what to do in cases of sexual assault or pregnancy during the journey. Many arrived in Monterrey in the advanced stages of pregnancy and needed access to medical services for childbirth. We collaborated with the law school to offer legal support, helping these women access healthcare and register their babies as Mexican citizens.

Over ten years ago, the city was under different conditions. There were fewer migrants—there had not been a Haitian migration yet. Most migrant women were Central American, primarily Honduran and Salvadoran.

Nicolás Migrant House, Guadalupe, Nuevo León. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation. 2012.

Another initiative we pursued was creating a map of potential employers who could hire these women. Some arrived with small children, and their only option for entertaining them was taking them to the park. At migrant shelters like Casa Nicolás, they were let out at 7:00 a.m. If the mothers had to work (whatever jobs they could find), their children stayed in the park until 5:00 p.m., when the shelter reopened. Casa del Forastero did not accept women. Some would ask for money on the streets and look out for one another.

At that time, our artistic practices aimed to find new ways to explain their human rights—to show them they could enroll their children in the state education system and that they had access to education. We accompanied them in learning about the obligations of the Mexican state.

These experiences showed me that any community-based approach—especially with women in such complex situations—must be built on sensitivity and humanity, not just statistics. I led photography workshops for the children, organized games, and sometimes researched memory-related topics from their hometowns (which they refer to as “departments”). I remember the $20.00 pesos phone cards we raffled off. I would ask simple questions, and after their calls home, I would ask them to share a snippet of their conversation.

There was a public phone always surrounded by people in line. I remember that experience fondly—we laughed a lot during the trivia games, and everyone had a good time.

Another area I worked on with them was food. They did not like the local cuisine and formed a community around what they ate, so I set out to find the ingredients they needed to cook their traditional dishes. They organized dinners and gatherings—powerful moments for building friendship and sharing.

Nicolás Migrant House, Guadalupe, Nuevo León. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation. 2012.

RC: Why didn’t Honduran migrants in Monterrey build a community?

YS: That has to do with the circumstances of that time. First, the precarious conditions they arrived in. It is not like the migration of Indigenous women from within Mexico—they had to be extremely cautious about where they lived and whether the space was safe, mainly due to their undocumented status.

Second, they did not go out much and could not build community. Outings were in pairs or groups of three, and they spoke as little as possible, carefully hiding their accent (in Spanish). They feared Mexican immigration agents. If stopped, they would say they were from Veracruz. Many memorized the national anthem and the biographies of key revolutionary figures.

I had many encounters with the police in Guadalupe (a municipality in the Monterrey urban area), with a large Honduran population. The police often extorted them. So, the migration conditions for Central American women were very different compared to Mixtec Indigenous women migrating to Monterrey.

RC: Can you tell us about your work as an artist with Indigenous women’s communities in urban areas of Monterrey, Nuevo León?

YS: I started working mainly with Mixtec and Nahua Indigenous women in 2013. Unlike other migrants, they needed to gather together—it’s a cultural issue. Upon arriving in the city, they would seek out family, either blood or chosen.

Their community building centered on practices like cooking, embroidery, and celebrating religious dates from their places of origin. For example, in February, they celebrate the Señor de Chahuatlán. These migrants come from the Huasteca Hidalguense region, where the states of Veracruz, Hidalgo, and Zacatecas converge.

I have been attending their local celebration in Monterrey for about twelve years. They gather for the event here in the city—returning to their villages is not always possible. They hire music groups from their communities; it is a highly musical culture. There are even flirtations and romances among women who meet young men from other villages in the Imatlán region—right here in Monterrey, especially at Mariano Escobedo Plaza, known as La Alameda, in the city center.

Their intercommunity relationships, especially between men and women, are very different. That’s when I realized again how important it is to know the numbers—the complex data—about how many Indigenous women migrate to Monterrey for life, work, and education. Even more importantly, we must be sensitive to the knowledge they bring from their communities.

Golden Ace Band. Mixtec community in the Héctor Caballero neighborhood, Villa de Juárez, Nuevo León. Yasodari Sánchez archive and documentation. 2023.

RC: Tell me about your work titled Mano de Obra (Workforce).

YS:

I created that piece with a specific focus on how we label the “workforce” of Central American migrants—how we identify them through their fingerprints, but also in connection with particular cases of kidnapping that occurred at Casa Nicolás, a migrant shelter, and in the municipality of Guadalupe, particularly involving Hondurans. After these disappearances, there was no further information. Their labor is literal, but their fingerprints also symbolize each person’s unique identity. That’s why I decided to take samples from their fingers—fingerprints turned into small sculptures that, from afar, resembled pieces of school chalk.

Labor and Manpower Indexes. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation. 2017.

Later, I made those pieces in “ID size.” I think by now it’s clear that the condition of migrant women is even more precarious than that of men. I remember that at the time, Central American women were being hired by a company that washed plastic; one of them developed a fungal infection on her arms due to the accumulated dust. They had no health insurance and were paid just 40 pesos a day, working from 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. By contrast, a Central American man would be paid 100 pesos a day (still a very low wage), but the difference was significant.

Another thing we noticed in the report was that not many employers were hiring women. This made us think the demand was more for men and heavy labor.

Index fingers of Hand and Work. Archive and documentation of Yasodari Sánchez. 2017.

RC: Can we talk about the differences between Central American and Indigenous migrants regarding how they adapt to urban communities?

YS:

It’s essential to recognize that for an urban Indigenous person to feel secure and integrated when arriving in Monterrey, many things had to happen—including transformation processes. Even though, according to official government data, the state of Nuevo León was named the most discriminatory in the country in 2015, the most significant wave of Indigenous migration occurred in the 1990s. That was when Nahua families arrived in the Río La Silla area, located in the southern part of the city between Monterrey and Guadalupe. They found landscapes similar to those in Veracruz and arrived in large family groups, which allowed them to settle with some level of population security—housing, land, and work—resources that many Central American migrants never gain access to.

Indigenous migrants in this area have now built families over nearly 40 years and are entering their third or fourth generation. In contrast, Central American migrants arrive believing this will be a temporary stop, only to end up staying because they are unable to cross into the United States. Even worse, women are often abandoned by their male partners—who return to Honduras or El Salvador—leaving them alone with their children. There is no family-building, much less any formation of community.

In the 1990s, the presence of Central American migrants wasn’t as significant as it is today. Drug cartels, organized crime, and the violence along the border—especially in Matamoros, Reynosa, and Piedras Negras—lead many to return to Monterrey despite the discrimination and difficulties, because it’s still a safer place to live and offers employment.

That’s why many end up staying. Monterrey and its greater metropolitan area are large cities with nearly 7 million people so they can blend in. They buy counterfeit brand clothing at the markets and say they’re from Veracruz or Tabasco, regions they passed through during their journey, so that they can pass as domestic migrants.

From all this, I created a medium-length documentary titled A corto plazo (In the Short Term) about Central American migration in the city.

Also, I want to note that women have given voice to other women—in this case, migrant women. For example, Séverine Durin, a CIESAS-Northeast researcher, studied domestic labor in Monterrey. Alongside her, I also interviewed Hiroko Asakura, a Japanese anthropologist living in Monterrey. These are foreign women anthropologists working to bring visibility to migration issues in Monterrey.

Later, other institutions emerged, such as Zihuame Mochila AC with Carmen Farías and Zihuakalli: Casa de las Mujeres Indígenas with Elvira Maya, Gabriela Hernández, Jesusita Mendoza, Reyna and Lili Patricio, and Julieta Martínez—to name a few—from different Indigenous communities. They began generating economic initiatives and conversations, seeking government support for entrepreneurship and self-employment. During this time, I began to work mainly with Indigenous women.

I discovered clear differences among various groups of Indigenous migrant women. For instance, in the Nahua community, there were many patriarchal and macho traditions, but these women resisted through community matriarchies. They would negotiate with men to access support such as PACMYC grants or government scholarships. This was very different from what I observed among Mixtec women, who couldn’t reach such agreements—Mixtec men were the ones making all the decisions.

Lucia and Mariela. Otomi Community, Lomas Modelo. Monterrey, Nuevo León. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation.

RC: In what ways do these communal actions influence and connect to your own life experience?

YS:

These seemingly simple acts—like embroidery—affirm my roots and my desire to work in public spaces. I’ve always been engaged with reflecting on migration flows and participating in their practices. For example, I once helped Central American women prepare their traditional dishes. It took me five hours just to find green plantains and cooking bananas. Ten years ago, those ingredients weren’t easy to find. Now, you go to HEB and find plantain leaves and all their spices. It might seem trivial, but the economic system capitalizes on every consumption gap—including that of migrants—without formally incorporating them into the economy. These migrants are already participating in global consumption.

Food monopolies acknowledge the needs of minority communities and update their offerings accordingly. For instance, I’m amazed to see tamales wrapped in plantain leaves being sold—items that used to be foreign to local cuisine are now part of everyday life. These products used to be found only in leisure spaces for migrants, like Alameda Mariano Escobedo Park or public markets. Now they’re sold in regular supermarkets, like tamales veracruzanos. All this knowledge sustains Indigenous migrant women. They make and sell tamales, generating income organically.

Green as a Tamale Leaf. Selected for the Second State Art Prize in Nuevo León, with honorable mention. Yasodari Sánchez archive and documentation. 2020.

Green Like a Tamal Leaf is a piece I created where the voice of women is often represented within specific circuits. There are colors—within the feminist movement, for instance—that symbolize women, like green and purple. That’s why I saw Nahua women as having a deep consciousness of autonomy; one could say a powerful will to move forward. Moreover, they possess knowledge fully integrated into their lives and self-employment practices. It strikes me that they do not rely on protests or formal petitions typically associated with feminist movements. Without minimizing the critical accomplishments of public policies and support systems for women and various collectives, I see that these women, as a community, are powerful and resilient in the face of present-day change.

The way they carry out these actions—from symbolic micro-economies to the economies of embroidery and festivities—is remarkable. They braid their hair and know how to style it. They also have urban milpa projects, growing beans, squash, and fava beans—crops that naturally nourish their families. They used the phrases in Nahuatl and connected directly to their personal and cultural context. I asked them to embroider these phrases in white. Traditionally, their embroidery draws from memories of landscapes, animals, and flowers. But more recently, many have shifted to commercial images like Spider-Man, Mini Mickey Mouse, or SpongeBob SquarePants—figures that can be sold.

Verde como la Hoja de Tamal. Seleccionada en el Segundo Premio Estatal de Arte Nuevo León, con mención honorífica. Archivo y documentación de Yasodari Sánchez. 2020.

At that moment, however, the Nahua women did not want to embroider in white; they did not understand why. There’s a specific boundary from which they cannot leap into abrupt shifts or undertake custom requests like mine. By contrast, the Mixtec women were open to embroidering. In a different way, the Mixtec women understand their knowledge systems better. They are more attuned to interdisciplinary work and more open to study and crafting, like embroidery.

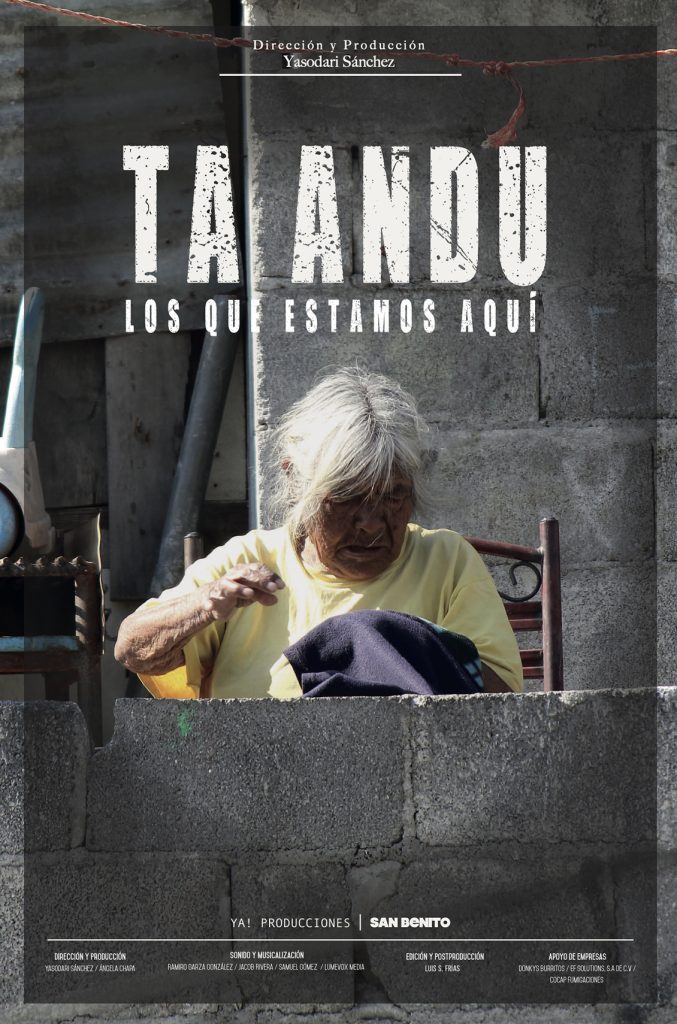

Their primary craft is weaving with natural palm and plastic. When they arrived in Monterrey, they did not know how to embroider. But city dwellers assumed that any Indigenous woman, by her origin, knew how. So, the women saw this as a work opportunity, a way to build an economy, and they learned. These are two distinct strategies. Even though Mixtec women carry heavier patriarchal burdens, they still generate income and social strategies beyond their community. These reflections led me to create the feature-length documentary TAANDU: Los que estamos aquí (“We Who Are Here”), about Indigenous migration in the Monterrey metropolitan area.

Another interesting fact is that Mixtec women organized Monterrey’s first matachines (ritual dance) group. One of their leaders, Jesusa, founded this group with Mixtec girls and teenagers. They even offered this dance as a tribute during the celebrations of San Andrés in Oaxaca. I also found it striking that they began cutting their hair, breaking the mold of what a “Mixtec woman” was expected to be. They are a powerful example for other women. For instance, Señora Reyna was the first Mixtec woman to wear pants in 1990. We can imagine many things, but the reality of arriving in a city like Monterrey, being forcibly relocated from the banks of the Río La Silla in a garbage truck, and then sent to live in the Héctor Caballero neighborhood—that was a different Monterrey altogether. Now, the new generations of urban Indigenous people—some already in their third generation—no longer speak Nahuatl, Mixtec, or Tzotzil. Shame and fear of discrimination have silenced those tongues.

Taandu. Those of Us Who Are Here. Produced and Directed by Yasodari Sánchez. Selected for the Monterrey International Film Festival. Yasodari Sánchez Archive and Documentation. 2015.