By Yohanna Magdalene Roa

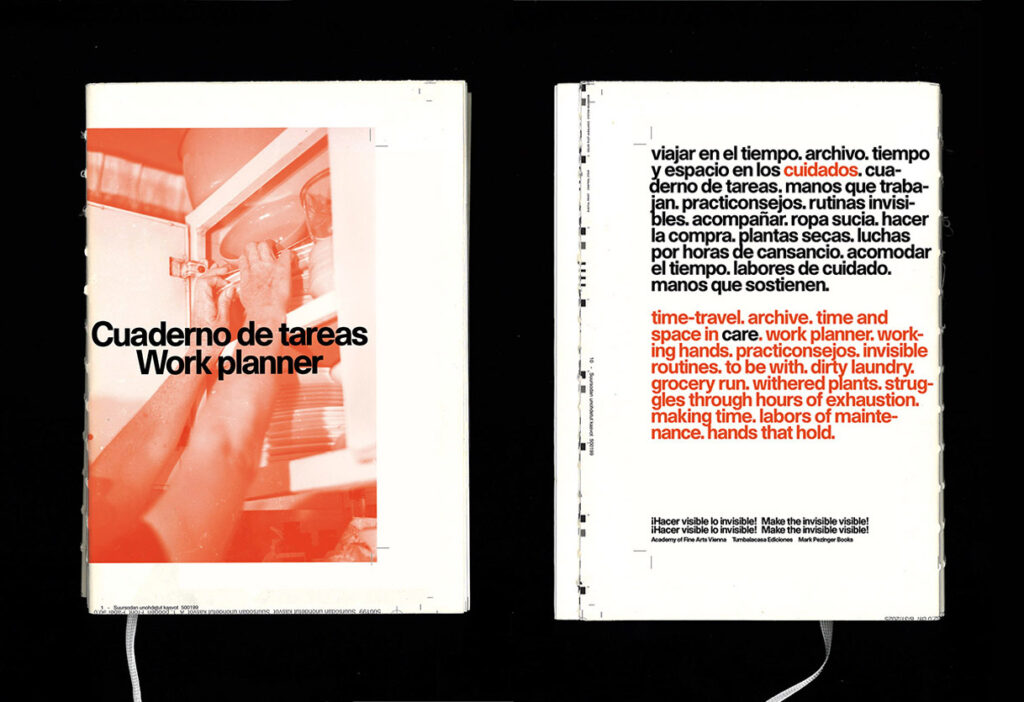

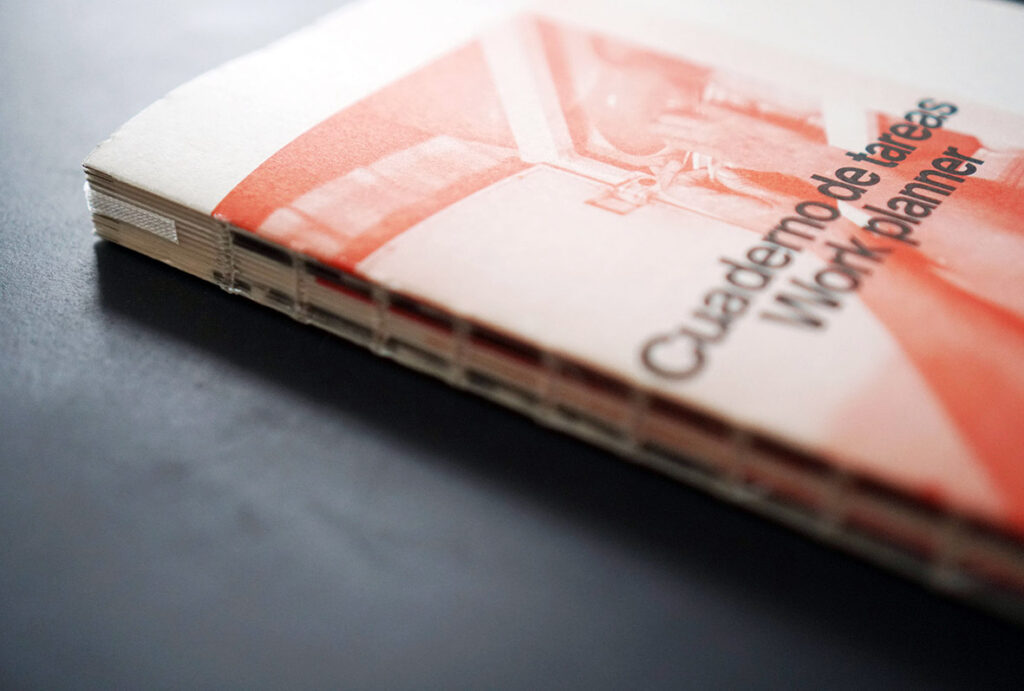

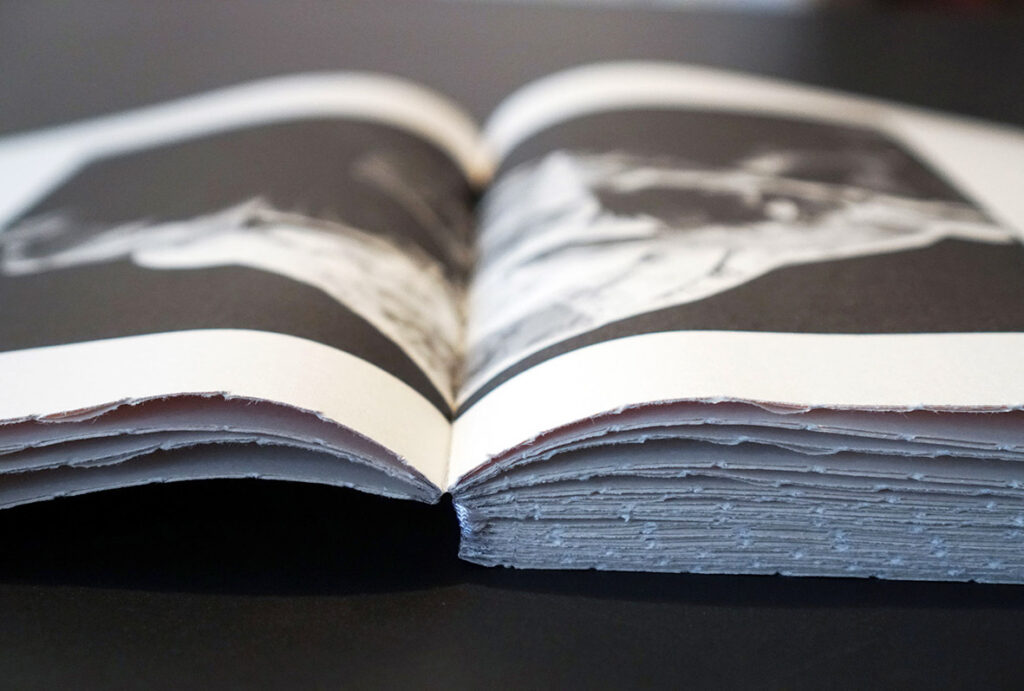

There is something profoundly unsettling, in the best sense, about opening a book and discovering it is not finished. Not because it is incomplete, but because it expects something from us. Cuaderno de tareas / Work planner, published by Tumbalacasa Ediciones in collaboration with Mark Pezinger Books and the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna as part of the Fine Companions series, appears as a slight wound, a fold still sealed. The pages are not open. They are not trimmed. They are not domesticated. To read it, one must insert a hand from below and separate the upper seams. One must press gently. One must touch.

And in that minimal, insistent gesture… the book has already begun to speak.

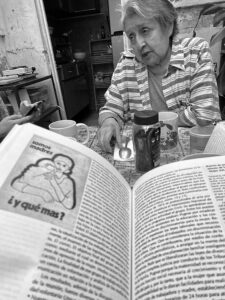

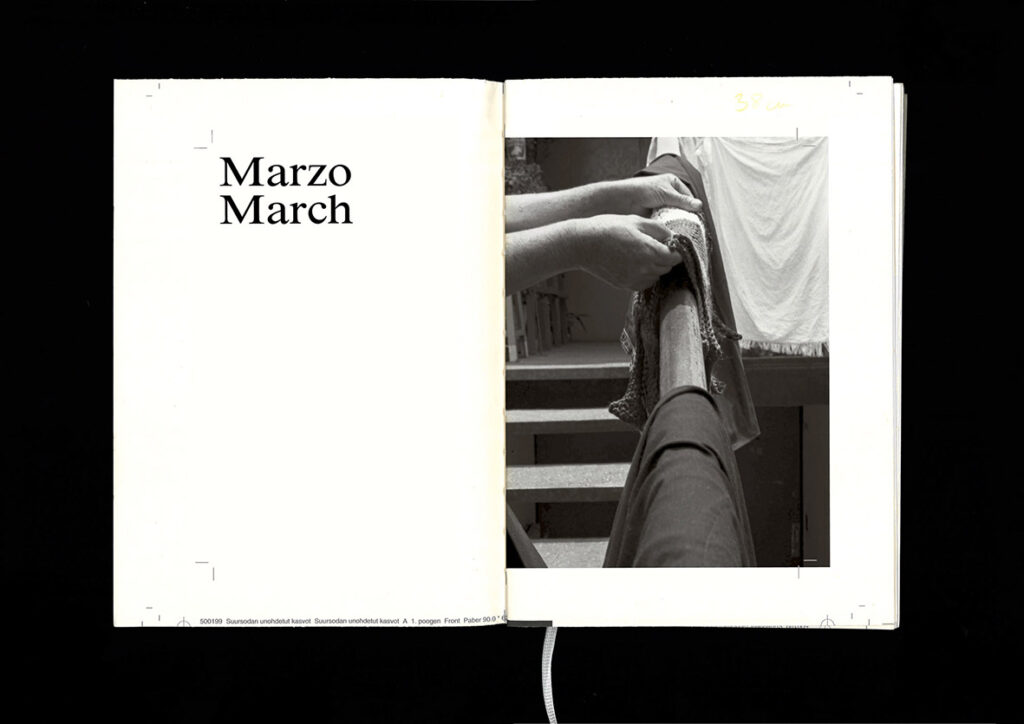

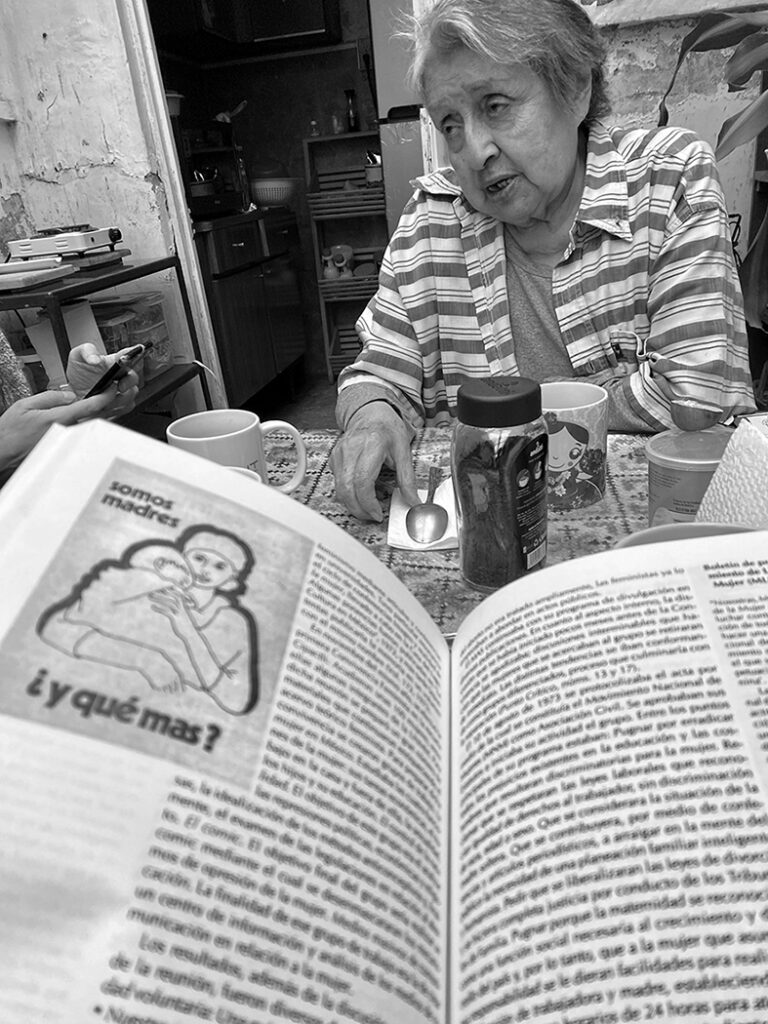

The original project was conceived between 1978 and 1981, when Ana Victoria was photographing hands. Not faces. Not full scenes. Hands. Hands that cook, that hand-wash clothes, that fold, that sew, that write. Hands in repetition. Hands that sustain the day while the day refuses to acknowledge them.

Ana Victoria was born in 1941 in Mexico City. Her political life began in the 1960s, when she joined the Mexican Communist Party. She left after confronting its patriarchal structures. She did not withdraw from politics; she shifted its ground. She turned toward organized feminism, co-founding the National Union of Mexican Women, participating in Women in Solidarity Action, and later, in 1984, founding Tlacuilas y Retrateras, a feminist art collective.

Her archive comprises more than 8,700 materials, documents protests, gatherings, marches, and everyday gestures of resistance across Mexico and Latin America. There, feminism does not appear as an abstraction but as situated practice: body, street, slogan, care. Cuaderno de tareas emerges from this political and personal weave.

The photographic series was originally intended to become a planner for Colectivo Atabal, a civil association founded in 1987 by feminist women to recognize and value housework. It was conceived as a concrete tool. A planner in which domestic workers could record their days, document their tasks, reclaim their time.

Training in labor rights, practiconsejos (practical-advice), job boards, political education: Atabal insisted on something that still unsettles today — that domestic labor IS labor. That time spent sustaining life is not empty time. That care is not feminine nature but economic structure.

As one banner preserved in the archive declared: Housework time IS time and IS work.

The book could not be published at the time. Lack of resources. Lack of conditions. Decades later — following a direct request from Ana Victoria Jiménez, who around 2018 asked Nina Hoechtl to take up and edit the planner — Nina Hoechtl and Andrea Ancira return to the archive, now housed at the Francisco Xavier Clavigero Library at Universidad Iberoamericana and recognized by UNESCO. They encounter this suspended project and reactivate it as a question, not as a relic.

Who organizes time?

Who measures it?

Who decides what counts as work?

What friction arises when the time of care collides with the time of capital?

Cuaderno de tareas responds through materiality.

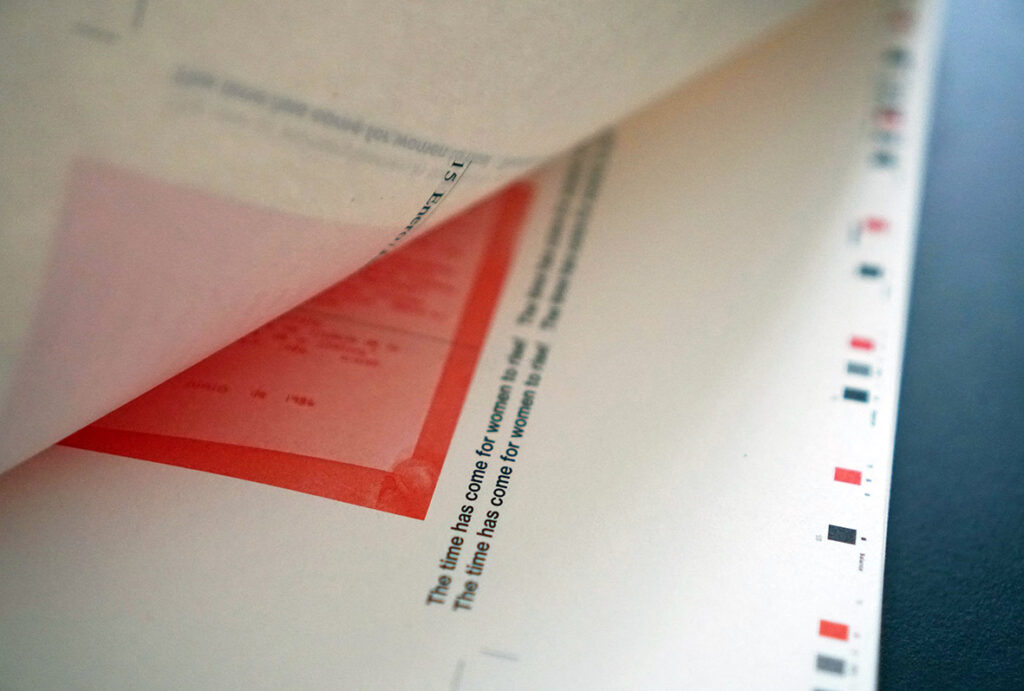

The volume appears in raw form. Untrimmed. Unfinished. Without concealing the evidence of the editorial process. The pages are sealed. The book reveals the invisible labor of bookmaking in the same way the photographs revealed the invisible labor of sustaining households. The parallel is not illustrative; it is structural.

The sealed pages compel the reader to intervene. Reading becomes an act. To stroke the lower edge, to separate carefully, to open the seam: this gesture mirrors what the images once recorded. If the photographed hands sustained domestic time, our hands now sustain the archive. What might seem like a formal detail becomes an ethics of contact.

The planner has no fixed year; it can begin at any moment. It invites us to inhabit a discontinuous, immeasurable time — woven outside the logic of control and efficiency, yet sustained by the invisible hands of care labor. It does not administer productivity; it enables inscription. Along its margins appear phrases and slogans drawn from the archive. Echoes crossing decades. Reminders that reproductive labor sustains not only households but archives, movements, and memories.

For reproductive labor also sustains the archive itself. Not only as content, hands, tasks, but also as a condition of possibility. Care work rarely leaves a trace, yet it makes possible both archives and the worlds we inhabit.

There is something else that pulses within this book: Ana Victoria was able to see the final PDF before her death. She did not hold the printed proof, but she knew the project had found form. That detail is not anecdotal. It reconfigures the object’s temporality. The book is posthumous and not. It is closure and continuation. It is an archive that returns to its author before becoming a public object.

The publication is part of Fine Companions, a series by the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna that interrogates what a book is beyond its text. Here, the question extends:

What is a book when it demands to be opened by hand?

What is a book when reading becomes a gesture of care?

What is a book when it destabilizes the hierarchy between visible and invisible labor?

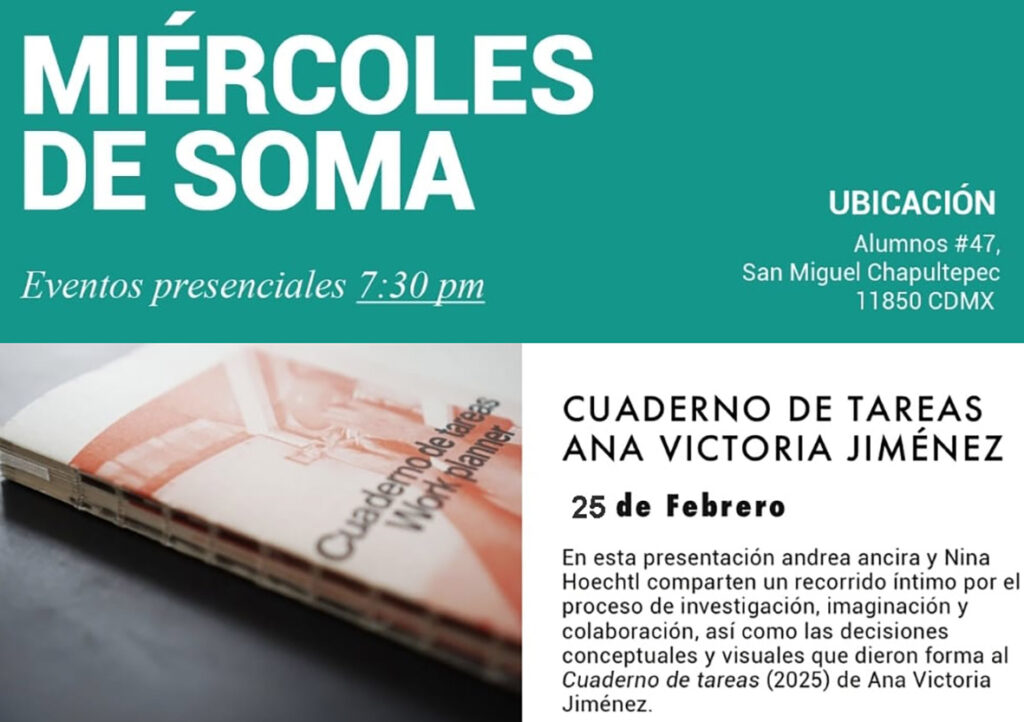

The project has already been presented in Vienna and and in Guatemala City at La revuelta espacio de arte, and will be presented on February 25 at SOMA, Mexico City. The return matters — not as homage, but as circular displacement. The book returns to the territory where the photographs were taken, where the struggle for recognition of domestic labor continues, where housework remains largely informal, precarious, and without full rights. Today, organizations such as CACEH carry that struggle forward. The planner that could not be published in the 1980s re-emerges now as a critical object in the present.

The book does not ask to be read. It asks to be touched. It asks that our own hands interrupt its surface with the record of our daily tasks. To open its pages is to open a question about how we inhabit time. To separate its folds is to acknowledge that invisible labor was never absent; it was simply omitted.

Cuaderno de tareas is not a planner for organizing life. It is a device for unsettling the hierarchy of the visible.

* To acquire Cuaderno de tareas / Work planner in Latin America or the United States, please contact: tumbalacasaediciones@gmail.com Direct inquiries will ensure availability and distribution details for your region.

- Images credits:

andrea ancira, Nina Hoechtl, Ana Victoria Jiménez: Cuaderno de tareas / Work planner

Open-thread binding, uncut, uncovered, ribbon bookmark, 160 × 225 mm, 192 pages

Languages: English/Spanish, edition: 700, design: Astrid Seme, 2025

ISBN: 978-3-903353-24-4

Series: Fine Companions No.3, icw Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Co-published by Tumbalacasa, Mexico-City