Trans – Europe Column

By Nekane Aramburu

“When I die, I will never be able to keep silent again”. —Jean Cocteau

Tanning D. Birthday, 1942. Oil on canvas, 102.2 × 64.8 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. 125th Anniversary Acquisition. Purchased with funds contributed by C. K. Williams, II, 1999. INV. No. 1999-50-1. © Dorothéa Tanning; VEGAP, Madrid, 2025. Photo: Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art ©Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Just when cultural consumers began to believe that everything had already been said or seen, a new wave of revisions of the Surrealist movement emerges, breathing new life into the monotonous landscape of thematic exhibitions. These renewed perspectives enable us to activate overlooked trajectories, delve deeper into ever-suggestive currents, and rediscover old glories from the annals of art history.

Commemorations and anniversaries—a somewhat stale resource—continue to fuel the gears of cultural capitalism. However, everything changes when the reason for celebration is the centenary of writing the first Surrealist manifesto, launched by André Breton in 1924. A broad horizon of infinite possibilities opens up, mobilizing a kaleidoscope of exchanges as versatile and current as the openings of the unconscious, and as diverse as the regions in which these gestures developed or were reinterpreted. Iconic objects and images acquire new gestures and meanings amid today’s pre-AI iconographic whirlwind. Although the term Surréalisme (Surrealism) was used as early as 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire and finds its roots in The Songs

of Maldoror, a work published in 1869 by the Count of Lautréamont, Breton’s foundational manuscript laid the groundwork for a series of approaches advocating the liberation of desire through techniques that reproduced the mechanisms of dreams and psychic automatism.

The first Surrealist exhibition took place in 1925, although not until the 1930s did their group shows acquire a true sense of collective identity. The exhibitions presented in celebration of the centenary of the Manifesto have varied according to the organizing institutions, each entrusting the curatorial concept to different specialists. Based on this curatorial flexibility, the project has traveled to various venues: it was shown in Brussels at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (from February 21 to July 21, 2024), is currently at the Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid (until May 11), will pass through the Centre Pompidou in Paris (from September 4, 2024

to January 13, 2025), and will subsequently reach the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg (from June 13 to October 12, 2025) and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the United States (from November 2025 to February 2026).

Breton, A. Entrée de médiums, 1922. Photo: Nekane Aramburu.

It is well known that Surrealism not only produced iconic works of the 20th century but also generated a vast amount of documentary material oscillating between individual authorship and collective creation. Amid the interplay of foundational works and innovations presented at each venue, some reflections can be drawn—reflections I will attempt to outline in this brief review. I will focus mainly on the approaches developed in Paris and Madrid, whose formal resolutions exhibit both converging elements and complementary solutions: a persistent emphasis on mediumship, the inclusion of creators beyond the European core, the need to map geographically and re-signify artists not typically recognized as Surrealists, as well as the commitment to

making women artists visible.

Varo, R. Icono, 1945. Oil painting, mother-of-pearl inlays, and gold leaf on wood. Closed: 60 × 38.2 × 35 cm / open: 60 × 70 × 35 cm. MALBA Collection. Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires. INV. No.: 1997.02 © Remedios Varo; VEGAP, Madrid, 2025 Photo: Nicolás Beraza.

As a seminal incunabulum, Breton’s manuscript is currently housed in the François Mitterrand branch of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris and was the centerpiece of the scenography at the Centre Pompidou, envisioned as a great resonance chamber that included Breton’s voice recreated through artificial intelligence and projected via a multimedia installation. At the Pompidou, the half-century of research (from 1924 to 1969) conducted by curators Didier Ottinger and Marie Sarré was rendered through theatrical devices and a

labyrinthine itinerary, overwhelming due to the sheer volume of artworks and documents arranged both chronologically and thematically. Visitors, who needed an appointment during peak attendance, could wander through 14 thematic chapters referencing both literary figures who inspired the movement (Lautréamont, Lewis Carroll, Sade, etc.) and the poetic principles that structured its imaginary.

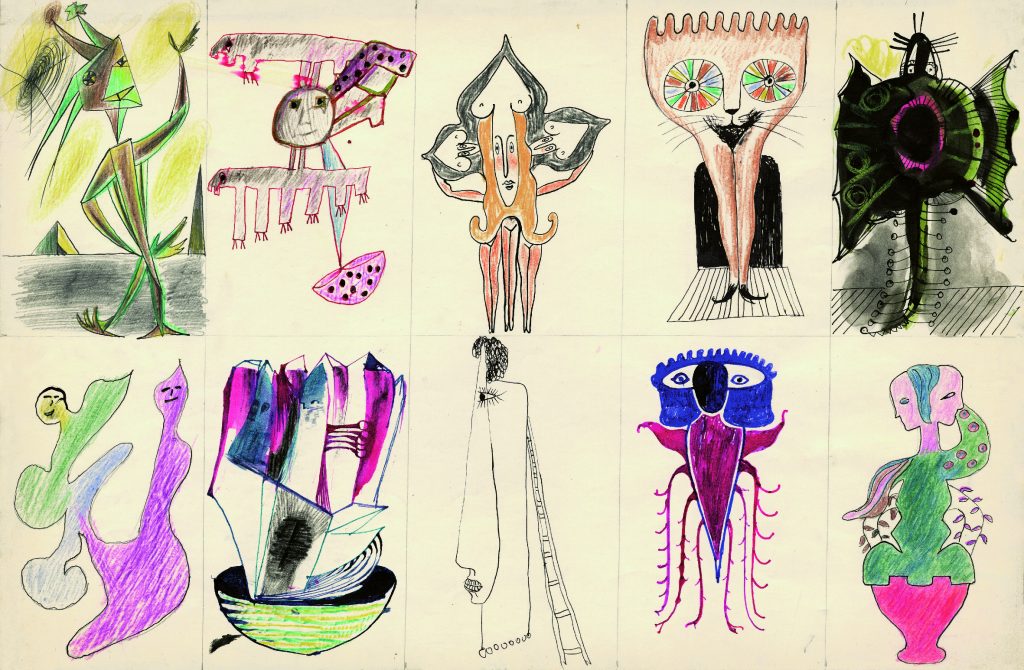

Domínguez, O.; Breton, A.; Brauner, V.; Herold, J.; Varo, R.; Lamba, J.; Lam, W. Collective drawing, 1941, Ink on paper, 32 × 48 cm, TEA Tenerife Arts Space. Tenerife Island Council. Madrid-Paris, 2025.

The first chapter, titled Entrée des médiums—citing a text published by Breton in 1922 in the magazine Littérature, where the mediumnic dimension of Surrealism was first suggested—relies on a now widespread cliché: mediumship is the domain of women artists (Françoise Fondrillon, Unica Zürn, Maruja Mallo, Remedios Varo, Ithell Colquhoun, etc.). However, beyond these tropes about feminine visionariness, the singular language of sculptor Maria Martins is worth recalling, with Prométhée (1948) in Paris and Like a Vine (1946) in Madrid. Also notable was Dorothea Tanning’s imposing installation Chambre 202. Hôtel du Pavot (1970), from the

Pompidou collection.

Tanning, D. Room 202, Hôtel du Pavot, 1970. Wood, fabrics, wool, wallpaper, carpets, light bulbs. 343 x 310 x 470 cm. Centre Pompidou. Photo: Nekane Aramburu.

In both Madrid and Paris, Tanning’s painting Birthday (1942), owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, resonates in dialogue with other iconic pieces. Once the exhibition concludes, what remains is not only the catalog but also the exploratory research on Surrealist Paris from 1920 to 1961 (galleries, studios, cafés, etc.), in contrast with the Cartography in Decolonial Times, based on the Belgian magazine Variétés (1929), conceived for the Madrid edition, and accompanied by another impressive catalog.

At the Fundación MAPFRE exhibition spaces in Madrid, under the curation of the renowned Estrella de Diego, a sense of order and coherence was brought to what had appeared somewhat chaotic at the Pompidou. The show is organized into three major thematic blocks, each with its well-structured subthemes. The first: Surrealisms with Breton near and Surrealisms with Breton far; the second: Dream and Desire; and finally, The Castle of the Surrealists, an evocation of a lost paradise.

This adaptation rigorously explores the importance of creative responses to the movement in countries such as Spain, Belgium, Brazil, Cuba, and Argentina. In addition to the usual suspects—Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Óscar Domínguez, Picasso, or Joan Miró—the curator has included Nicolás de Lekuona, José Alemany, Maud Bonneaud, Ángel Planells, Joan Massanet, Delhy Tejero, and Amparo Segarra. Equally essential is the recognition of what occurred in the Canary Islands, highlighted through the textual contribution of Isidro Hernández, chief curator of the TEA collection, who focuses on the central role of this region and the influence of the exhibition held at the Ateneo de Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1935. Thus, including new focal points and peripheral authors makes this revision one of the most compelling proposals of Madrid’s exhibition season, already positively reviewed by experts such as Fernando Castro Flórez, a leading authority. However, though it does not directly address this project, I would like to point out an issue related to gender questions and the prevailing benevolence that permeates the new decolonial fashion.

Stern, G. Sueño No. 15: Untitled, from the series “Sueños,” photomontages. Buenos Aires, 1949. Silver salts on paper / later print (1996) by Ricardo Sanguinetti, 20.5 × 28.7 cm. Photo: © Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, IVAM. Photo: Juan García Rosell.

First, we might ask why Jean Cocteau was not considered part of the Surrealist group. The reason lies in the fact that Cocteau faced homophobia within the movement for years, mainly due to conflicts with Breton. Likewise, we should remember the intrepid and visionary Leonor Fini, who—although she exhibited and engaged with leading Surrealists between 1930 and 1940—never wished to link her work to the movement. Her themes and language approached the surreal but did not share its conceptual roots. Fini remained independent, above all criticizing Breton as a misogynist.

This assertion is evidenced in Breton’s Manifesto, where female Surrealist artists are called “beautiful and nameless.” The focus on these creators has often centered on their biographies’ sentimental ups and downs and anecdotes about their “mediumistic discoveries” in parallel unconscious worlds. This superficiality also marks media-hyped exhibitions like Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim, whose catalog fails to offer the depth this artist deserves.

Carrington, L. Darvaux, 1950, Oil on canvas, 80 × 65 cm. Private collection © 2025, Estate of Leonora Carrington / VEGAP. Photo: Willem Schalkwijk.

We know that in 1985, American art historian Whitney Chadwick published Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, driven by the urgent need to analyze these productions.

Revealing exhibitions like We Are Fully Free: Women Artists and Surrealism, curated by José Jiménez in 2018 for the Picasso Museum in Málaga, also come to mind. This exhibition recovered figures such as Eileen Agar, Claude Cahun, Leonora Carrington, Germaine Dulac, Leonor Fini, Valentine Hugo, Frida Kahlo, Dora Maar, Maruja Mallo, Lee Miller, Nadja, Meret Oppenheim, Kay Sage, Ángeles Santos, Dorothea Tanning, Toyen, Remedios Varo, and Unica Zürn.

With that spirit in mind, it’s essential to highlight the work of another unclassifiable creator, the British artist and writer Ithell Colquhoun, whose exhibition Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds was on view at Tate St Ives in London until May 5, 2025.

Colquhoun, I. Wooded Valley,1947. Watercolor and ink on paper. 45.7 × 32cm. Tate: Archive. INV. NO: TGA 201913. © Samaritans, © Noise Abatement Society & © Spire Healthcare Photo © Tate, Reserved Rights.